Orville and Wilbur Wright were American brothers who were inventors and aviation pioneers. They are generally acknowledged as conceiving, constructing, and flying the world’s first successful airplane.

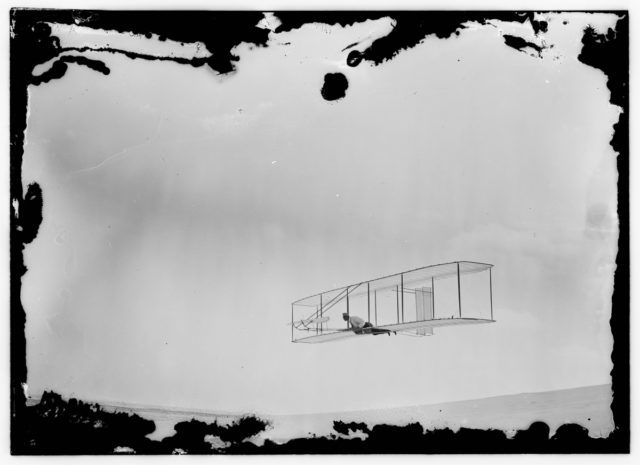

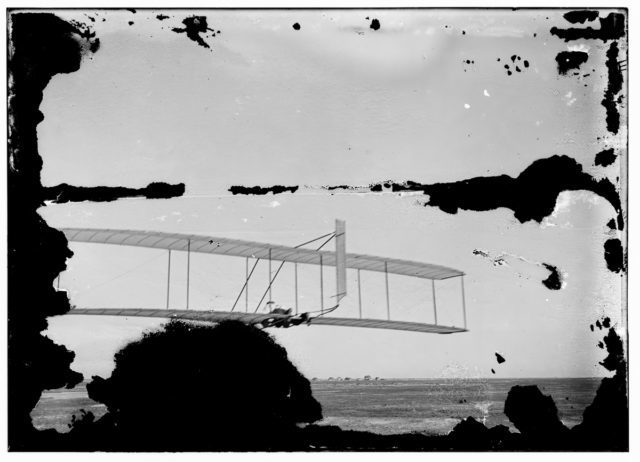

On the 17th of December 1903, just a little ways from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, they made the first coordinated, prolonged flight of a powered craft that was heavier-than-air. In 1904-1905 the brothers advanced their flying apparatus into the first practical fixed-wing aircraft. Although they were not the only ones to build and fly experimental aircraft, the Wright brothers were the first to invent mechanisms that made fixed-wing powered flight achievable.

Otto Lilienthal had made ‘whirling arm’ aerodynamic tests on a few different wing shapes, and the Wrights incorrectly presumed the statistics would pertain to their wings, which were shaped differently. The Wrights undertook a huge measure forward and performed basic wind tunnel tests on 200 wings of many shapes and designs. They followed this with detailed tests on 38 of them. According to biographer Fred Howard, the tests, at the time, were the most critical and prolific flight experiments ever organized in so little time with so scarce equipment and with so little cost.

A significant discovery was the advantage of longer, narrower wings, which meant a larger aspect ratio. To put it in aeronautical terms – wingspan divided by chord – the wing’s front-to-back dimension. These tests proved that such shapes provided much better lift-to-drag relation than the broad wings the brothers had tried up to that point.

The Wrights designed their 1902 glider with this knowledge and a more accurate Smeaton pressure coefficient number. Using another crucial discovery from the wind tunnel testing, they made the airfoil shape flat, which reduced the curvature of the wings. The wings of the 1901 glider had significantly greater curvature, which turned out to be a highly inefficient characteristic the Wrights duplicated directly from Lilienthal. Totally confident in their new wind tunnel outcomes and now creating their designs on their own calculations, the Wrights abandoned Lilienthal’s data.

Being characteristically cautious, the brothers first flew the 1902 glider as an unmanned heavier-than-air craft (a kite), the same as they had done with their two previous editions. The glider produced the expected lift; rewarding the brother’s wind tunnel work. The glider also had a new mechanical component, which the brothers hoped would eliminate problems turning – a fixed, vertical rudder at the rear.

By 1902 they realized that lateral control of a fixed wing aircraft created ‘differential drag force’ at the wingtips. Greater lift at one end of the wing also increased the drag force, which slowed that end of the wing, making the glider swivel or ‘yaw’ so the nose seemed to steer away from the turn. This was also how the tailless glider behaved in 1901.

The enhanced wing design enabled consistently lengthier air time and the rear rudder prevented adverse yaw. It was so effective that it introduced a new problem for a manned craft.

Sometimes, as a pilot was attempting to level off from a turn, the glider failed to respond to correct the lateral control and persisted into a tighter turn. The glider would tip toward the lower wing, which would touch the ground, making the aircraft spin around. The Wright brothers called this ‘well digging’.

Apparently, Orville Wright visualized that the fixed rear rudder resisted the effects of corrective lateral control when making an attempt to level off from a turn. He made an entry in his diary that he studied the idea of a new vertical rudder on the night of October 2. To solve the problem, the brothers decided to make the rear rudder movable. They installed hinges on the rudder and connected it to the pilot’s ‘steering cradle’, so a solitary movement by the pilot simultaneously controlled lateral movement and rudder deflection.

Trial and error tests while gliding proved that the dragging edge of the rudder should be turned in the opposite direction from whichever end of the wings had more drag (and lift) due to warping. The divergent pressure produced by turning the rudder enabled corrective lateral control to consistently restore level flight after a turn or from wind turbulence. Furthermore, when the glider veered into a turn, the rudder pressure prevailed over the effect of the differential drag force and steered the nose of the aircraft in the direction of the turn, thereby, completely eliminating adverse yaw.

In summary, the Wrights discovered the true purpose of the hinged vertical rudder. Its function was not to change the direction of flight (as a rudder does in sailing), but rather, to aim or to correctly bring the aircraft into line during banking turns, when leveling off from turns, and wind turbulence. The actual turn – the change in direction – was done with roll control using wing-warping. The theory remained the same when wing-warping became obsolete as it was replaced by ailerons.

With their new technique, the Wrights achieved a major milestone on the 8th of October 1902; true control in turns for the first time. From the 19th of September to the 24th of October 1902, they attempted between 700 and 1,000 glides, the longest covering 622.5 feet and lasting 26 seconds.

After they made the rudder steerable and completed hundreds of well-managed glides, they were convinced that they were prepared to build a powered flying machine.

From all of the Wright’s data and preparation, the three-axis control flight evolved: forward elevator for pitch (up and down), rear rudder for yaw (side to side), and wing warping for roll (lateral movement). The Wrights applied for their famous patent for a ‘Flying Machine’ on the 23rd of March, 1903, based on their success with their 1902 glider.

Here is another story from us: One SAS soldier took down more planes than several aces combined

Several aviation historians believe that the application of the three-axis flight control system on the 1902 glider was equal to, or even more noteworthy, than the addition of power to the 1903 Flyer. Peter Jakab of the Smithsonian Institute emphasizes that the perfection of the 1902 glider essentially signified the invention of the airplane.