The Oseberg ship is widely renowned and has been called one of the greatest finds to have ever survived the Viking Age.

The Oseberg burial mound contained numerous burial artifacts and two human skeletons, both female. The ship’s entombment into the burial mound dates to 834 AD, but some contents of the ship date from before 800 AD and the ship itself is believed to be older.

The excavation of the ship was conducted in 1904 and 1905 by Swedish archaeologist Gabriel Gustafson and Norwegian archaeologist Haakon Shetelig. The excavation was of great interest to the general public.

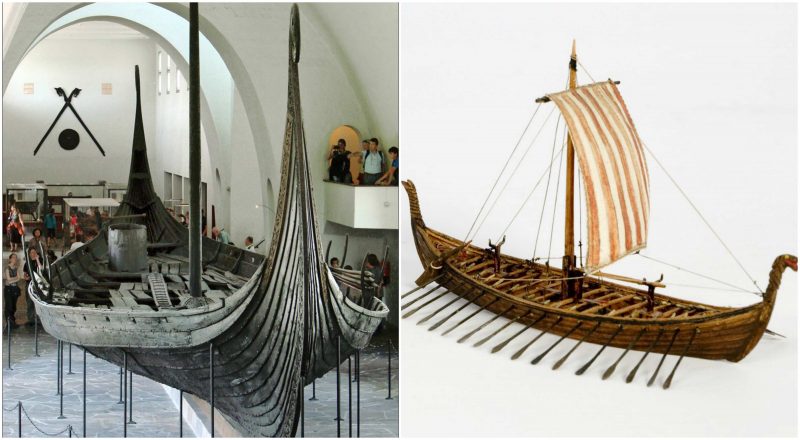

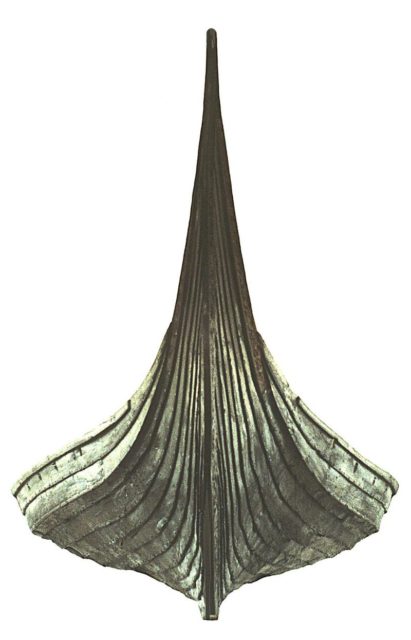

The ship is a ‘clinker built’ smaller version of a Viking longship, made almost entirely of oak. It is 5.10 m wide and 21.58 m long, its mast is between 9 and 10 meters high and with a sail of about 90 m², the ship could achieve speeds of up to 10 knots.

The ship could accommodate 30 people for rowing the ship. Other components included a bailer, a wide steering oar, an iron anchor, and a gangplank. The bow and stern of the ship are lavishly decorated with intricate wood carvings in the distinguishing ‘gripping beast’ motif, also known as the Oseberg style. The ship is rather frail, although it is seaworthy and it is believed to have been used only for coastline journeys.

The design for ocean travel has been shown to be unsuitable on two occasions, during moderate weather, with the twice sinking of a modern replica. The primary reason appears to be the short distance from the waterline to the upper deck, particularly towards the bow where the hollow (concave) sections lack the water displacement necessary when the ship is propelled down the wind, even by the restricted sail capacity.

After the first sinking of the replica, the mast was moved further aft, and the sail area was reduced to prevent the bow from being forced under, but these steps were inadequate to avert a second sinking.

Discussions were held whether to move the original ship to a new proposed museum and a comprehensive study was conducted into the possibility of moving the ship without damaging it. During this process, methodical photo scans and detailed laser scans of both the interior and exterior of the ship were made. A new attempt to build a replica of the Oseberg ship commenced in 2004.

A combined effort of Danish and Norwegian professional shipbuilders, scientists, and volunteers joined in this new challenge with the photo and laser scans made available at no cost to the passionate builders. An important discovery was made during this new attempt. It was discovered that during the first rebuild of the ship a mistake was made in the length of one of the beams and the ship was therefore unintentionally shortened.

Because this fact had not been discovered previously, it is believed this is perhaps the primary reason why the earlier replicas sank – previous attempts at successfully working replicas had failed due to incorrect data. Another new build called Saga Oseberg was started in 2010. Using lumber from Denmark and Norway and employing traditional building techniques from the Viking age, the newest Oseberg ship was completed successfully in early 2012.

On 20 June 2012, the new ship was launched from the Norwegian city of Tønsberg. The ship sailed and maneuvered very well and in March 2014, it headed to open seas under full sail with Færder, Norway as its destination. On the open seas, the Saga Oseberg achieved a speed of 10 knots. The ship performed very well; the construction was a huge success. It proved forever more that the Oseberg ship really could sail, that it actually had sailed, and it was not just a burial chamber on land.

Of the skeletons of the two women found in the grave with the ship, the first suffered badly from arthritis and other illnesses and was probably aged between 60–70 years. The second was originally believed to be aged 25–30 years, but analysis of dental root translucency suggests she was older – aged 50–55.

It is not certain which of the women was the more notable in life or whether one was sacrificed to escort the other in death. The younger of the two had a broken collarbone, which led to the belief that she was a human sacrifice, but closer examination showed that the bone had been healing for several weeks prior to her death.

The lavishness of the burial ceremony and the artifacts found in the grave suggests that this was a burial of very high status. One woman wore an exquisite red wool dress with a luxury twill pattern and a delicate white linen veil in a gauze interlace, while the other wore an unadorned blue wool dress with a wool veil, perhaps exhibiting some categorization in their social status.

Nothing entirely made of silk was worn by either woman, although small silk strips were sewn onto a tunic worn under the red dress.

Batnamn: Osebergsskeppet 800-tal Photo Credit

The tree-ring dating (dendrochronological) analysis of timbers at the grave-site mound dates the burial in the autumn of 834. Although the identity of the high-ranking woman’s is not known, it has been implied that she is Queen Åsa of the Yngling tribe, who was the mother of Halfdan the Black and the grandmother of Harald Fairhair.

A Recent analysis of the women’s skeletons implies that they lived in Agder in Norway, as had Queen Åsa. However, this theory has been challenged, and some think she may have been a völva; a shaman in Norse history. Also found on the ship were also the skeletal remains of three dogs, fourteen horses, and an ox.

The younger woman’s mitochondrial haplogroup – we’ll just call it mtDNA – was categorized as U7, which is West Eurasian, according to Per Holck of Oslo University. Her ancestors probably came to Norway from Iran. However, three succeeding studies failed to confirm this because of two probable reasons – it is likely that the skeletal samples contain little, if any; genuine DNA or excessive handling has contaminated them.

More insight into the two women’s lives has been provided by examining fragments of the skeletons. An inspection of the younger woman’s teeth indicated that she used a metal toothpick, a rare luxury in the 9th century. Another luxury both women had was a diet comprised predominantly of meat, when fish was the staple of most Vikings. However, there was not enough DNA to reveal if they were family or even related, for that matter, for instance, a queen and her daughter.

The gravesite had been disturbed in the distant past, and precious metal artifacts were missing. Nevertheless, a large number of mundane items and artifacts were discovered during the 1904-1905 excavations.

These included a richly carved four-wheel wooden cart, wooden chests, four ornately decorated sleighs, bedposts, and as well as the so-called ‘Buddha bucket’ (Buddha-bøtte), an elaborately decorated brass and enamel ornament of a bucket and handle in the shape of an individual sitting with legs crossed.

The bucket is made from yew wood, bound together with brass strips and the handle is fastened to two human-type figures that are likened to representations of the Buddha in the lotus position, although it is not certain that there is any connection. Probably more relevant is the relationship between the decorated enamel torso and comparable human figures in the Gospel books of the insular art of the British Isles, such as the Book of Durrow.

More ordinary artifacts such as household and agricultural tools were also discovered. Also unearthed were a series of textiles included narrow tapestries, imported silks, and woolen garments. The Oseberg burial site is one of the very few sources of Viking Age textiles, and the wooden cart is the only Viking era cart found completely intact so far. One of the bedposts shows a rare example of the use of what has been dubbed the ‘valknut’ symbol, an Old Norse symbol representing slain warriors.

The preservation of the wooden artifacts is an ongoing issue without a final decision as of yet. Thirteen years after the debate began over the disposition of the ship; Norwegian Minister of Education Kristin Halvorsen stated on 3 May 2011 that the ship will not be moved from Bygdøy.