Time Square’s New Year’s Eve celebration has been regarded as one of the most notable celebrations of the New Year internationally. As the streets of the square close for traffic hours before midnight each 31st of December, the city of New York rushes for the final preparations for its most impressive celebration that culminates in the dropping of the New Year’s balls. And the ball dropping is a story in itself.

Thousands of people gather to see the ball descending some 141 feet in the last minute of the old year, and to announce the birth of the new one. The symbolic act of descending the ball at exactly 11:59 PM, ET has persisted through most of the 20th century and has continued up to the present day. This season, as we are about to welcome 2018, the ball dropping tradition marks its 100th anniversary. Fireworks regularly follow the ball drop, and as of more recent times, also live performances by musicians and other entertainers. But how did it all start and what are the origins of this event?

The first ball drop in New York

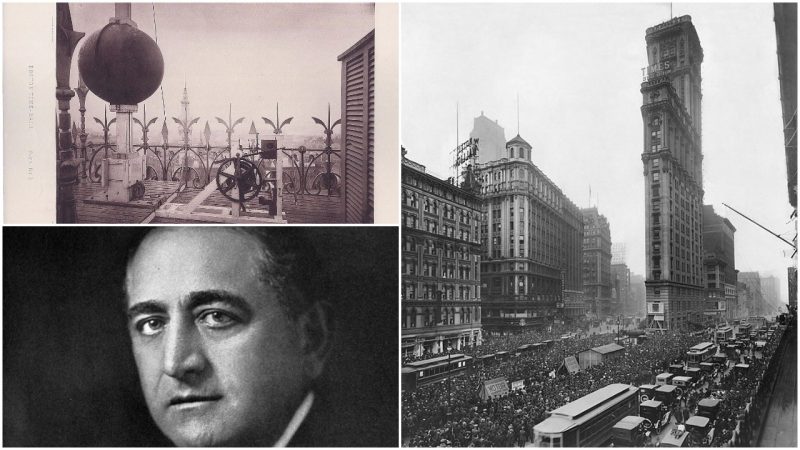

The very first ball drop event in New York took place exactly a century ago, on December 31, 1907, so to welcome in the year 1908. As accounts tell, the event was originally initiated by Adolph Ochs, the then-owner of The New York Times newspaper. Still, the first celebration followed to several previous festivities on New Year’s Eve at Times Square, the first of which was to welcome 1905 and matching Adolph’s wishes to also cherish the moment of opening his newspaper’s brand new headquarters at One Times Square. Perhaps a crowd of 200,000 gathered to welcome 1905, enjoying a show of fireworks as well at the rooftop of the new headquarters.

Setting the New Year’s Eve festivities at Times Square also meant abandoning the traditional location for the Eve, which was previously at Wall Street’s Trinity Church, and where crowds would normally gather to listen to the bells of the church at midnight. However, the festivities hosted by Adolph quickly turned out way more popular.

Regardless of the fact that his events already attracted huge crowds, he still wanted to do something more. So he had eventually hired Artkraft Strauss, a prominent New York designer of the day and the famed creator of the Times Square’s iconic signs. Ochs would ask Strauss to design a time ball this time, that would add to the New Year’s panache, while the idea of having a time ball was originally suggested by Walter F. Palmer, the editor-in-chief of the Times.

It was wood and iron that composed the very first ‘time-ball’ and it shone brightly as it had a hundred light bulbs. It weighed an astonishing 705.5 pounds and measured almost five foot in diameter. It took the efforts of six people to hoist the ball onto the flagpole of the building, and once up there on the rooftop, the ball was set to run an electrical circuit and light up a sign that was to announce the first strike of the New Year. Then the fireworks were to follow.

Despite The New York Times went on to move its headquarters again in 1913, Adolph kept on organizing the ball drop, and it became the new tradition of New York City. It was only in 1942 and 1943 when the time ball did not happen, due to the respective observance of the wartime blackouts.

Time balls were first used for maritime navigation

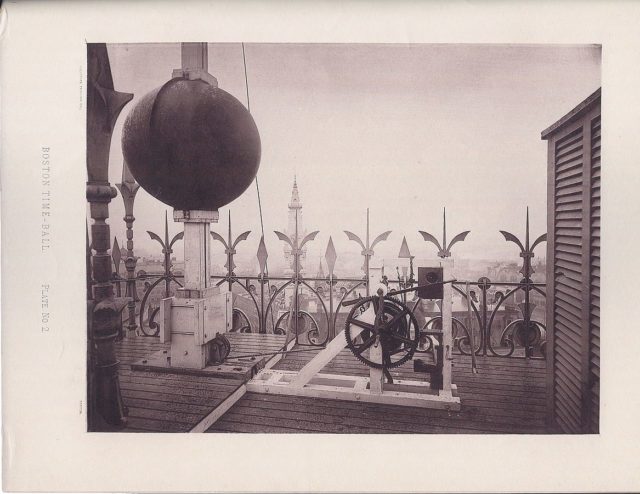

It may surprise you, but before the ball dropping was introduced as a means to announce the New Year at the Times Square celebration, time balls already had a long tradition in maritime navigation. They had a practical use as time-signaling devices.

Time balls were large, usually made of painted wood or metal and were dropped at predetermined time intervals. They were purposed to help navigators at sea, or more exactly, marine chronometers found aboard vessels.

A marine chronometer was a peak technological achievement back in the 18th century, used as a portable time standard. It enabled ships to settle longitudes at sea, employing astronomical navigation, as well as it allowed ships’ crew to tell the time accurately over long-distance journeys across the world seas. It was a much-needed gadget for navigation in times when there weren’t any means of electronic communication devices.

Originally, time ball stations were situated at observatories, and they would adjust clocks thanks to transit measurements of the positions of stars as well as that of the sun. The first such ball purposed to help maritime navigation popped up on the south coast of England in 1829, at Portsmouth. It got there thanks to its inventor, and then-captain of the UK’s Royal Navy, Robert Wauchope. Once electric telegraph was introduced around the mid-19th-century, time balls started to operate more remotely.

Along with new technological advancements throughout the 20th century, time balls have been replaced by electric time signals. Sometimes, balls have, however, remained functional as historical tourist attractions, or in the case of the Times Square New Year’s Eve celebrations, as an inseparable part of the event.

Since 2009, the current ball used for the New Year’s celebrations is displayed atop the One Times Square year-round, while a smaller version of it is on display at Times Square’s visitor center.