For centuries, the Parthenon temple, originally built in honor of the Greek goddess of wisdom and war, Athena, has been the most memorable sight on the skyline of the Greek capital. Perched atop the Acropolis hill, the Parthenon, aside from being one of the most popular places of interest for those visiting Athens, has influenced architects across the globe. An example is Carl Gotthard Langhans, who took his inspiration for the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin from the Greek site.

Over its extensive history, the Parthenon has witnessed virtually everything, and some of it unfortunate. Such as the time during the 1910s, when the British Ambassador to Constantinople, Lord Thomas Elgin, commissioned a few of his agents to pilfer artifacts from the structure. Consequently, dozens of invaluable antique sculptures that had adorned the Parthenon ever since the 5th century BC were transferred to London.

Collecting the Greek treasures created a massive scandal. Debates over whether the deeds of Elgin were legal or not heated up even before the cargo of treasures reached London. According to a BBC report, there were “17 life-size marble figures from its gable end” as well as “15 of the 92 metopes, or sculpted panels, originally displayed high up above its columns” taken from the Parthenon.

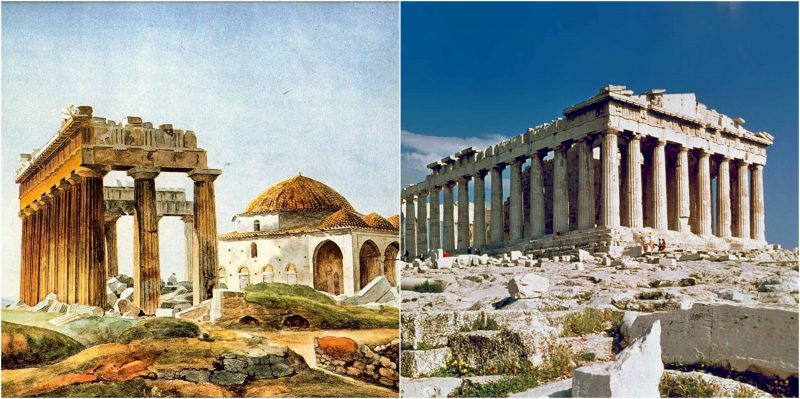

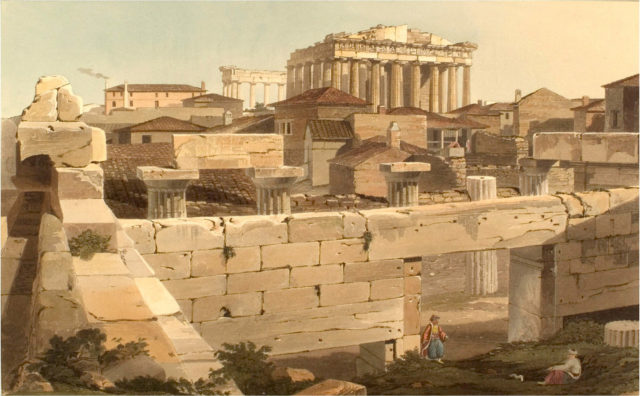

But truth be told, at this point the Parthenon already looked diminished, quite different from what we find today. Ever since 432 BC, when the Parthenon was erected, it has been in continual usage. Principally intended as a Greek temple, under the Byzantine Empire the Parthenon spent a millennium as a Christian church. Then, as of the 15th century, when the Ottomans took control of Greece, it was converted to a mosque.

Historians are slightly baffled over when the Ottomans made this radical change. The shrewdest guess is that it happened under the orders of Mehmed the Conqueror, perhaps the most powerful sultan of all who reigned over Constantinople. He extended the borders of the Ottoman Empire to the Balkans, and his armies captured Athens in 1458. Allegedly, changing the Parthenon into a mosque came as a punishment to the Athenians for attempting a plot against the Ottoman reign.

Other historical accounts suggest that the structure had undergone fewer changes by the mid 17th century than undertaken by Christians when they took over. When the Parthenon was used as a mosque, the Ottomans would conduct their religious customs and prayers beneath various Christian motifs and paintings, included a vast mosaic of the Virgin Mary.

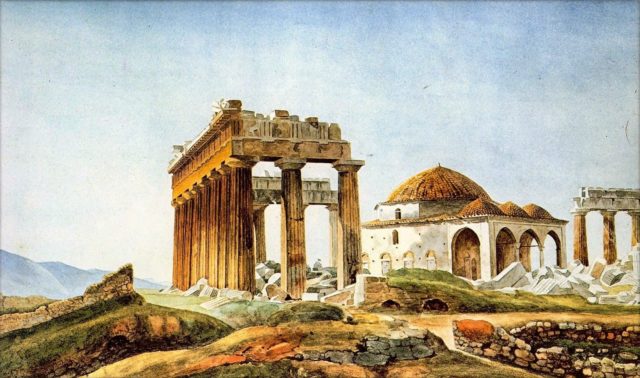

Some additions they made featured paintings such as the Last Judgment, which incorporated an array of pagan-like, Christian, as well as Muslim religious figures. The face of the hill changed in 1687, when a deafening explosion destroyed the mosque. After which, apparently, a second mosque was built.

Author Jenifer Neils describes the mosques within the boundaries of the Parthenon in her book The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present. The second mosque “was small and simple, square in plan, set at an angle to the older remains with a portico facing northwest.”

Neils also writes that in contrast to the first mosque, the second one was made in a more typical Ottoman fashion, having “its interior covered by a dome raised above an octagonal transition, with small domical vaults over the three-bayed porch.”

Despite being described as small, according to a British traveler who saw the site somewhere around the mid 17th-century, the hill had “the finest mosque in the world.” Nevertheless, this new structure was constructed out of reused stones, hence it was not of the finest quality.

The edifice would remain there until somewhere during the 1820s, when the Acropolis was the subject of several sieges throughout the Greek War of Independence. No significant renovations of the Parthenon took place in the next decades, at least not until the 1890s. Then, under the watch of Nikolaos Balanos, the first long-term reconstruction effort was launched, which according to many modern-day preservationists is when the site underwent even greater damage.

Balanos re-erected several columns that had suffered damage in the 1687 explosion and commissioned inserting casts of several sculptures that were previously collected by Lord Elgin’s agents. He also worked on strengthening the interior walls of the structure, but the methods he used would only cause more problems in the long term, jeopardizing the integrity of the entire Parthenon by adding iron clamps to hold the handiwork together.

Balanos clamps eroded over the years, and more importantly they did not allow for the natural expansion and contraction of the stone, which had caused further damage to numerous fracturing pieces of the structure. As of 1975, preservationists were taking the reconstruction effort way more seriously. Now under the watch of architect Manolis Korres, a costly effort commenced, costing more than $90 million. Finally, the Parthenon started to take the shape it shows today, while some of its original components and artifacts would be safely stored at the newly opened Acropolis Museum.