Located in New Orleans on North Rampart Street between St. Anne and St Peter Streets, in the Tremé neighborhood, Congo Square holds great significance for both the city of New Orleans and the history of its African American people.

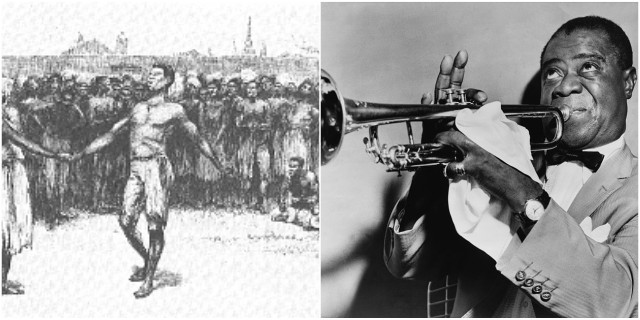

Before the nineteenth century, during the French and Spanish colonial era, Congo Square was one of many informal meeting places where enslaved Africans and free people of color would gather on Sunday afternoons to socialize, sing, dance and play music.

This tradition continued when the United States purchased Louisiana from France at the beginning of the nineteenth century. However, when in 1817 Augustin de Macarty, the mayor of New Orleans designated Congo Square as the only acceptable place where slaves were allowed to gather, Congo Square became known for the musical celebrations held on Sundays and attracted visitors from all over the United States.

Most slaves in New Orleans were from Africa, but there were also people from the Carribean, Latin America, France, Spain, and many other countries. New Orleans was always a mixture of cultures, and that is what makes New Orleans so special. They all influenced the culture, the architecture and of course the music of New Orleans making it the birthplace of jazz.

Musicians from different countries would bring with them the instruments of their culture to the Sunday gatherings in Congo Square. Benjamin Latrobe, the noted architect, witnessed one of these collective dances on February 21, 1819, and wrote:

“An elderly black man sits astride a large cylindrical drum. Using his fingers and the edge of his hand, he jabs repeatedly at the drum head — which is around a foot in diameter and probably made from an animal skin — evoking a throbbing pulsation with rapid, sharp strokes. A second drummer, holding his instrument between his knees, joins in, playing with the same staccato attack. A third black man, seated on the ground, plucks at a string instrument, the body of which is roughly fashioned from a calabash. Another calabash has been made into a drum, and a woman beats at it with two short sticks. One voice, then other voices join in. A dance of seeming contradictions accompanies this musical give-and-take, a moving hieroglyph that appears, on the one hand, informal and spontaneous yet, on closer inspection, ritualized and precise. It is a dance of massive proportions.

A dense crowd of dark bodies forms into circular groups – perhaps five or six hundred individuals moving in time to the pulsations of the music, some swaying gently, others aggressively stomping their feet. A number of women in the group begin chanting.”

When the American Civil War ended, there was an attempt by white city leaders to suppress the gatherings. They even renamed the square to “Beauregard Square,” after former Confederate General, but locals still called it Congo Square. The traditional name was restored in 2011 by the New Orleans City Council.

The rhythms and variations played in Congo Square sowed the seeds of jazz and Congo Square is considered to be a symbol of the African contributions to the origins of jazz. Musicians such as Louis Armstrong, Sydney Bechet, Jelly Roll Morton, and Mahaila Jackson spread the music of New Orleans throughout the United States and later throughout the world.

In 1970 Congo Square became the site of the city’s first Jazz and Heritage Festival, known as Jazz Fest. The festival became very popular and as attendance grew it had to be moved to another part of the city.

Congo Square remains a place where many celebrations and events are held every year. On January 28, 1993, Congo Square was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.