The Normans, from the Old Norse for ‘north men,’ were the descendants of indigenous Scandinavian seafaring pirates and traders called Vikings, who colonized the northwestern part of France in the early 9th century AD.

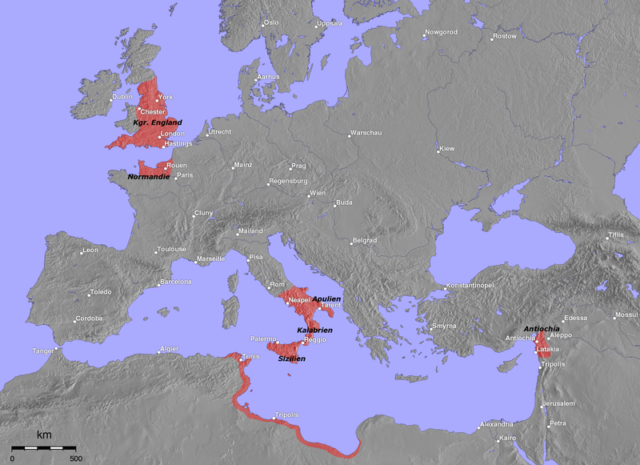

They ruled the region known today as Normandy until the midpoint of the 13th century. The most illustrious of the Normans, William the Conqueror, invaded England in 1066. William vanquished the resident Anglo-Saxons; after William the Conqueror, several kings of England, including Richard the Lionheart, Henry I, and Henry II were of Norman blood and ruled both England and Normandy.

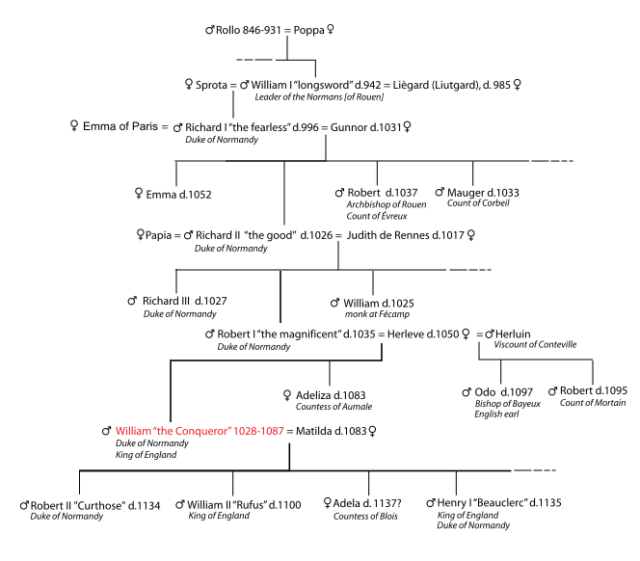

Following is a list of the rulers of Normandy, some of whom, in addition to ruling Normandy, also reigned over England.

Rollo, the Walker, 860-932, ruled the Norman duchy from 911-928, he married Gisla, the daughter of Charles the Simple.

William Longsword reigned from 928-942.

Richard I, the Fearless, born 933, ruled Normandy from 942-996, married Hugh the Great’s daughter, Emma.

Richard II, The Good, reigned over Normandy from 996-1026, married Judith.

Richard III ruled Normandy from 1026-1027.

Robert I, The Magnificent, or The Devil, reigned Normandy 1027-1035. He was Richard III’s brother.

William the Conquerer, 1027-1087, ruler from 1035-1087, also King of England after 1066, married Matilda of Flanders.

Robert II, Curthose, reigned over both regions from 1087-1106.

Henry I, Beauclerc, born 1068, King from 1100-1135.

Henry II, born 1133, reigned both regions from 1154-1189.

Richard the Lionheart ruled Normandy and England 1189-1216.

King John, John Lackland, reigned from 1199-1216, eventually lost Normandy to King Philip II of France.

The Vikings arrived from Denmark and began raiding in the territory today known as France around 830AD. They found that the current rulers were in the midst of an ongoing civil war. Because the current weakness of the Carolingian empire made it an attractive target, there were several groups, including the Vikings, who were prepared to strike and conquer land and people.

The Vikings used identical strategies in France as they did in England – plundering the monasteries, demolishing markets and towns, imposing taxes or ‘Danegeld’ on the people they conquered, and killing the bishops, which disrupted religious life and caused a severe decline in literacy.

Obtaining the direct involvement of France’s rulers, the Vikings became permanent settlers, although many of the land grants were merely an acknowledgment of actual Viking control of the region.

Temporary villages were first founded along the coastline of the North Sea; arising from a succession of royal grants in Frisia to the Vikings from Denmark. The first of these royal land grants was bestowed to Harald Klak in 826 when Louis the Pious granted him the county of Rustringen to use as a refuge. Succeeding rulers did the same with subsequent Viking leaders, usually with the aim of placing one Viking in a position to defend the Frisian coast against other possible invaders. In 851, a Viking army spent the winter on the Seine river and while there, joined forces with Pippin II, and the Bretons, who were the primary enemies of the king.

The principality of Normandy was established by Rollo (Hrolfr) the Walker, a leader of the Vikings in the early 10th century. The Carolingian king, Charles the Bald, relinquished land to Rollo in 911, including the lower Seine valley, with the Treaty of St. Clair sur Epte. This was extended to include ‘the land of the Bretons,’ by 933 AD, and became what is known today as Normandy when the French King Ralph granted the land to Rollo’s son, William Longsword.

The Viking high court, based in Rouen, was always a little unstable, but Rollo and his son William Longsword did their best to bolster the duchy by marrying into the elite families of the Franks. There were several crises in the Norman duchy in the 940s and 960s, particularly upon the death of William Longsword in 942. When he died, William’s son Richard I was only 9 or 10. There were conflicts among the Normans, in particular between the Christian and the pagan groups. Rouen remained as an underling to the Frankish kings until the Norman War of 960-966, when Richard I fought against Theobald the Trickster.

Richard I defeated Theobald, and new conquerors pillaged his lands. It was the point in history when ‘Normans and Normandy’ became a formidable constitutional influence in Europe.

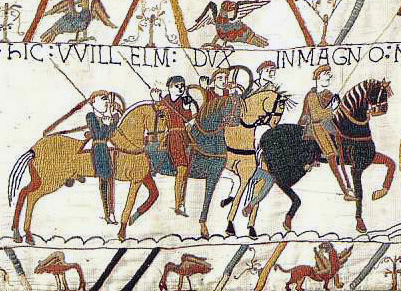

Succeeding to the duchy throne in 1035 was William, the 7th Duke of Normandy, the son of Robert I. William married Matilda of Flanders, who was his cousin and to appease the church for doing so, he built two monasteries and a castle in Caen. By 1060, he was building a new power base in Lower Normandy, where he began assembling supplies and manpower for the Norman Conquest of England.

Archaeological proof of the Viking existence in France is unusually slight. Their villages were mainly fortified hamlets, consisting of elevated earthwork-protected sites called mottes and an enclosed bailey surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. These hamlets/villages were not that different from other such villages in France and England at that time.

The reason for the lack of proof of precise Viking existence could be that the earliest Normans tried to fit into the dominant Frankish society. But that didn’t work out too well and in 960, Rollo’s grandson Richard I promoted the notion of Norman ethnicity, in part to petition the kinship of the new allies appearing from Scandinavia.

But that cultural ethnicity was mostly limited to kinship formations and place names, not materialistic culture and by the end of the 10th century, the Vikings and their culture had virtually integrated into that of medieval Europe, About Education reported.

The majority of what we know today of the early Dukes of Normandy comes from Dudo of St. Quentin, a historian whose patrons included Richard I and Richard II. He portrayed an ominous representation of Normandy in his best-known work ‘De moribus et actis primorum normanniae ducum,’ written between 994-1015.

Dudo’s writings were the foundation for future Norman historians, including Robert of Torigni, William of Poitiers (Gesta Willelmi), Orderic Vitalis, and William of Jumièges (Gesta Normannorum Ducum). Other existing texts include the Carmen de Hastingae Proelio and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.