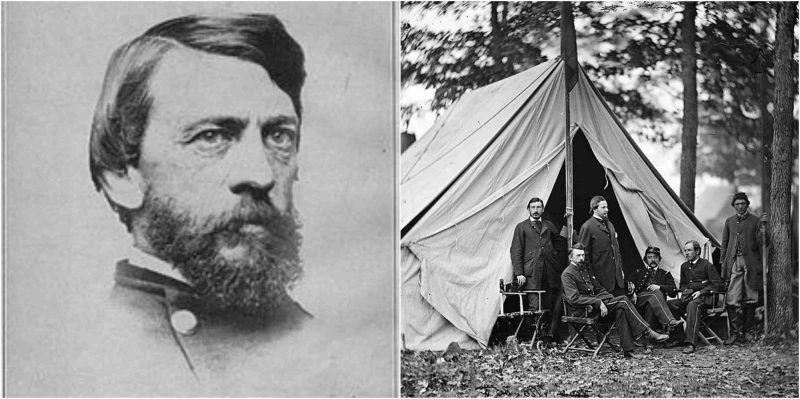

Jonathan Letterman is one of the unsung heroes of the American Civil War. The work that he did to organise for the collection and treatment of the wounded revolutionized battlefield medicine and saved the lives of thousands of young men.

Jonathan Letterman was born on 11 December 1824 in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. He was the son of a famous local surgeon. He was tutored at home and then attended Jefferson College, Pennsylvania, from where he graduated in 1845. He then went on to study medicine at the Jefferson Medical College, graduating with a medical degree four years later.

He immediately applied to join the Army as a surgeon and on acceptance he was stationed with several expeditions, most of which were against Native American tribes. Early in the 1850s, he served in Florida, followed by a move to Minnesota. In 1854, he found himself in Kansas and New Mexico. Following this he was stationed in California and in 1861, with the outbreak of the Civil War, he returned to the east.

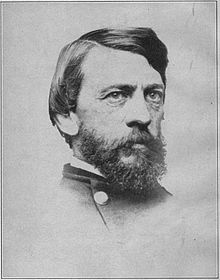

In May 1862, Letterman was appointed as Medical Director to the Department of West Virginia and shortly thereafter he was appointed as Medical Director to the Army of the Potomac. When he took over his duties for the Army of the Potomac, he found the medical facilities in an appalling state. The first item of business was to ensure that all the men received fresh fruit and vegetables, which stopped the scurvy from which they were suffering in its tracks.

Letterman and his associates were dealing with battlefield casualties, the scale of which had never been seen before in the US. The carnage they were witnessing was caused by vastly improved weapons wielded by men forced to carry out antiquated military tactics. Generals forced their men into head-on assaults similar to those used in the Napoleonic Wars and when faced with vastly different weapons the rank and file fell in incredible numbers. Units lost up to a third of their men when forced into a frontal assault.

The wounds that Letterman and the other doctors faced were largely gunshot and cannon wounds. The Springfield musket fired a soft lead ball that tore fist-sized holed in flesh and pulverised bones. Canister and grapeshot fired from cannons would split open, flinging iron pellets at the advancing troops like some kind of giant shotgun.

The Army medical corps were sadly understaffed and under-supplied and were no match for the streams of wounded carried from the battlefields. This situation meant that the Army relied on physicians who were poorly trained and mostly inept, following outdated procedures taught at unregulated schools. Most of these doctors had never treated gunshot wounds or carried out any kind of surgery and now they were faced with the most horrendous of wounds. The only saving grace was that chloroform, morphine, and opium were available to treat pain.

Prior to Letterman taking over, any wound to the head, chest, or abdomen was considered fatal and left untreated except for the supply of morphine. Musket balls caused horrendous wounds to arms and legs and the most common procedure carried out in field hospitals was the amputation of limbs.

A field hospital resembled a scene from Dante’s Inferno, with blood everywhere, piles of amputated limbs, and the screams of the wounded all accompanied by the boom of the cannons, the crash of muskets, and horses shrieking. These poorly trained and under-supplied physicians, nicknamed ‘sawbones’ by the soldiers, did their best in unimaginable conditions. This was a situation Letterman was determined to remedy.

Added to this devil’s brew was the fact that there was no understanding of the link between bacteria and infection. The physicians used the same saw over and over again, leading to all kinds of post-operation complications. Gangrene, tetanus, and blood poisoning were common and accounted for untold numbers of deaths.

Not only did the wounded soldier have to face the horrors of the field hospital but it was not even certain that he would get there in the first place. At the Battle of Second Manassas in August 1862, over 22,000 men were wounded; strewn across the battlefield, it took over a week for the Union soldiers to get the help they needed.

This was the level of inefficiency that Letterman inherited. At the Battle of Antietam at Sharpsburg, two weeks after putting Letterman’s system into place, 12,000 injured Union soldiers were cleared from the battlefield within 24 hours. This was a remarkable turnaround.

Letterman realized that strong organization was required to ensure that battlefield injuries were treated quickly and efficiently, and that by doing this the soldiers had the best chance of survival.

He instituted a plan whereby wagons would be used as ambulances and teams of stretcher-bearers would collect the wounded from the battlefield and transport them to the waiting ambulances, which would then move the injured to a battlefield first-aid station.

His procedures called for the battlefield first-aid station to undertake first-aid, while mobile field hospitals would undertake basic surgery and any emergency procedures. General hospitals further afield would be used for post-operative care. Supporting these three stages of care would be a dependable supply route that ensured medical supplies reached the battlefield stations and field hospitals in good time.

Having proved their value at the Battle of Antietam, Letterman’s procedures faced their biggest test at the three-day long Battle of Gettysburg at the beginning of July 1863. The casualty list for the Union soldiers amounted to an astronomical 23,000 casualties but Letterman’s medical corps took to the field with 1,000 horse-drawn ambulance wagons accompanied by 3,000 drivers and stretcher-bearers. Within 24 hours, the last of the Union wounded were recovered and sent for treatment.

Six months later, Letterman suddenly resigned his commission and broke all contact with the Army. Whilst Letterman and the Army hierarchy may not have seen eye to eye politically, the army did recognize the fantastic job done to organize the Medical Corps. They retained his ideas and in March 1864 the Army ensured that his procedures were instituted across the military.

Letterman moved to San Francisco, where he practised as a doctor and also served as the coroner. He also wrote his memoirs which were published in 1866 under the title of Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac.

Jonathan Letterman died aged 48 on 15 March 1872, and is now interred at Arlington Cemetery. The Army hospital in San Francisco was named in his honor.

Jonathan Letterman may not have been the world’s best doctor but his organizational skills brought medical care to thousands of young men that may never have had the opportunity to be cared for on the battlefield. His system of care has stood the test of time and is still in use today, a testament to the inscription on his headstone, which reads “Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, June 23, 1862, to December 30, 1863, who brought order and efficiency into the Medical Service and who was the originator of modern methods of medical organization in armies.”