Ancient stone coffins called sarcophagi have been used throughout history, and not only by Egyptians entombing their Pharaohs. Sarcophagi were used in the Hellenistic period and in the Roman Empire, and their use continued into the Christian era.

These heavily carved stone tombs sometimes carried the hopes and dreams of the family in pictorial form and reflected on religious ideas of the times.

8. A Musical Child Star

The coffin of seven-year-old Tjayasetimu was purchased by the British Museum in 1888. She was known to be a member of the royal choir in Egypt at the time of her death. She stood just four feet tall and was buried in a manner befitting royalty – wrapped in painted bandages, with her face covered with a veil and a golden mask.

It is unknown for sure how she died, but a rapid illness like cholera was most likely. Researchers state that she must have had a hasty death as the coffin was too big for her. Paintings on the coffin revealed that she was a “singer of the interior”, which tells experts she had an elite role in the choir of the Temple of Amun.

7. Man-eating coffins

A body in a sarcophagus takes approximately 50 to 200 years to decompose. However, in the ones made in the ancient Turkish city of Assos, it only takes about 40 days. The coffins from here are made from andesite stone, and scientists are still not sure if the stone itself is the cause of the rapid decomposition.

The Assos necropolis dates back to the seventh century BC, and the first sarcophagi appear two centuries later. Previous burials were simple burials with flat covers with the name of the deceased inscribed upon them.

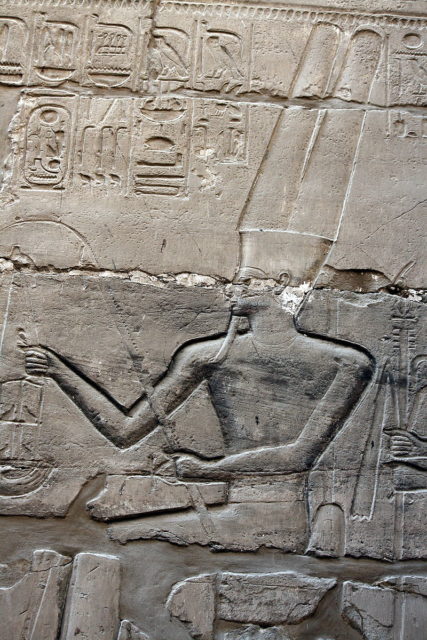

6. Mysterious hieroglyphics

In 2015, the sarcophagus of a high priest of Amun Ra was discovered by archaeologists. The coffin dates from between 943 and 716 BC and is covered in mysterious hieroglyphics. It was a wooden coffin covered in plaster and was discovered in the tomb of Amenhotep-Huy, the vizier of Nubia during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III. The images on the sarcophagus depict him wearing flowers and ribbons, a wig, and a ceremonial beard.

Strangely, his coffin actually dates from the 22nd Dynasty and not from Pharaoh Amenhotep III’s reign. The tomb also contains his Steele of Revealing, which is a funerary tablet showing the deceased making offerings in the traditional garb of a high priest of Amun-Ra.

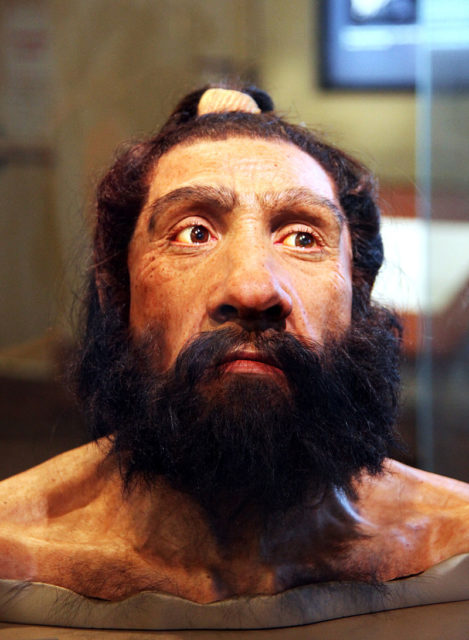

5. Ancient human and Neanderthal fingerprints

In 2005, fingerprints were discovered on an ancient 3,000-year-old sarcophagus lid; experts believe they came from a craftsman who had touched the lid prior to the varnish having dried. The coffin itself is dated to 923 BC and held the remains of an Egyptian priest called Nespawershefyt. Fingerprints have been found before, and the oldest of these have been dated back to 1300 BC. They were found in a loaf of bread preserved in a tomb from Thebes.

The oldest human fingerprints were known to be from a child 26,000 years ago on a ceramic statuette found in the Czech Republic. Neanderthal prints have been found on a weapon-making tool in Germany and these date back over 80,000 years.

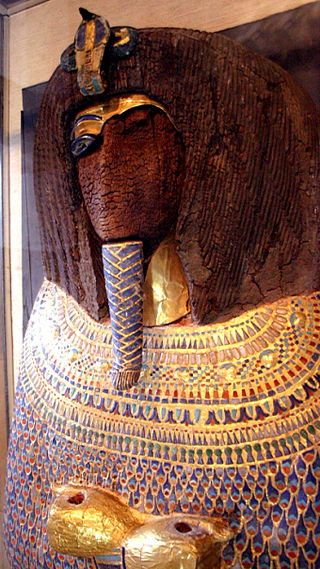

4. Mystery Sarcophagus in the Valley of the Kings

In the ancient graveyard that is Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, an unidentifiable sarcophagus was found in Tomb KV55.

The coffin had been opened and the remains disturbed, with the decorative face mask removed and the name of the occupant chiselled away.

Four canopic jars, a gilded shrine, and furniture were found with the single sarcophagus. The four canopic jars are empty except for effigies of women. No one knows who was in the tomb, but theories are that it could be Queen Tiye or King Smenkhkare – the strongest theory of all is that it was Pharoah Akhenaten. However, unless more evidence comes to light, the identity of the missing body will forever remain a mystery.

3. International scandal and fight over discovery

In 1887, a sarcophagus was discovered containing the remains of Tabnit, a priest of Astarte and the ruler of Sidon. When the lid was removed, the workers found human remains floating in an oily brown liquid which had preserved him perfectly. Unfortunately, the workers tipped this out, and the remains began to decay. The discovery of this and other sarcophagi caused an international incident when the British museum rushed to take the remains away.

Tabnit now rests in Istanbul with his sarcophagus, but only his bones remain. It was discovered during an autopsy that he had died from smallpox when he was approximately 50 years old. Across his coffin is a short hybrid script that blends hieroglyphics and Phoenician writing. It shows the connections that Egypt had with its neighbors and its influence on language.

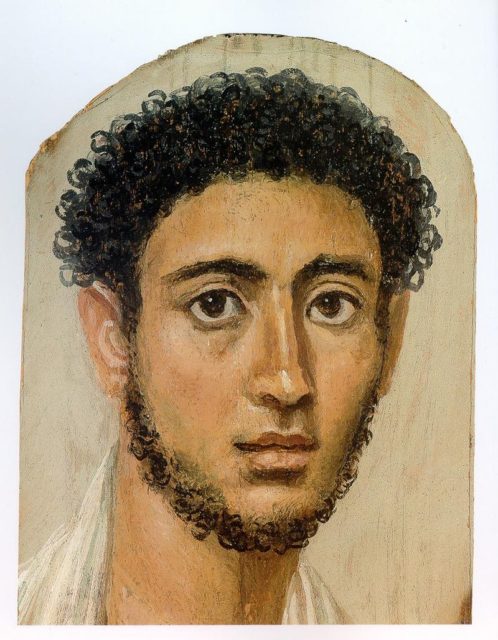

2. Roman Mystery Mummy Portraits

Almost 900 mummy portraits have been found up to today. They were very popular for about 200 years when the Romans occupied Egypt in the first century AD. These paintings were painted on wooden boards and affixed to sarcophagi; the portraits are so realistic that they have been used to identify family members from the likenesses alone. Most of them have been discovered at the acropolis of Faiyum. One of the portraits has been puzzling researchers for quite a while, as it became separated from its sarcophagus over time. The man in it is described as Byzantine with dark eyes and curly hair. They are hoping that by analyzing the pigments used to paint the picture, they will be ale to unravel the mystery of his identity.

1. Delicate Etruscan Sarcophagus Found

In 2015, an Italian farmer in Perugia unearthed a tomb when plowing his fields. Inside, the archaeologists found two sarcophagi which have shed light on the ancient Etruscan civilization. One of the coffins was made of alabaster and marble and contains a male skeleton.

On the outside, there is a lengthy inscription, which states that the deceased’s name is “Lars”. The second coffin was a lot more fragile, made only from painted plaster, and it had already been broken at some point in the past. Not much is known about the occupant, as only a few fragments remain.

The Etruscans lived in Italy near Tuscany between 900 and 500 BC. Artifacts from their culture are very rare and not much is known about these people, even though they introduced writing, winemaking, and roadbuilding to most of Europe.

It is hoped that additional burial sites will be found over time to discover more about these people.