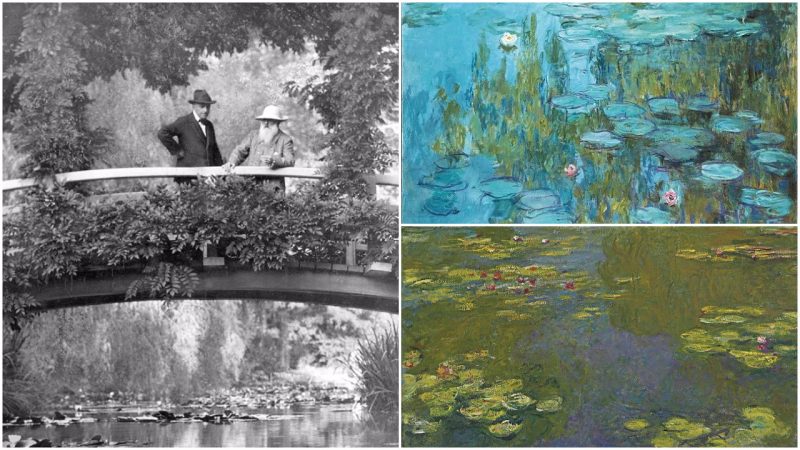

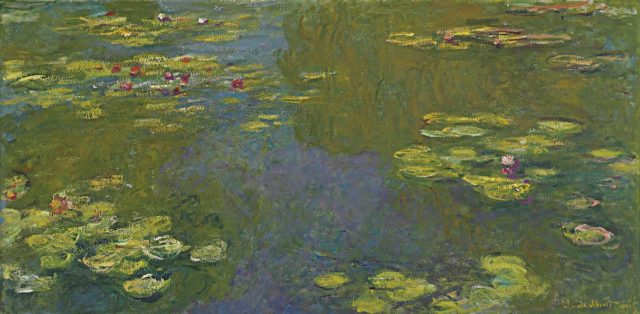

The famous painter Claude Monet, the founder of French Impressionist painting, was first diagnosed with nuclear cataracts in both eyes, in Paris during 1912. He was aged 72 at this period, but he already had experienced changes in the way he perceived colors since the age of 65.

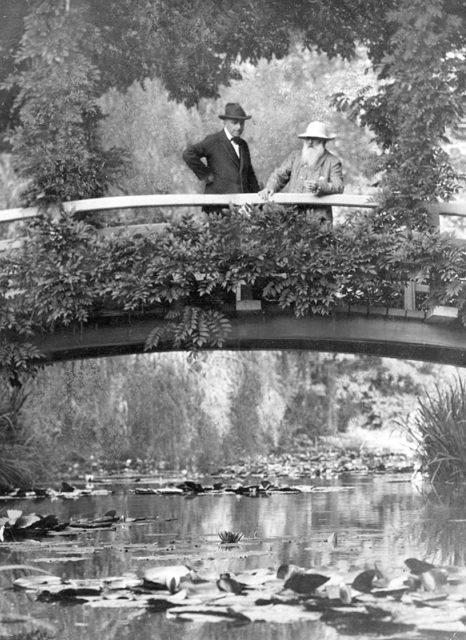

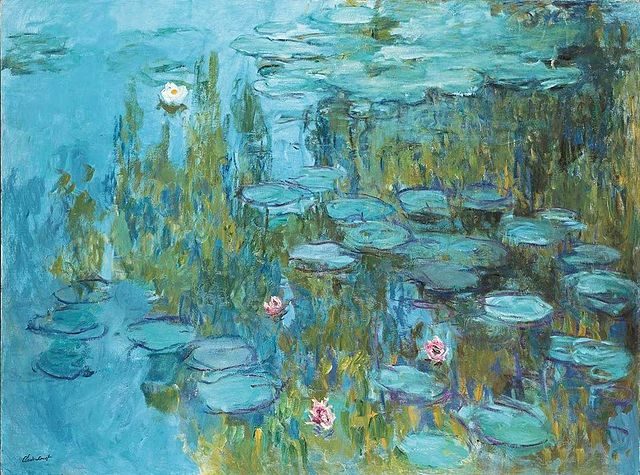

The cataract meant that the painter could no longer see the colors with the same intensity; his whites and greens and blues slowly transformed into muddier, yellowish, and more purple tones. Some of his paintings of water lilies and willows, completed in the period between 1918 and 1922, perfectly manifest that. The sense of atmosphere and light emblematic in his earlier works also disappeared and were replaced by larger brush strokes, frequent absence of light blues, and some obscure coloration.

As the painter was aging and his sight was getting him into more troubles, he also pushed some extra efforts to keep his palette well in order and pay attention to the paint labels. In 1922 he wrote a letter to one of his friends, saying: “To think I was getting on so well, more absorbed than I’ve ever been and expecting to achieve something, but I was forced to change my tune and give up a lot of promising beginnings and abandon the rest; and on top of that, my poor eyesight makes me see everything in a complete fog. It’s very beautiful all the same, and it’s this which I’d love to have been able to convey. All in all, I am very unhappy”.

In 1923, Monet underwent two operations to remove the progressing eye disease. His left eye was closed by dense yellow cataract, which was why he could not see violets and blues, with the other eye, he perceived the same colors clearly.

Monet was skeptical in undertaking the surgeries as he was aware of the effects on his contemporary, the impressionist Mary Cassatt. Nevertheless, in January he operated his right eye. At first, the painter was very disappointed; he thought that resting was only a loss of time at the cost of his art.

In depression, he also tried to rip off the bandages. His frustrations are expressed in a letter which he sent to doctor Coutela who had performed the surgery: “That’s the greatest blow I could have had and it makes me sorry that I ever decided to go ahead with that fatal operation. Excuse me for being so frank and allow me to say that I think it’s criminal to have placed me in such a predicament”.

Later on, the doctor provided Monet with spectacles specialized for cataracts and Monet’s vision corrected, but the painter still found it difficult to adjust to the new lenses. He kept on complaining that he sees distorted shapes and exaggerated colors which he described as “quite terrifying.”

His art was changing, and he would write in another of his letters that, “in the end, I was forced to recognize that I was spoiling them [the paintings], that I was no longer capable of doing anything good. So I destroyed several of my panels. Now I’m almost blind, and I have to abandon work altogether. It’s hard, but that’s the way it is: a sad end despite my good health!”

Some individuals have reported that after the removal of their congenital cataract(which is the clouding of the eye’s lens that blocks light from entering the eyes and focusing clearly), they perceive ultraviolet light. The UV light, which is whitish blue or whitish-violet, remains invisible to those with lens.

Claude Monet’s surgery might have actually allowed him to see these UV lights, and possibly, that was the reason why his paintings differentiated after the medical treatment.