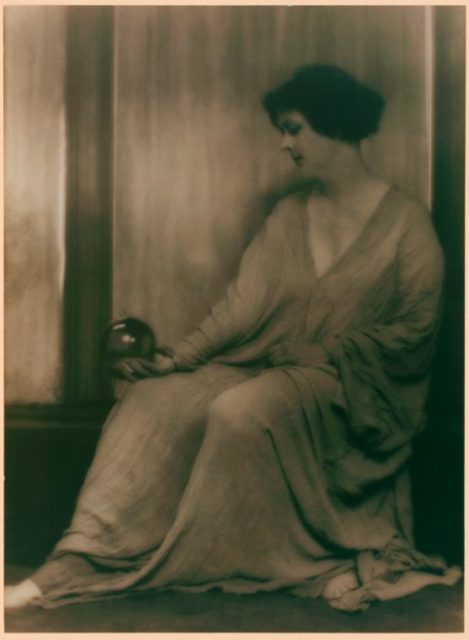

Isadora Duncan was a dancer who was born in 1877 or 1878, in San Francisco. What distinguishes Isadora from all her other contemporaries is that her dancing didn’t adhere to a form, to rules, or rigid ballet techniques. She had a completely different and pioneering philosophy towards dance.

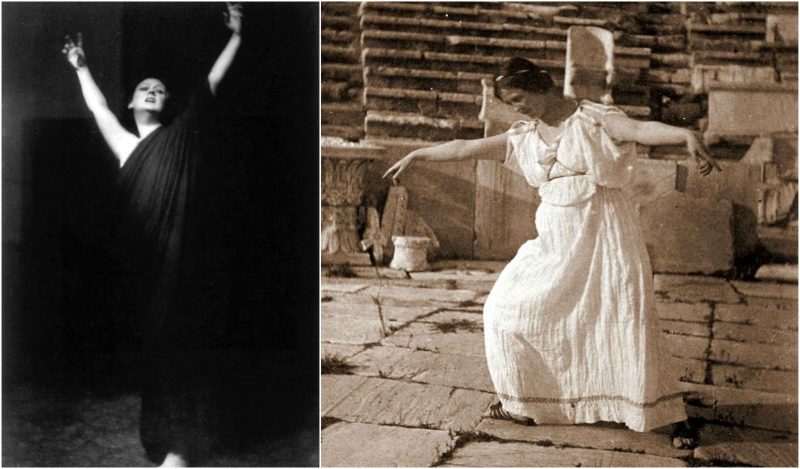

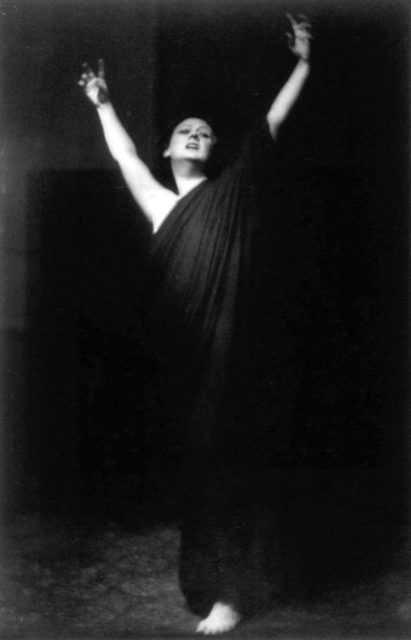

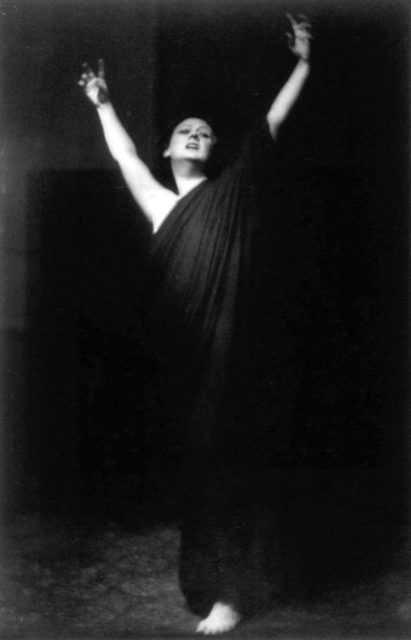

She perceived dance as a natural movement of the body and a medium for the expression of the human spirit. Isadora was deeply moved and inspired by ancient Greek art, which she combined with her American sense of freedom. She is considered the creator of modern dance.

Duncan’s parents divorced when she was just an infant, and she lived with her mother and three other siblings in extremely poor conditions. The children, who were all dancers, didn’t have any other choice but to contribute to their household income by giving dancing lessons to the other kids in the neighborhood. Isadora continued with this throughout her teenage years. She loved dancing, and she always improvised and experimented with her moves. She traveled to Chicago and became part of the Augustin Daly’s theater company. From there, Isadora moved to New York City, where, unfortunately, the stage wasn’t ready for her unique movements.

Feeling disappointed and unappreciated, Isadora left America and moved to London in 1898. In London, she danced in wealthy peoples’ drawing rooms, while she was drawing her inspiration from the Greek art in the British Museum. Her earnings were sufficient for renting a studio where she could create “magic” for the stage. After London, Isadora traveled to Paris, drawing more inspiration from the Louvre.

In 1902, Isadora was invited by Loie Fuller to tour with her. They traveled all around Europe and Isadora could perform freely, creating a more innovative technique. She influenced the perception of dance at the time by giving the audience natural movement dance instead of rigid ballet techniques.

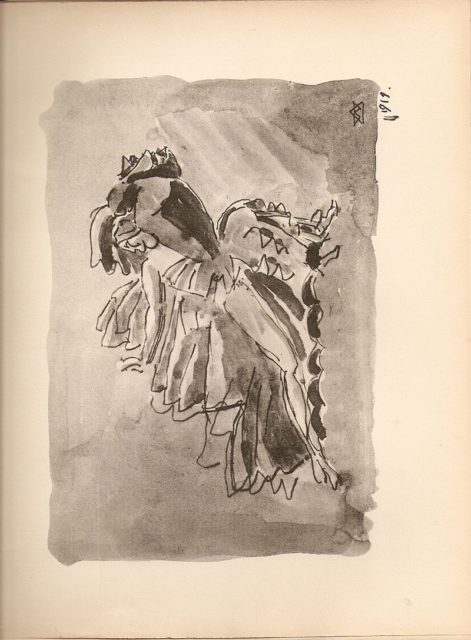

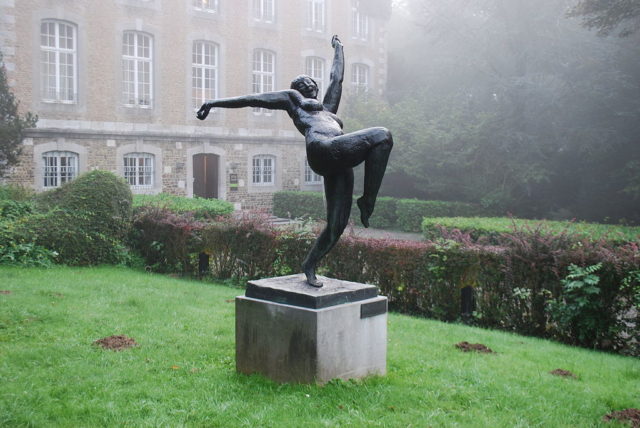

Even though the critics were divided in their opinion, Isadora inspired many artists such as Abraham Walkowitz, Arnold Ronnebeck, Auguste Rodin, and Antoine Bourdelle, who created works based on her.

Unusual for a stage artist, Isadora wasn’t fond of the commercial aspects of public performance, such as contracts and touring. Her mission was to share the dance and her philosophy of movement, so she opened schools and dedicated herself to teaching young people.

Duncan opened the first school in Berlin-Grunewald, Germany, in 1904. This was the place where the “Isadorables,” Isadora’s protégées, were educated. This was a group of six girls – Erika, Irma, Gretel, Maria-Theresa, Liesel, and Anna, who continued their teacher’s legacy, while the name “Isadorables” was given to them by the French poet Fernand Divoire.

Isadora legally adopted all six of them in 1919. She also opened a school in Paris, but it didn’t last long due to the outbreak of WWI.

Aleister Crowley, whom Duncan met in 1910, wrote of her: “Isadora Duncan has this gift of gesture to a very high degree. Let the reader study her dancing, if possible in private than in public, and learn the superb ‘unconsciousness’- which is magical consciousness – with which she suits the action to the melody.” – Aleister Crowley, “Magick: Liber ABA: Book 4: Parts 1-4”.

He also refers to Isadora under the name, “Lavinia King” in his “Confessions” and his novel “Moonchild.”

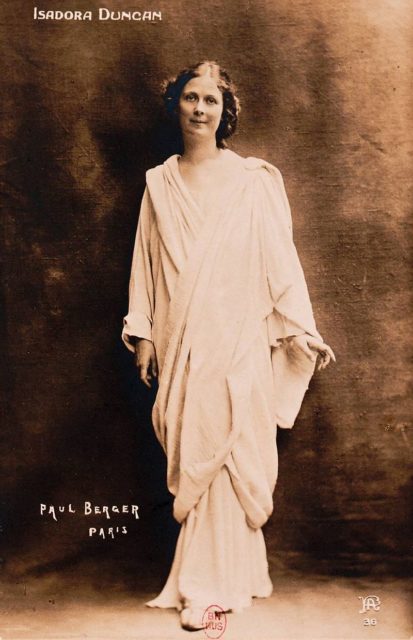

Duncan’s dancing costumes were also unique and extraordinary, as they allowed her to move freely and gave the impression that her body is extremely comfortable, which is the complete opposite of the corseted ballet costumes. Ancient Greek art always inspired Isadora’s clothes, and her most famous costume was a white Greek tunic she wore while barefoot. In 1911, while at a lavish party organized in a rented mansion, the Pavillon du Butard in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, by the French fashion designer Paul Poiret, Isadora, wearing a Greek evening gown designed by the host, danced barefoot on tables among 300 people and 900 bottles of champagne.

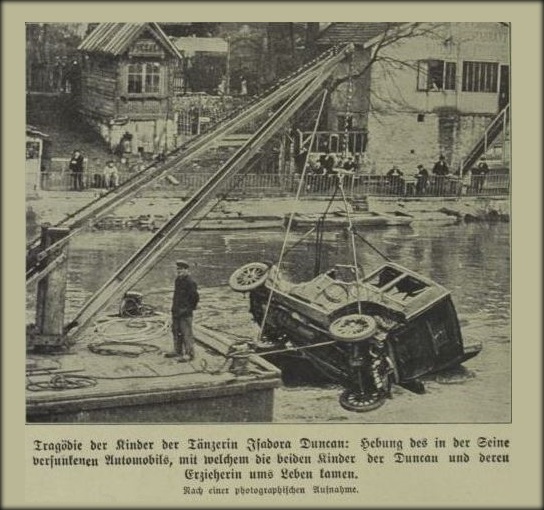

As much as she did not respect the rules and laws in dance, she was also less keen to observe morality and traditional mores in her way of life. She was an atheist, communist sympathizer, and bisexual. She had two children born in 1906 and 1910, one of which was with the theater designer Gordon Craig, and the second with Paris Singer. Both her children drowned with their nanny when their runaway car went into the Seine in 1913. It took Isadora years to recover from her children’s deaths and she never actually fully came back to herself.

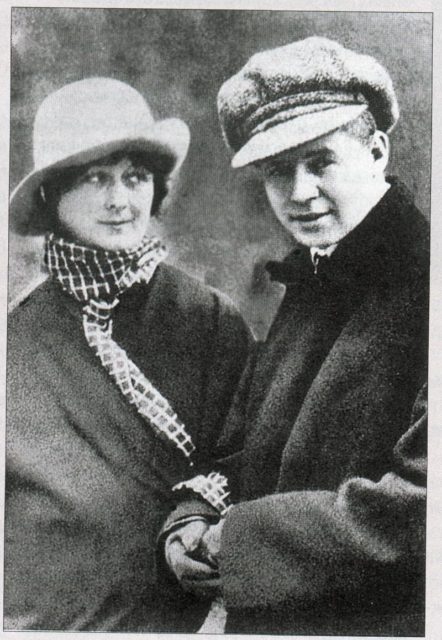

In 1921, Isadora moved to Moscow where she met the 18 years younger poet Sergei Yesenin. They married after a few months, and although Yesenin joined her on tour in the United States and Europe, after less than a year, he returned to Moscow, leaving the marriage.

He committed suicide in 1925. Isadora had a brief relationship with the poet and playwright, Mercedes de Acosta. Most of her later life featured her drunkness, debts, and love affairs.

In 1927, while driving with friends in Nice, in an Amilcar automobile, she wore a hand-painted, long, and flowing silk scarf, designed by the artist Roman Chatov. It was a present from her friend Mary Desti who was also driving in the car. The vehicle was open-air, and the most bizarre accident happened to Isadora – her silk scarf became entangled around the open-spoked wheels and rear axle while still draped around her neck. It hurled Isadora from the car and broke her neck.

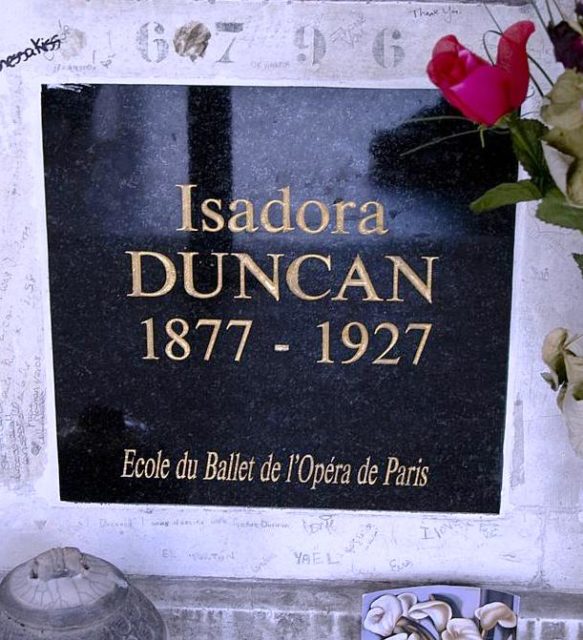

Following this horrific incident, Duncan was brought to the hospital and declared dead and was later cremated, and her ashes were placed next to those of her children, in the columbarium at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, 1927.