Ludwig II of Bavaria was perhaps one of the most eccentric European rulers of the 19th century. His reign was caught up in a time when his country was losing its political significance in Europe. Bavaria, locked between Austria and Prussia, was drawn into the conflict of the two competing German monarchies, out of which it stood on the Austrian side, which was the losing one at the time. Ludwig was 18 years old when he inherited the troublesome throne in 1864, and this defeat that occurred two years later marked his unsuccessful reign.

The next large event that distanced him from the role as an active ruler was the merging of Bavaria with the newly-founded German Empire. Since he was never interested in politics, he dedicated himself to the more finer things in life. Ludwig II, nicknamed the Swan King, was interested in art, architecture and most of all, Wagner’s music.

He inherited such interests, together with his name, from his grandfather, Ludwig I, who was fanatically obsessed with artifacts from Ancient Greece and the painters of the Italian golden age of renaissance. Ludwig I was an art collector, a patron of the arts and an artist himself. He was notorious for writing terrible poems, but nevertheless, his love for the arts was sincere and he was loved by the people. He managed to pass on this passion to his grandson, who took it to a whole new level.

Ludwig II insisted on building castles and participating in the entire process. Everything was to be approved by him personally, every piece of decoration, material, and furniture brought in was supervised by him, as these projects were of great importance to him, much more than worldly trivialities, such as running a country. He seemed to be trapped in a life of dreams. Ludwig II was a great fan of Wagner and his operas, so he offered his patronage to the aging composer.

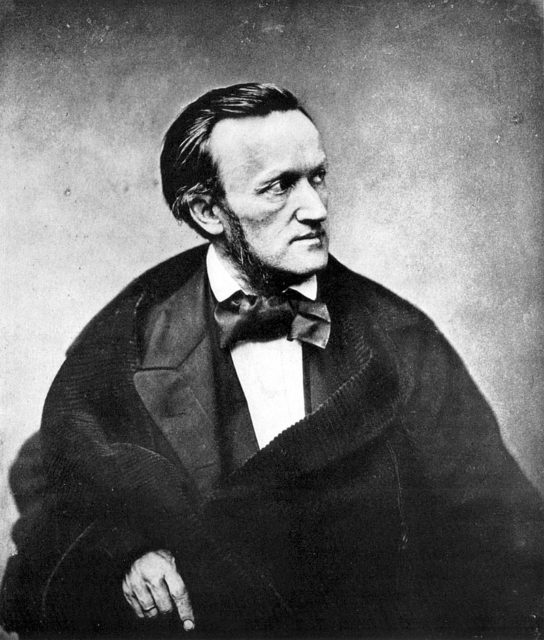

Wagner was 51 years old when he received an invitation from the young king to be his guest in Munich. The two extravagant figures got along great, and it was under Ludwig’s patronage that Wagner wrote his famous opera, Tristan and Isolde, one year after their meeting. This sponsorship came at a crucial moment for Wagner, as he was struggling with debt and poverty at the time. However, his extravagant lifestyle wasn’t suitable for the largely conservative Bavaria, so he left Munich and moved to Switzerland, where he was until receiving King Ludwig’s financial help.

Apart from music, King Ludwig loved theater.

One might think that this passion came from Wagner, but Ludwig’s fascination with theater was conceived well before the king became familiar with the composer’s work. So to say, it followed him through childhood. He worked to modernize the Munich theater, introducing its audience to Shakespeare, Calderón, Mozart, Gluck, Ibsen, Weber and other great names of European drama and opera. The King invested a lot in improving the cultural heritage of his country, working tirelessly to bring suitable actors and writers, in order to improve the standard of plays, most notably, the pieces written by Schiller, Molière, and Corneille.

But Ludwig’s true passion proved to be architecture ― castles, to be more precise. He started constructing the Neuschwanstein Castle in 1969. By 1871, Ludwig had completely abandoned politics ― a step that wasn’t taken lightly by the members of his staff. But his lack of interest came more as an act of rebellion, for he was opposed to the unification of Germany, as he didn’t approve of the Prussian dominance in the newly-founded monarchy. In the following years, he would erect magnificent building such as the Linderhof Palace, Herrenchiemsee Complex, and Munich Residenz Palace Royal apartment.

Ludwig nurtured a variety of styles ranging from Romanesque to Byzantine architecture, with elements of the Gothic interior. Neuschwanstein Castle, translated as the New Swan Castle, featured wall paintings that depicted images from folk tales that often inspired Wagner. He also built large gardens and castles that resembled Oriental structures.

He never abused his position as king to finance his projects, in terms of squandering tax money. Instead, Ludwig paid for these extravagant buildings out of his own pocket, or more likely from anyone who would lend him the money. He was often spending much more than he actually had. His opponent, Prince Regent of Bavaria Luitpold made attempts to declare the King insane, for he did suffer from melancholic fits and was considered odd by the members of his family.

All this together with his complete lack of interest for the Bavarian Kingdom contributed to the forming of a conspiracy group under the leadership of Luitpolde, who advocated Ludwig’s deposition from the throne. In 1886, it became apparent that Ludwig’s life was in danger, so he decided to escape Bavaria. He intended to cross Lake Starnberg and escape to safety, most likely Switzerland, but instead, he was found dead the following morning. The official cause of death was suicide by drowning, but considering the context in which it happened, it is highly unlikely. Later, evidence emerged that heated the rumors that the King was, in fact, assassinated.

Luitpold assumed the Bavarian throne but only as regent. His son, ironically also called Ludwig, was the last king of Bavaria, as he held the title until the end of the First World War.