Remember George Orwell’s famous quote from Animal Farm that “all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others”? Well, the story of George L. Cassiday, Jr. and how he supplied senators and members of Congress with alcohol ten years through the Alcohol prohibition seems like the perfect story that matches Orwell’s quote.

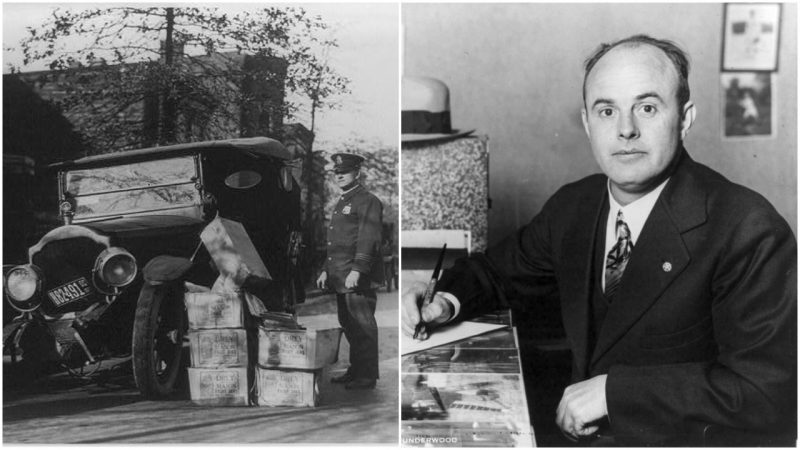

Cassiday had taken on bootlegging following a struggle to find a job after WWI. In fact, he became the leading Congressional bootlegger during the controversial ban across the US in the 1920’s. Though usage of alcohol was illegal for all citizens except for medical or similar purposes, apparently it was not an issue for congressmen and senators.

“A friend of mine told me that liquor was bringing better prices on Capitol Hill than anywhere else in Washington and that a living could be made supplying the demand,” he wrote in the Washington Post, in one of the six front page articles he published once his illegal actions were highlighted in 1930.

George’s articles provided other intriguing facts, for instance, that his first customers had been two southern congressmen who had voted the Eighteenth Amendment and its enforcement, the Volstead Act, the two legislation that had effectively established the prohibition.

After his second arrest on February 1930, Cassiday withdrew from bootlegging activities, and during the fall that same year, he went on to write the Washington Post articles. The shared information was sensational and pointed to the Congressional hypocrisy. He had shared how his illegal business started, from where he supplied the booze and how it was smuggled. George also spoke of how the Congress provided him the office to administrate all these activities.

According to Cassiday, he had met most members of Congress during those ten years of bootlegging, writing, “I would say that four out of five senators and congressmen consume liquor either at their offices or their homes.” Seemingly, the senators had been a bit more cautious.

Aside admitting responsibility for bootlegging, Cassiday also said that Congress was accountable as well, writing, “Considering that I took the risk and did the leg work from 1920 to 1930, I am more than willing to let the general public decide how I stack up with the senator or representative which ordered the stuff and consumed it on the premises of transporting it to their home”.

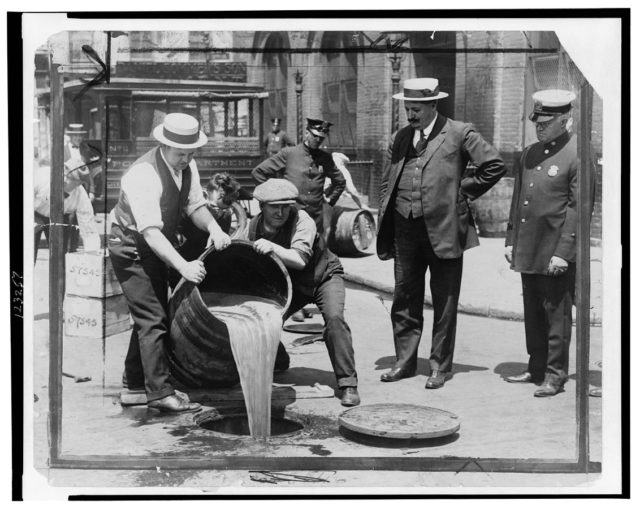

His final article was published exactly one week before the midterm election day in 1930 and directly contributed to the voting results. As the Republicans were defeated in the voting, the power shifted to a newly elected Democratic majority. The Prohibition was canceled by 1933.

After the 1930 arrest, Cassiday served 18 months in jail, though he never spent a night sleeping in prison. He was allowed to sign out at night and come back to prison the next morning. Later, he worked in a shoe factory and hotels around Washington. From the bootlegging days, Cassiday kept a “black book” that included information about each customer and their purchases; his wife destroyed the book, and the exact names were never revealed to the public. All we have are his words admitting that those customers were mostly members of the Congress. Cassiday is also remembered as the “man in the green hat,” and in 2012, the first post-Prohibition distillery in Washington launched “Green Hat Gin,” named after him.

Read another story from us: Prohibition and speakeasies in the US

The prohibition remained a notorious amendment in US history and is also related to speculated radical enforcement, additionally employed by the government. Allegedly, the most drastic measure was when federal officials considered putting poison in industrial alcohols, which were sometimes stolen from producers by bootleggers, and then resold as drinkable spirits. The officials believed that a little poison could scare people away and make them give up drinking. Supposedly, the radical measure took the lives of over 10,000 people.