David Rumsey collects maps, but not just any maps, his collection of old print maps is one of the largest private collections. At last count, it contained 150,000 of these maps, and the 69-year-old is still adding to his collection. Many people like to look at old maps and discover what an area looked like in the past; for these people, what Rumsey is doing with his maps is very exciting. On his website, there is a digitized sub-collection that the public can explore; it contains 38,000 maps at present and is increasing yearly.

Previously a teacher and artist, the New Yorker started collecting old maps, having always been fascinated with the area of art and its intersection with technology. He has created a series of interactive maps that you can layer on top of Google Earth and Google Maps to see what has changed over time. He also plans to launch a geo-referencing tool, like that of the British Library, that will allow a user to be involved with the digital mapping process.

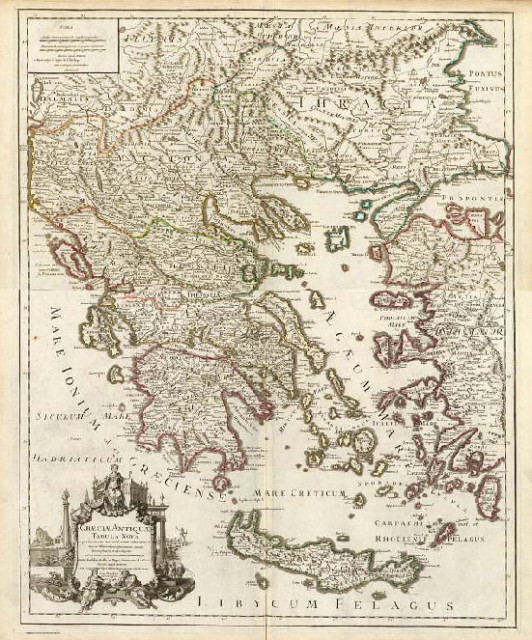

Rumsey feels that maps talk to people in a straightforward way, which is why they are so popular. Anyone can read a map once they realize what the marks mean. Rumsey believes it is the best way to teach history. His maps start from around the 1700s when mapping became more scientific in its depictions. Surveying tools were starting to be used, as well as the triangulation that helps get the right perspective down on paper for a drawn map.

Rumsey is very much a proponent of open access, and the Web is an amazing opportunity to offer that. He considers the Web as a tool that allows users to access academic world primary sources, where you can view and access the original map or the original book. These are usually hidden away in some private collection and very rarely see the light of day.

His Google Earth layering collection works by scanning the old map and then opening that in a GIS program specific to geo-referencing. You end up with two screens side by side. Then you need to start the time-consuming task of matching. You match 60-100 points using individual marks; once you have done that you can tell the program to recalculate the old map into modern geographical space, using your markers to match specific areas. It rebuilds the whole image so you can then open it with Google Earth and it will appear in the right spot, CityLab reported.

It is a lot of work on his part, but Rumsey hopes that viewers of his site will be able to compare the past and present to get a clearer idea of how the land changes. He considers each map to be an archive of information. On his site, he has a German map showing the unification in the 1870s – Germans are sticklers for detail on their maps, so where a forest is shown, it has keys for every type of tree. Others only provide a broad key to designate a forested area.

For the future, Rumsey is hoping scanning technology paired with optical character recognition will read the maps and list what is written on them, such as names of towns or rivers, in this kind of fine detail.

Rumsey’s maps are also helpful for scientists across many fields, as they show coastlines as they used to be and forests, lakes, and settlements that may not exist anymore. His site not only has maps but many images as well; it is worth a visit.