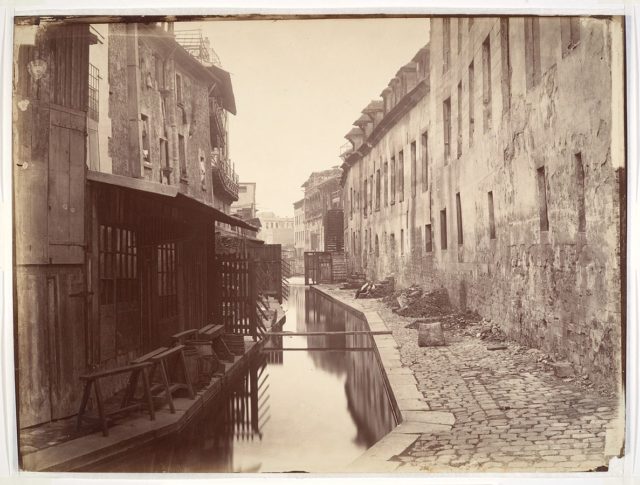

By the middle of the 19-th century, Paris was overcrowded, dark and even dangerous and hazardous. It was not the city we all know today.

The French social reformer, Victor Considerant noted: “Paris is an immense workshop of putrefaction, where misery, pestilence and sickness work in concert, where sunlight and air rarely penetrate. Paris is a terrible place where plants shrivel and perish, and where, of seven small infants, four die during the year.”

Additionally, Voltaire in the 18-th century noted that the markets in the French capitals were “established in narrow streets, showing off their filthiness, spreading infection and causing continuing disorders.” He also wrote that the Louvre was admirable, “but it was hidden behind buildings worthy of the Goths and Vandals.”

Before renovations took place, some parts of the central area had remained almost the same since the Middle Age. Also, population density in this central area of Paris became extremely high, compared to the rest of the city. Overpopulation was the reason why cholera and similar diseases spread so rapidly. Such epidemics ravaged the city in several occasion, and in 1848 they were even the cause of death for five percent of the inhabitants in the central neighborhoods. Traffic was another issue, a mess, where wagons, carriages, and carts could barely move through the narrow streets. Last but not least, the city center was a boiling pot of discontent and revolutions.

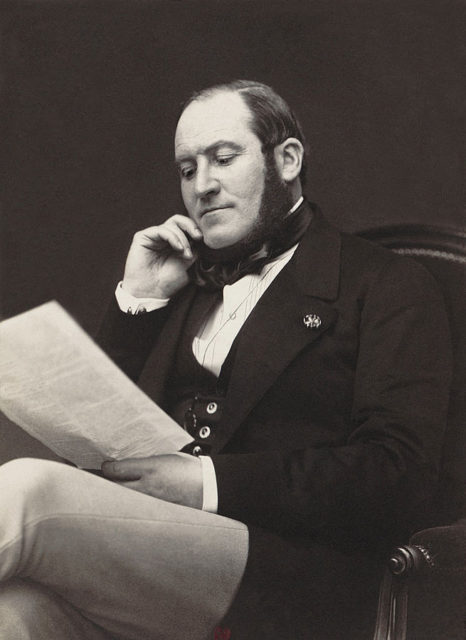

Despite ambitious plans to revive and refresh the center of Paris, which were speculated for many years, nothing significant happened until Napoleon III came to power and granted authority to Haussmann, probably the Perfect of the Seine.

Today’s Paris was built under the reign of Napoleon III (who held power after conducting a coup d’etat) and the work of Haussmann. Renovations of Paris hailed as old, dark, overcrowded, dangerous, and unhealthy. They started in 1853 and continued until 1927, although Hausmann was dismissed in the course. Three phases of renovation took place, and the first one began in 1853, concentrating on the completion of a great cross in the city center.

The cross enabled easier commute from east to west along the rue de Rivoli and rue Saint-Antoine, and north-south by building two new boulevards, Strasbourg and Sébastopol. These first projects were fast finished as Paris was to host the Universal Exposition of 1855. The city got its first luxurious hotel, Grand Hôtel du Louvre, that was to house the Imperial guests at the prominent event.

Haussmann enjoyed great freedom under Napoleon III as he wasn’t obliged to report to the parliament which was less influential back then. The emperor took care of the finances, and despite money were flowing from the Parliament, he further hired investors and bankers to raise funds for reconstruction of the streets and boulevards. In return, investors were given rights to develop real estates along the route they financed.

Slowly, the ancient, dark and narrow streets of old Paris started to disappear from the map. By the end of the first phase, Haussman had completed almost 10,000 meters of new boulevards. The official parliamentary report of 1859 states that the first renovation stage of Paris had “brought air, light, and healthiness and poured easier circulation in a labyrinth that was regularly blocked and impenetrable.”

Also, thousands of workers were employed, and Parisians were pleased by the initial results. Renovations proceeded to the second stage, from 1859 until 1867. This time, the island in the midst of Seine transformed into an enormous construction site and was completely changed. For instance, the square in front the Notre Dame was widened, and the spire of the Cathedral which was pulled down during the Revolution was now restored.

Though approved by the public, some criticism was inevitable. Haussman was particularly hailed for taking large parts of the iconic Jardin du Luxembourg to make space for the present-day Boulevard Raspail, and for its connection with the boulevard Saint-Michel.

By the third renovation stage which started in 1869, times changed and the parliament was getting stronger as Napoleon III was becoming increasingly ill.

Hausmann was dismissed during this stage. In his memoirs, written many years later, the Prefect would comment on the dismissal: “In the eyes of the Parisians, who like routine in things but are changeable when it comes to people, I committed two great wrongs: Over the course of seventeen years, I disturbed their daily habits by turning Paris upside down, and they had to look at the same face of the Prefect in the Hotel de Ville. These were two unforgivable complaints.”

Today, the Haussmann apartment buildings, which line the straight and wide boulevards of Paris, make one of the most recognizable features of his conducted renovation plans. Before Haussmann, most buildings in Paris were made of brick or wood. He also required that all buildings must be regularly maintained and cleaned, at least every ten years. Simultaneously, the construction plans rebuilt the dense labyrinth of pipes, sewers, and tunnels under the streets, which provided essential services to the French capital.

The critics

Many critics considered that what Haussman did was over-the-top. In 1867 the French historian, Léon Halévy wrote that “the work of Monsieur Haussman is incomparable. Everyone agrees. Paris is a marvel, and in fifteen years M. Haussmann has done what would probably not be done in a century. But enough for the movement.

The 20-th century is ahead. Let’s leave something for the others.” Presumably, Haussmann had destroyed essential historic parts of the city and the Paris of Balzac or Voltaire slowly disappeared.

Possibly the most intriguing critics were those who speculated that the real purpose of Haussmann’s renovations, and particularly the wide boulevards, were to make it easier for the army to maneuver and suppress armed uprisings. These critics further argued that a small number of large and open intersections were designed as such for a simple control by a small force. Such arguments and comments persisted through the 20-th century.

The French historian, René Hérron de Villefosse, would note that: “the larger part of the piercing of avenues had, for its reason, the desire to avoid popular insurrections and barricades. They were strategic from their conception.”

Haussmann himself did not neglect that there was a military value of the wider streets. He would note that the newly built boulevard Sebastopol resulted in the “gutting of old Paris, of the quarter of riots and barricades.”

He had further admitted that sometimes he used the military value as an argument to get more financial support from the Parliament to justify the high costs of the projects, arguing that the defense was of national importance.

The casualties of the megalomaniac construction projects of Haussmann were numerous. He was further blamed for social disruption. Thousands of families and businesses had to relocate from the central area as buildings were demised to open the space for the wide boulevards.

Read another story from us: Saint-Étienne-du-Mont is one of the jewels of Paris churches

The housing for socially endangered families was drastically reduced while the rents were dramatically increased.