Between 1930 and 1940, the American Midwest suffered one of the most devastating human-made disasters the country had ever seen. Congress passed the Homestead Act in 1862; it gave farmers willing to relocate to the mid-western states 160 acres of farming land. The prairie land was covered with natural grass with deep roots that kept the soil moist and in place. Farmers began to plow up the land and plant wheat instead. Wheat is a shallow-rooted grass that was in high demand at the time because of shortages caused by the Russian Revolution and the First World War.

Removing the natural plant cover, along with a severe drought that lasted for years, caused “black blizzards” – prairie winds that carried away the failed wheat crop and loose topsoil. Black Sunday, a storm in the spring of 1935, blew so much topsoil eastward that Chicago received millions of pounds of fine, gritty dirt that coated the entire city. Cars and trucks would not start. Women tried to keep the dust out of their houses by hanging wet sheets over the windows and stuffing newspaper in the cracks, but nothing made much difference.

The storm reached the east coast two days later and covered Buffalo, New York City, and Boston. The following winter, the snow in New England was red. The storms blackened the skies, turning day into night; livestock, unable to breathe, fell dead in the fields. Billowing clouds of dust rolled across the plains, leaving drifts that almost covered houses and barns. Respiratory problems such as “dust pneumonia” were on the rise, even though most people and some animals wore masks outside. The summer heat was unbearable, with temperatures topping 100 degrees for weeks at a time and no trees available for shade. Over 350 houses had to be demolished after one of the more devastating storms. In 1932, fourteen dust storms were observed; the following year the number increased to more than thirty.

By the end of 1933, the harsh conditions caused an exodus of the displaced families from Northern Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and the outskirts of the Great Plains. The migrants came to be known as “Okies,” “Arkies,” or “Texies” – those who had lost everything and were struggling the most. The Dust Bowl migration was the largest population change in American history in such a short period.

Many migrants went to California and Oregon looking for work picking fruits and vegetables. Between 1930 and 1940, approximately 3.5 million people left the Great Plains. In just over a year, more than 86,000 people migrated to California – more than the number of prospectors who flooded the Northwest during the 1849 Gold Rush. Over 500,000 Americans were homeless – most of them believed they had to abandon their farms in search of work to support their families.

This was also the time of the Great Depression. Cities, strained to the limit, were trying to help the communities and the incoming migrants. Many new projects were put into effect by then-President Franklin Roosevelt. The Resettlement Administration (RA) relocated struggling families to communities established by the federal government. Between April 1935 and December 1936, the RA constructed 95 camps and gave migrants clean quarters with running water, electricity, and indoor plumbing. There were many more in need than the 75,000 people who had the benefit of the camps, and even those who found a place at the camp were only allowed to stay there on a temporary basis.

Finally, the rains resumed in the autumn of 1939. Roosevelt’s policies and the approach of World War II helped America recover from the Depression. Some families returned to their farms and were taught new farming techniques that improved the soil and reduced erosion. Trees were planted across the Plains as wind blocks. The government bought huge tracts of land and allowed it to return to natural prairie grasses. While some areas of the Oklahoma panhandle may never be safe from the winds, the majority of America’s heartland has returned to golden wheat fields.

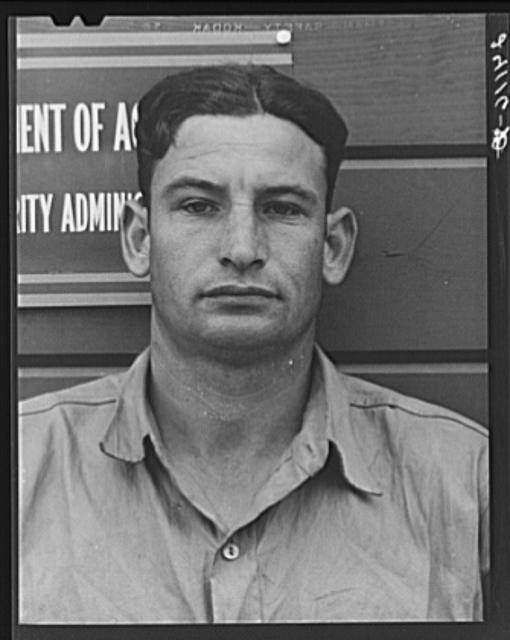

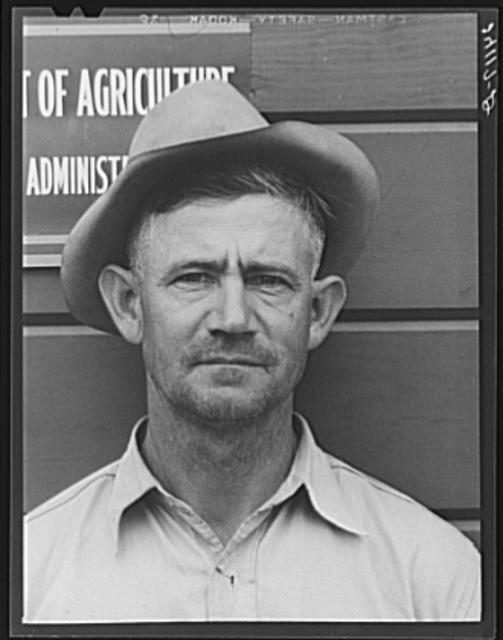

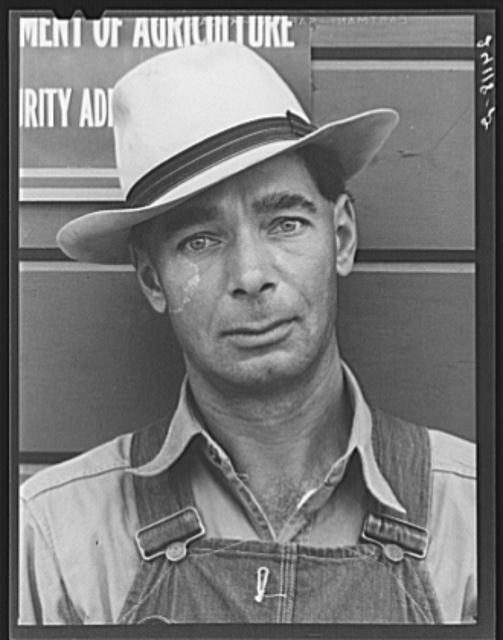

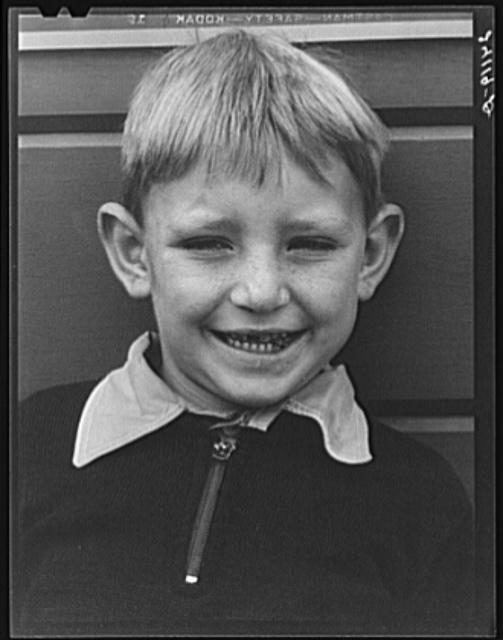

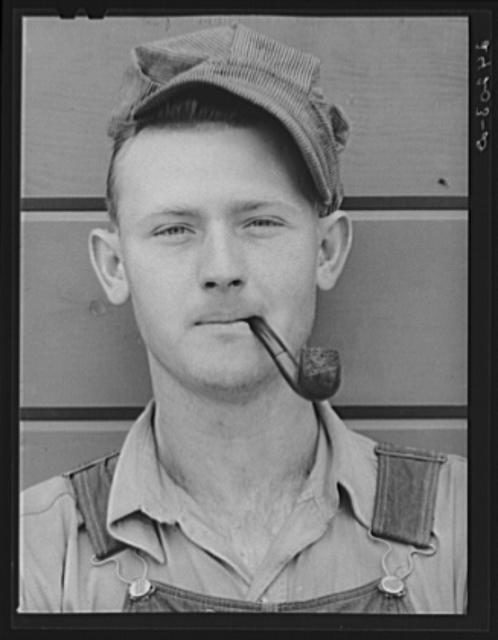

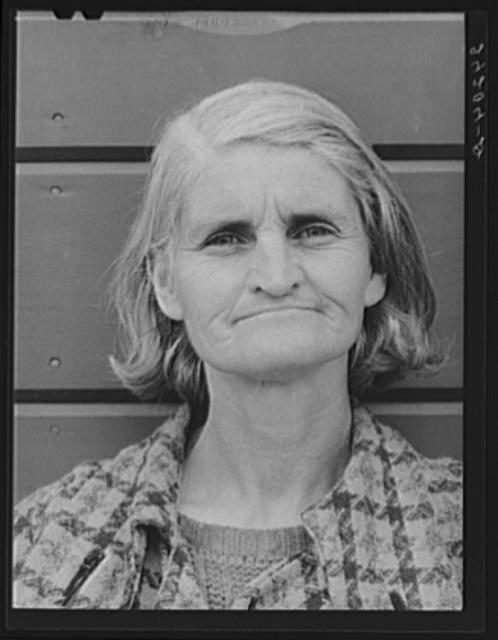

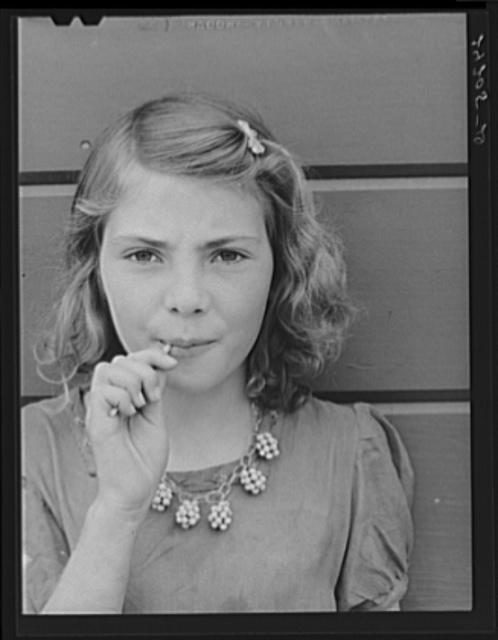

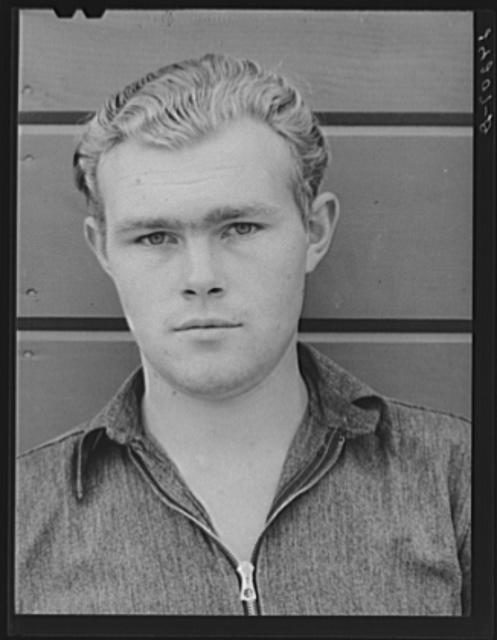

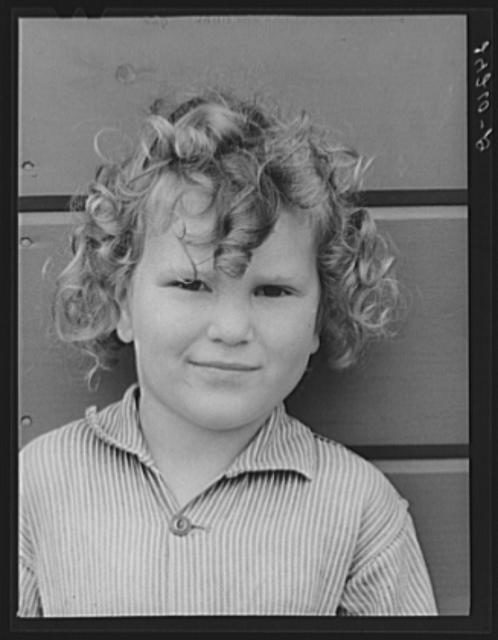

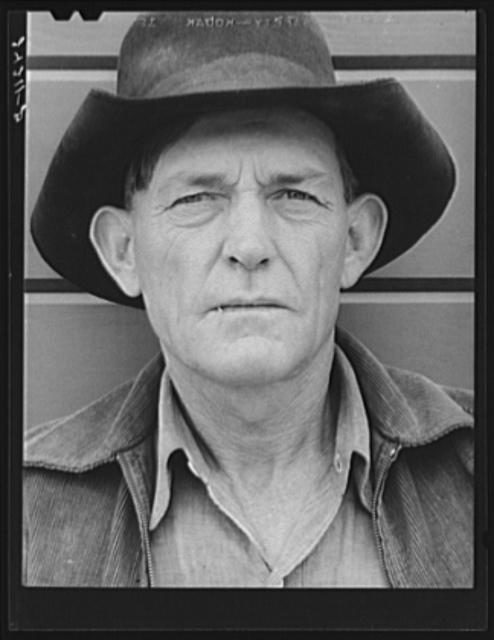

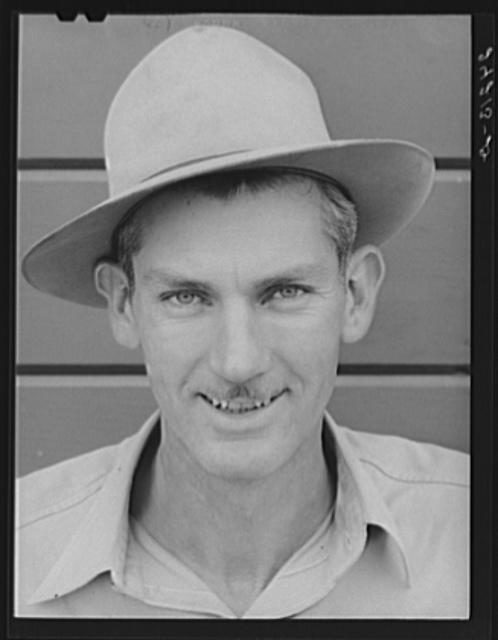

FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein captured these images of the men, women, and children of the Dust Bowl migrations.