When it comes to natural wonders, 2017 has not started so well. On 8 January, we said goodbye to the iconic and more than 1000-year old Pioneer cabin tree in California, and on 8 March, the small nation of Malta witnessed a major loss in natural heritage as their famous Azure Window collapsed into the sea. Some reports had indicated that with time, the Maltese natural wonder would eventually collapse, but most people did not anticipate it would happen so soon.

However, that’s how things go in nature, and these famous natural landmarks are neither the first nor last that have vanished from the face of the Earth. In history, many more wondrous natural sites have sadly disappeared. From some of them, there is not a single trace left, and some of them are far away from the full beauty and glory they once had.

1.Jump-off Joe, United States

During the late 19th century, the Jump-off Joe emerged as an eminent coastal feature at the Oregon’s Nye beach in the proximity of Newport. It is considered that this genuine rock formation was created due to a shift of tides in the ocean following rapid constructions of docks at the local Yaquina Bay.

The site formed after a huge sandstone landmass which extended some 150 into the waters eroded as the new tides appeared. By the beginning of the next century, Jump-off Joe adorned the Nye beach with its prominent arch and its reminder that perhaps reminded people of a dinosaur tail. People also needed to jump over it in order to continue moving to the beach, hence the name Jump-off Joe.

The formation enchanted everyone with its strange beauty and both settlers and Native Americans started to come up with several stories about it. As Jump-off Joe transformed the Nye Beach into a real hit, there was even a thriving local business that made use of photographs from the site and sold them as postcards.

Jump-off Joe was particularly famous before World War One, but its popularity sadly started to diminish when its arch collapsed in 1916. Over the period of the next five decades, the formation gradually continued to disappear, and by the 1990s there was hardly any trace of it left.

2.The Twelve Apostles, Australia

Also known as the Pinnacles, and even the Sow and Pigs, the Twelve Apostles of Australia were never actually twelve in number but still became quite a popular destination to visit, roughly a four-hours drive from the city of Melbourne.

This wonder of nature formed thanks to a constant erosion of the limestone cliffs of the Victoria mainland, a process that probably commenced as early as some 10 to 20 million years ago. The waves and the winds of the Southern Ocean have taken its toll on the mainland, eventually forming caves in the cliffs.

Over time, those caves transformed into arches, which eventually became rock stacks emerging out of the sea, distinct from the coastline, and reaching a height of up to 145 feet. The site is especially spectacular at sunrise or sunset when the yellowish color of the stacks changes into darker tones.

Unfortunately, the number of the Twelve Apostles has been constantly decreasing too. As of 2005, one of the nine remaining collapsed, making a new total of eight sea stacks. As the ocean waves continue the eroding processes, the demise of all sea stacks seems inevitable in the future.

The good news is that new sea stacks could form out of the cliff that currently faces the Apostles. We are still to see whether those newly-formed stacks position in a new extraordinary setting similar as the Twelve Apostles did in the past.

3. Wall Arch in Arches National Park, United States

In 2008, Utah’s Arches National Park forever lost one of its most prominent features, the famous Wall Arch. This unique rock structure collapsed suddenly – an event which park officials expected as fractures were evident on the arch itself. However, little did they anticipate the moment will come so soon. The Wall Arch was a second notable feature of this type which the park lost in the recent decades. Another similar in proportions arch fell in the park back in 1991.

The Wall Arch was discovered and picked its name in 1948, and at the moment when it collapsed in 2008, it counted as the twelfth in size among the parks’ two-thousand arch compositions. What’s further interesting about the Wall Arch is that it was made of specific rock deposit, namely the Entrada Sandstone which appeared as early as some 180 million years ago throughout the Jurassic era.

While the Entrada Sandstone as a material is prone to surrender to forces of nature, gravity or erosion, it is still quite rare to observe an event such was the Wall Arch collapse. Therefore, nobody reported on actually seeing the arch fall, neither there were any injured according to the National Park officials.

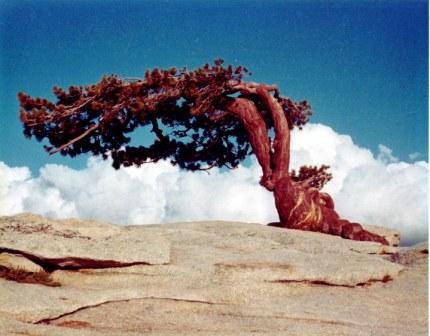

4.The Jeffrey Pine atop the Yosemite’s Sentinel Dome, United States

At the ultimate pleasure of any tree hugger in the world, there is a fair enough number of remarkable trees to be seen and enjoyed around. Be that the famous Angel Oak tree found east of Mississippi river, or perhaps the 3,200-year-old President Tree that makes one of the most memorable sights at the Giant Forest in California.

Nevertheless, none of these counted as one of the most photographed trees of all times as good old Jeffrey Pine did, perching over its impossible spot at Sentinel Dome in Yosemite National Park.

First photos of Jeffrey Pine appeared as early as 1876 thanks to photographer Carleton Watkins, and its fame only grew as eminent American photographer and environmentalist, Ansel Adams, featured the tree in his outstanding black and white series of photographs from the American West later on.

Unfortunately, the life of Jeffrey ceased following a harsh drought as of 1977. The tree remained to occupy its place on Sentinel Dome for few more decades after it eventually fell in August 2003 when severe storms hit the area.

One of the biggest reasons why Jeffrey pine was so appealing to everyone, not only photographers, was certainly its unique location on the Sentinel Dome. As a real wonder of nature, the tree had managed to grow out of the cracks in the granite, seemingly without soil, and atop one of the highest peaks in the entire park.

According to park officials, Jeffrey was roughly four centuries old and its height measured some 12 feet. It most likely grew from a seed dropped by a bird, which had succeeded to root through the hard granite.

5.El Dedo de Dios, Canary Islands, Spain

For many years, the site of El Dedo de Dios served as an ultimate inspiration to numerous artists and creatives, however, this prominent sea stack that stood north of Gran Canaria, off the coast of the Atlantic, was sadly claimed by the ocean after a tropical storm hit the area back in 2005.

Its name translated to “God’s Finger” but after the violent hurricane season that year, there is nothing left of the finger.

Geologically speaking, the area where Dedo de Dios once proudly stood, is the oldest on Gran Canaria, having started to form roughly some 14 million years ago. As records suggest, the strangely-shaped stalk needed a period of well over 200,000 years to form out of basaltic materials.

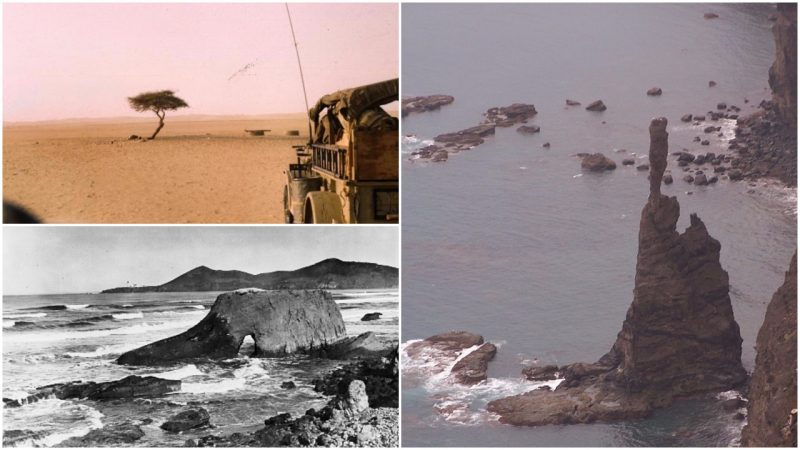

6.Mukurob, Namibia

Down in Namibia, there was yet another Finger of God which lurked hidden in the Namib desert and collapsed on 7 December 1988. Mukurob was a sandstone rock formation and counted as one of the greatest tourist attractions of the African country. For the local Nama people, it was almost sacred, as for generations the site was a source of all kinds of tales and legends, narratives which provides explanations of the structure’s origins.

One version of the Mukurob-related stories, tells of a tension among the local Nama people and another group known as the Herero people. Allegedly, the Herero group mocked the Nama because all they had was rocks, but not cattle which the Herero had in abundance. “Look here, how rich we are, with our nice fat cattle,” would brag the Herero.

The Nama were quick to annoy their opponent by saying that they still had this “very special rock”. They believed that as long as the Mukurob stood proud and tall, they would have no problems in controlling the area. Naturally, the Herero tried to bring down the rock. No matter how hard they tried, the rock did not surrender.

Furthermore, the Mukurob has a political importance. The Nama people believed that the site could collapse only once the power of the “white man” comes to an end. In reality, Namibia first made a colony of the Germans, and later its territories were controlled by South Africa. And as historical events go, Mukurob did collapse on the night of 7 December 1988, just a couple of weeks after South Africa relinquished control of Namibia (then called South West Africa). Namibia would gain independence two years later, on 21 March 1990.

The reasons why this sandstone formation collapsed are still uncertain. Some believe it was a rainstorm that hit the area shortly before the collapse, which would have normally weakened the strange structure. Another study suggests that it may have even been an earthquake which happened as far as Armenia, but strange enough was registered in Namibia too.

7. The Ténéré Tree, Niger

Once upon a time, the Ténéré tree claimed the status of Earth’s most isolated tree of all. It may have looked sad and alone on the horizon, amid the endless sand of the Nigerian Sahara, but for numerous travelers who traversed the old caravan route passing through this remote and desolate terrain, the tree was a lot more than just a shade from the sun. It offered a strange comfort, a notion that one is not alone in the desert. It was the single tree a traveler could see in an area of about 250 miles.

The Ténéré tree was also special as it belonged to the final group of trees that sprouted during the times Sahara was still able to provide for life. Its roots were found to be going some 118 feet below the ground, which was nothing but a proof that life can thrive even under most unbelievable circumstances.

Sadly, a stupid human mistake proved fatal for the Tree of Ténéré, as it got knocked down by a drunk truck driver back in 1973.

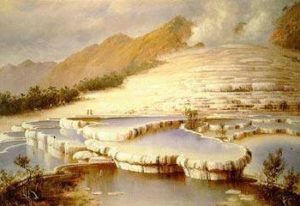

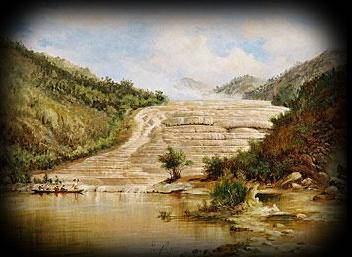

8. Te Otukapuarangi & Te Tarata, New Zealand

Last but certainly not least, Te Otukapuarangi & Te Tarata resembled one of the most remarkable natural wonders to be found in the South Pacific. The first was further known as the Pink Terrace and in Māori its name stood for “the fountain of the clouded sky”; the former, known as the White Terrace, meant “the tattooed rock”.

Back in the day, these were two springs distanced not even a mile from each other and counted as the largest silica sinter deposits on our planet. Sadly, an extremely violent eruption of Mount Tarawera in 1886 proved fatal for both the springs. Reportedly, it was such a rough eruption that it was heard all the way to Auckland, while its blast left a 10-miles-long rift that crossed the mountains, passed through the lakes, and extended beyond the area.

The White Terrace used to be at the north-east end of the current Lake Rotomahana, and Te Tarata occupied a spot to the lake edge some 82 feet below. After the eruption, what was left of this natural wonder was only a crater, some 320 feet in width.

The crater filled with water several years after the volcanic eruption. Despite the new lake was ten times larger and deeper than the old springs, the site never redeemed its former beauty and authenticity.