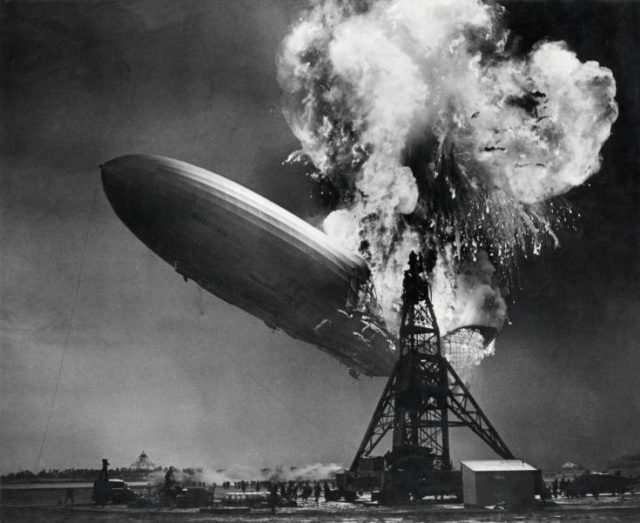

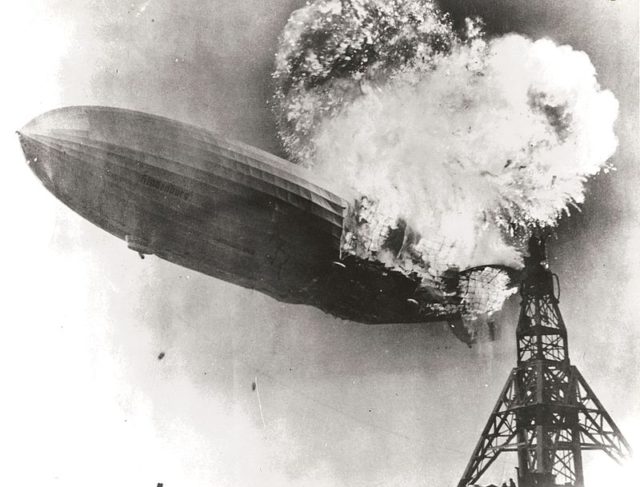

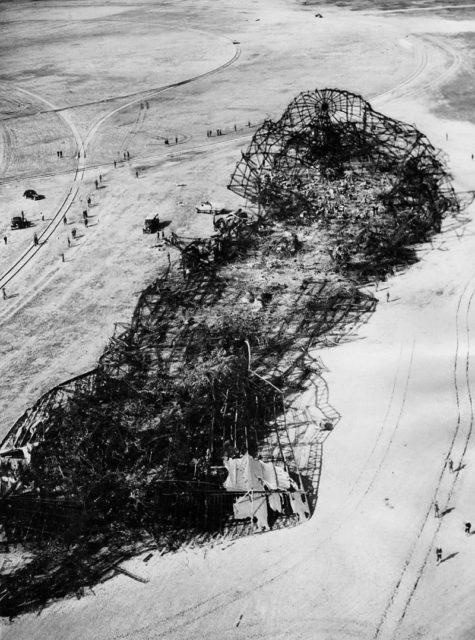

On May 3, 1937, as the German zeppelin airship Hindenburg was attempting to land at Lakehurst, New Jersey, a spark reacted with a hydrogen gas leak and caused an explosion.

Within thirty seconds, a thirty-year-old mode of travel came to a halt. Thousands of passengers had used zeppelins to travel across the ocean with few incidents until the Hindenburg disaster. The airship was concluding its sixty-third flight, with a crew of sixty-one serving thirty-six passengers.

The following are some facts about the Hindenburg that many people don’t know.

1. A smoking room was provided under the storage space that was used to store the hydrogen gas:

The Hindenburg allowed passengers to travel from Europe to the Americas in almost half the time it took to travel by sea. The airship boasted elegant dining and luxurious passenger quarters. Although the ship was filled with seven million cubic feet of extremely flammable hydrogen gas, a gentlemen’s smoking room was available.

Passengers could buy cigarettes and Cuban cigars on board and light up with specially provided lighters in a pressurized room, designed to stop any hydrogen gas from entering. A guard was posted to control the double door entrance and to make sure all smoking materials had been extinguished before a passenger left the room. The smoking room was located at the bottom of the ship, and since hydrogen is lighter than air, any leaking gas would have escaped upward.

2. A special lightweight piano was built for the Hindenburg:

The Hindenburg’s owners, the German Zeppelin Transport Company, contracted the highly respected piano manufacturing company, Julius Blüthner, to provide a lightweight baby grand piano to accommodate the airship’s stringent weight allowances.

The piano, which weighed less than four hundred pounds, was used only during the first year of service and was not on board for the last voyage.

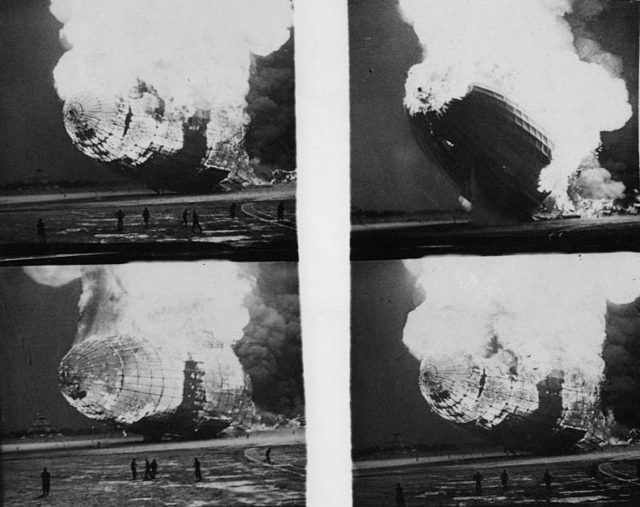

3. The survivors greatly outnumbered the victims:

Sixty-two of the passengers and crew on board survived. Many of the survivors jumped out of the windows and ran to escape the fire.

Thirteen passengers and twenty-three members of the crew, including a crew member on the ground, lost their lives when the ship caught fire.

4. Mail carried aboard the Hindenburg survived and was delivered:

Zeppelins established airmail service across the ocean. The Hindenburg carried nearly seventeen thousand letters and documents on its final voyage.

Even with the scorching heat of a hydrogen gas fire, over one hundred fifty items stored in a protective box survived the crash.

The surviving pieces of mail were postmarked four days after the disaster and were eventually delivered. The letters, when put up for sale, draw some of the highest prices of any ephemera.

5. Goebbels wanted to name the ship after Adolf Hitler:

Reich Minister of Propaganda of Nazi Germany and a member of Hitler’s inner circle, Joseph Goebbels, wanted the new airship to be named after the leader of the Nazi party, Adolph Hitler.

Dr. Hugo Eckener, head of the Zeppelin factory at Friedrichshafen on Bodensee in Württemberg, Germany, was not a Nazi supporter and chose to name the ship after former German president Paul von Hindenburg. In the end, Hitler was pleased that the doomed ship did not carry his name.

6. The famous radio broadcast of the Hindenburg disaster was not live:

Herbert Morrison, a radio reporter for Chicago radio station WLS, was covering the arrival of the Hindenburg.

His emotional account of the fire was taped and not heard in Chicago until later that night, and was not released nationwide until the following day.

Media outlets synchronized his audio report with newsreels when playing the video coverage of the disaster, and Morrison’s now famous remarks, “Oh, the humanity!” were heard around the world.

7. The Hindenburg disaster was only the third deadliest airship accident:

While the Hindenburg is the most famous zeppelin accident, there were two previous incidents with much higher mortality rates.

On April 4, 1933, the helium-filled U.S. Navy airship, USS Akron, crashed during a storm off the coast of New Jersey; of the seventy-six on board, all but three were killed.

The October 5, 1930, crash of the maiden voyage of the British rigid military airship R101 in France, claimed forty-eight of fifty-four lives, including Air Minister Lord Thomson, the founder of the Zeppelin program, important government bureaucrats, and many ship designers from the Royal Airship Works.