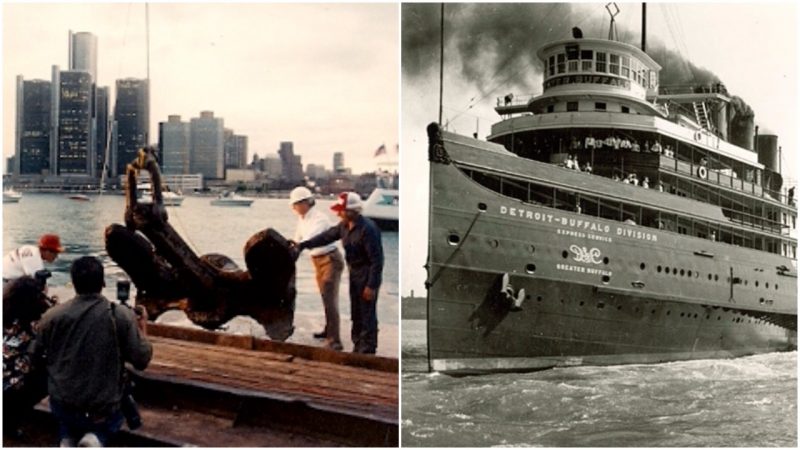

In November 2016, three divers working for the Great Lakes Maritime Institute dove twenty feet under the chilly waters of the Detroit River. Their goal was to attach cables that would raise the 6,000-pound anchor that once belonged to the regal side-paddle steamer named the Greater Detroit.

The Greater Detroit was created by one of the best naval architects working in the Great Lakes region, Frank E. Kirby. In 1922, he designed a side-paddle steamship and took the plans to the Detroit & Cleveland Steamboat Line. They ordered two of these ships to be built.

The Greater Detroit and her twin sister, the Greater Buffalo, were 536 feet long and had a beam width of 96 feet; when they were built, they were the largest side-wheel paddle steamers in the world. They were powered by the mightiest steam engines in the world at that time; the three-cylinder engines drove them through the water at 21 knots.

These extremely expensive ladies of the Great Lakes were the most modern and luxurious form of travel for passengers journeying between Detroit and Cleveland and Buffalo in the East, or between Detroit and the Straits of Mackinac in the north during the spring, summer, and fall.

Boarding in the late afternoon, usually around 5:30 pm, there was plenty of time for the 2,127 passengers to enjoy sundowners, a sumptuous dinner, and a good night’s sleep in one of the 625 staterooms before arriving refreshed at their destination. Passengers could also elect to have their motor vehicles transported on the deck, where the ships each had room for 103 cars. The steel-hulled Greater Detroit was launched on September 15, 1923, in Lorain, Ohio by the American Ship Building Company.

She was then towed to Detroit to have her superstructure constructed and to be completely outfitted inside. It took over a year for an army of workers to build the superstructure out of wood and plaster, and then to paint and install all the luxurious fixtures and fittings. She was put into service on August 29, 1924, with 275 officers and crew.

The trip between Detroit and Buffalo was reputed to be one of the most scenic trips that could be taken. There was an unending supply of interesting things to see. Apart from the birds and wildlife, there were villages and towns that dotted the shores of the lake. In the evening the night sky was filled with stars, and the romance of traveling by ship would not have been lost on the passengers.

The shipping line took the safety of their passengers extremely seriously. As the superstructure of the vessel was wood and plaster, fire was a constant fear. The Greater Detroit had a full sprinkler system installed that included automated fire alarms and fire walls and doors to provide the opportunity to block off sections of the ship in an emergency.

In addition to the fire suppression system, the vessel had a double hull with 16 watertight compartments so, if she ran aground, the water could be restricted and not flood the entire vessel. To ensure that the ship was safe at night, there was a full-time night watchman to keep a lookout.

Sadly, time and technology do not stand still; by the 1930s business at the shipping lines was starting to become difficult. At the beginning of the 1930s, the company barely managed to stay afloat during the Great Depression – motor cars were rolling off the manufacturing lines in Detroit in ever-increasing numbers, which encouraged people to drive rather than travel by boat.

The company continued to lose money over the next decade, and the only relief was when gas rationing during WWII encouraged people back to the ships for a short while. The war also caused a problem when the Greater Buffalo was requisitioned by the Navy and converted into a training aircraft carrier called the SS Sable. This gave the company untold logistical headaches, which were added to by union disputes and strikes.

The pleasure of a slow boat to your destination was being lost to a world that was looking for speed and convenience. Trains, aircraft, and cars improved and became mainstream modes of travel, and the old paddle steamers were a thing of the past. Not even their service as car transports could save them. A last-gasp attempt to convert the engines to oil did not stop the inevitable slide into obscurity for these graceful old ladies, and on May 9, 1951, they were officially taken out of service.

On June 21, 1956, the Greater Detroit was sold to Lake Shore Steel, Inc. and Siegel Iron & Metal Company. The owners of these two businesses were very sentimental about the Greater Detroit and were determined not to see it scrapped (even though both companies dealt in scrap metal), but the hard reality of economics eventually caught up with them, and the rocketing price of scrap metal finally tipped the scales. The public was invited to buy anything off the Greater Detroit that they could carry away, and soon they descended like a flock of vultures – everything not nailed down was carted off.

No one was interested in the vessel itself, so the decision was made to scrap it for the steel content of the hull. The easiest way to get back to just the steel was to set the ship alight and burn the wood and plaster superstructure off, leaving just the hull. So on December 12, 1956, the Greater Detroit was one of the ships towed out onto Lake St. Clair and set alight, Mail Online reported.

Read another story from us: The Fateful Journey of The Edmund Fitzgerald – A Great Lakes Disaster

Before she was towed out onto the lake, her anchor chains were cut, and the three-ton anchor was allowed to fall into the bottom of the Detroit River, as there was no steam power to raise it. The anchor lay on the bottom of the river until November 15, 2016, when it was recovered by the three divers and raised, once again see the light of day. The anchor will be refurbished and put on display outside the Detroit/Wayne County Port Authority. Writer: Cathy Buggs