Caroline Grabowski, a resident of Sault Ste. Marie in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, otherwise known as The Soo, has discovered a long forgotten potter’s field in the Soo Riverside Cemetery.

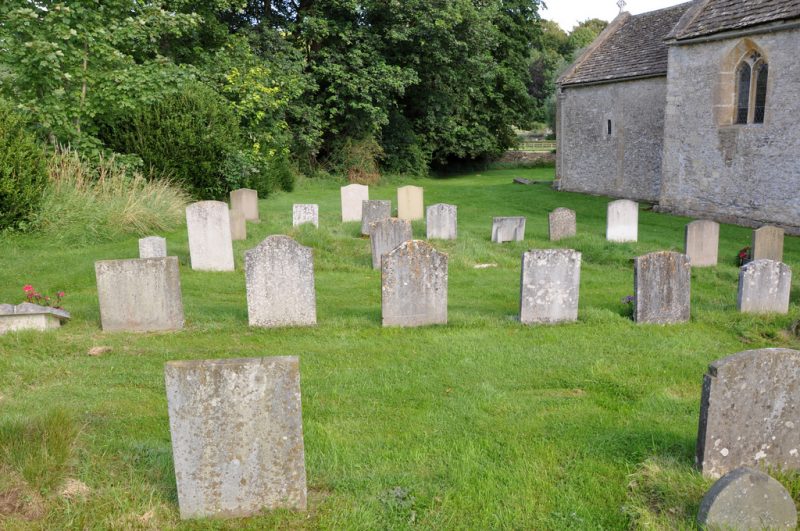

The cemetery never had any markers to show who was buried there or even that there had been a potter’s field on this overgrown patch of land. Grabowski is now making it her mission to share the information she has found as she pieces together the information on the souls buried there. A potter’s field is land that is unsuitable for the growing of crops and is traditionally used as the place for burying the poor or those unknown people who have no one to bury them. Nearly all cities have a potter’s field somewhere in the corner of a cemetery. The people were buried in the cheapest of wooden coffins and were stacked on top of each other – tightly, side by side in the ground. The unclaimed and homeless often ended up there, as well as widows and people who had been sent to workhouses.

Forgotten mass grave in the U.P. is rediscovered https://t.co/Rpk6LnMYw7

— Kristy (@BullyUzi) February 14, 2017

Today the bodies of the unclaimed are funded on a state level with grants paid to funeral homes who offer to dispose of unclaimed dead bodies. Just last year in Michigan, the state helped to fund the cremation or burial of 15,000 people at the cost of $260 per person, which means the funeral homes pay most of the considerable cost themselves.

Grabowski has led tours of local cemeteries for many years and is the president of the Chippewa County Historical Society. She considers the dead to be a part of the rich history of a town or area, telling of how dangerous certain jobs were and disclosing the economic welfare of the area over time. She became interested in the potter’s field when she was researching local cemeteries and kept seeing the letters “pf” beside burial records. She searched through birth, death, and marriage records. She hunted through newspapers as far back as she could and found the most surprising details recorded. There was little political correctness back in the old days, and they included in public records such things as a husband being a wife beater.

Newspapers had wonderful, colorful articles that summed up events and attitudes of the times, like potter’s field resident Martin Olson, who died in a saloon fire because he was too drunk to find his way out. The firemen were quoted as saying that he even looked drunk when he was found burned to a crisp. Some of the dead in the field died while working. Everette Sellender accidentally blew himself up with dynamite and Laughlin McDonald was crushed when a tree fell on him.

Some, sadly, escaped their hard life by suicide, such as Riley Johnson and Charles Edwards. Others left no story behind, just a name and a date. A Mrs. Miller died in 1896 and Henry Henderson passed away in 1905 – there is no record of how these souls passed on. There is yet another group of the dead – those who had no names at all to record and were only memorialized by a sentence or a few words, such as a corpse found at a hotel, and a strangled baby. In this area there had been many immigrants, all hoping to earn enough to make a new life or to send some money home. Some of these, too, were buried in the potter’s field, having no family to bury them in the strange new land, Detroit Free Press reported.

Grabowski’s efforts are sparking interest in other potter’s fields, and other researchers are joining with her to give the dead a voice so people may know their stories. None of the people buried in the Soo Riverside Cemetery potter’s field can be given headstones as there is no record of where each is buried.

So a simple idea was acted upon and now there is a small sign that lists those who are buried there. Grabowski has listed Jessie Sutherland, a victim of heart disease, who was buried there at an unknown age, and Annie Hendereckson, who was killed by her husband, who could not bury her because he was in jail. These and many others, 281 in total, rest in peace in a place that is now no longer a forgotten piece of history but a place of remembrance and respect, where their names can be recalled and, for some, their life stories shared.