Literature geeks know that the early version of Beauty and the Beast was penned by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve. The French author had it published in 1740, and her story had everything: elaborate subplots that allow in-depth analysis of characters; magical items such as a ring capable of transporting the protagonist to a certain place; characters such as those of the jealous sisters; as well as some societal themes, that the narrative hints at how women had their marriages arranged in the past.

While fairy tales such as Beauty and the Beast can be traced back to as many as 4,000 years ago–the BBC reported in 2016 on research done by scholars at Durham and Lisbon universities that confirm such claims–it was Madame de Villeneuve’s version that triggered others to adapt, rework, retell and help Beauty and Beast become two of the world’s most beloved protagonists today.

The latest film version of the story, starring Emma Watson and Dan Stevens, a box office success of 2017, is just the latest of numerous adaptations. We thought you might find it amusing to know how the original storyline went…

In the 1740 narration of the story, Beauty has five siblings, three brothers and two sisters, and all of them are children of a wealthy widowed merchant. Beauty is the youngest of all six. As it is in later adaptations of the story, her character is attractive. She is the humble one, pure at heart, beautiful and well-read. Her sisters are also beautiful, but they are wicked, spoiled and would do anything to just mistreat and hurt Beauty.

Things take a turn for the worse among the family when the father loses all wealth. His fleet of trade vessels is lost to a storm and the family lives in poverty for the next several years. However, one day, hopes are up as word arrives that there is still one ship from the lost fleet that survived. Its cargo has been saved too. The father, confident that he will regain some money, prepares to go and acquire the cargo.

When he checks with his sons and daughters whether they want anything as a gift, only Beauty remains modest. She doesn’t want any fine or expensive things like her sisters and brothers. All she wants is a rose, a flower said to grow elsewhere but not where they live.

The joy that at least one ship has returned would evaporate all too soon, however. The cargo gets seized as the family is buried with debts. On the way back home, the father, disappointed and virtually penniless, gets caught in a storm. He manages to find refuge in a strange place, a palace where the host does not present himself, yet where he is provided help and hospitality.

As the father leaves the property the following day, he notices a dazzling rose garden in the yard, and he takes one flower for his youngest daughter. Which is when the ghastly owner of the property appears: the Beast, angry because the guest he accommodated so well the previous night now broke the code of hospitality. Namely, the unfortunate father had picked the most alluring rose of all, at the same time the most-treasured commodity found at the Beast’s property.

What happens next is that the father needs to be punished, but he obtains his freedoms as he arranges one of the daughters to go and live with the Beast. It is Beauty who gets chosen to live with the Beast until the end of times. For some critics, it is this specific episode that speaks volumes about how women were prepared for arranged marriage back then.

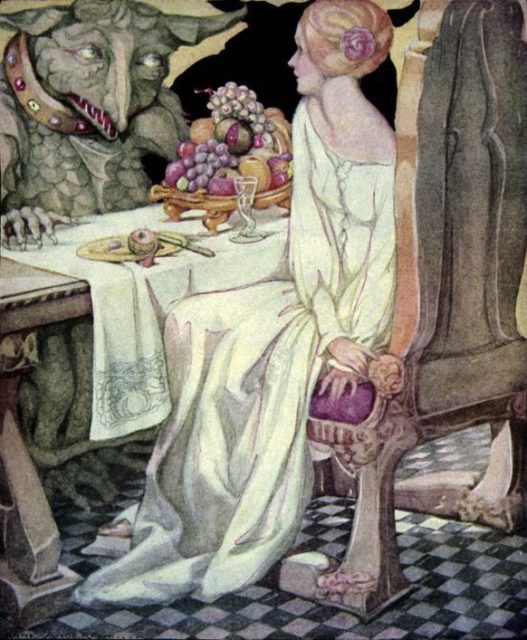

Beauty indeed goes to the palace. There, she is treated more or less like a princess. While it is a story with a presumably happy ending, there are a few obstacles until the reader gets there. In the beginning, at the end of each day, the Beast continually proposes marriage, to which the young lady remains persistent with her negative answer. However, each night, Beauty also dreams of the prince charming, the love of her life. Little does she realize, there is a prince already very close to her.

Simultaneously, the Beast is also faced with challenges on his own. Presumably, he is yet to learn how to truly express his emotions and desires, if he wants to grow into the person worth Beauty’s love. He is also referred to as “bête” in the story, a French word that carries the meaning of “beast,” as well as “being unintelligent.”

In a culmination of the story, one day Beauty negotiates with the Beast to visit her father and siblings. The Beast approves the idea only if she is to return to the palace on a certain day, and that she takes two enchanted items. The first is a mirror that can instantly show what is happening at the palace at any moment. The second, the ring, which, quite symbolically, has the power to instantly transfer Beauty back to the Beast.

In probably the most famous recounting of the story, in Disney’s animated 1991 version, the negative character is someone like Gaston, arrogant and nowhere near close to Beauty’s charisma. But the weight of being negative in Madame De Villeneuve’s narrative falls on the elder sisters. They have only sinister intentions toward Beauty, so they persuade her to stay home for a longer time than initially agreed with the Beast.

Already on the first day of her extended stay, Beauty is to nearly regret her decision. As she takes the mirror to check what is going on at the palace, the sight of Beast’s almost lifeless body, lying in the garden very close to where Beauty’s father had initially picked a rose, prompts the young lady to use the ring. It is in this moment of reunion that Beast finally regains his human identity, “the prince of dreams,” and as you already know, the pair indeed lived happily ever after.

Later versions of Beauty and the Beast were usually shortened, and some became way more popular than Madame De Villeneuve’s original. Such is the case with Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, whose write up of the tale was out by 1756 and gained far greater momentum than that of de Villeneuve.

For instance, de Beaumont’s version shows a different angle of how Beauty becomes the daughter of a merchant. Initially, she is born to a monarch and a fairy, and she suffers because she is the child of a forbidden relationship. The main male protagonist, a young prince, is again the victim of dark magic. He is turned into a beast, and he is to regain his human shape only once he marries somebody who knows nothing of his past and real human nature.

Unfairly, Madame de Beaumont does not give any credit to Madame De Villeneuve as the first writer of the story. As it turned out, her abridged version was more poular, which consequently led to plenty more adoptions that were produced from the 18th century onward.