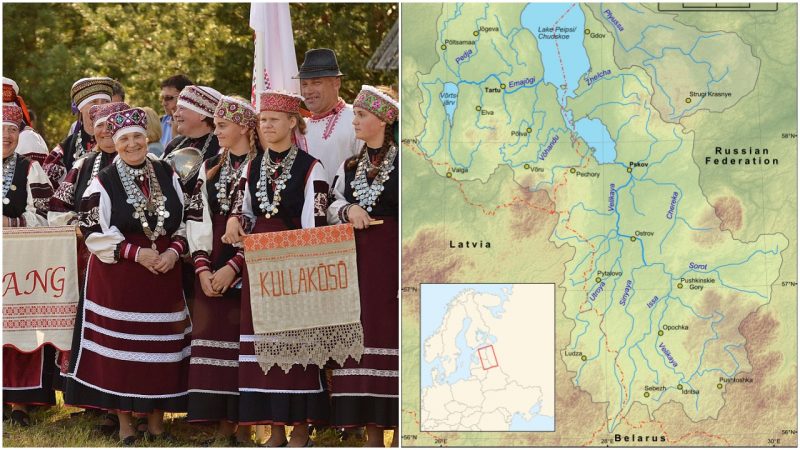

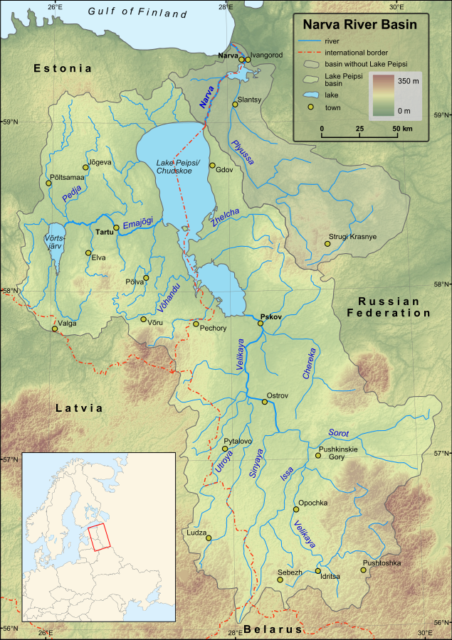

The Setos are an indigenous ethnic and linguistic minority people, most of them living in the Setomaa region, nestled between the southeast of Estonia and the northwest Pskov Oblast of the vast Russian federation.

It seems that since time began, the Setos people have been surrounded by many nations, which has affected their culture. However, these people have fiercely struggled to preserve their ancient customs and beliefs, despite converting to Orthodox Christianity as an ethnic group. They speak the Seto language, supposedly a dialect of the South Estonian or Võro language. This language, just like Finnish and Estonian, is part of the Finnic group within the Uralic family of languages. Accounts suggest that the number of Seto people around the world is approximately 15,000.

Before 600 AD, the entire Setomaa belonged to the northern Finnic lands of the indigenous Uralic peoples. After that, the Slavic tribes commenced their migration northeast, and into the Uralic territory. During this migration, both Slavic and Finnic tribes mingled together.

Most likely the first important event that distinguished the Setos from others was the forced conversion of the Estonians to Catholicism during the 13th century. At this point, some Setos reportedly remained as pagans. It was in the 15th century when the indigenous community converted to Orthodox Christianity. Despite that, they still preserve their ancient cultural beliefs.

The border that changed it all

In 1920, the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed, a historic event that is regarded as the “birth certificate” of the Republic of Estonia; in other words, the very first “de jure” recognition of the small Baltic country. Following WWII, Estonia was annexed by the Soviet Union. Then, in the years after the war, the authorities in Moscow revised the border between the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. Moreover, “the border,” slowly but steadily, started to gain significance among the indigenous Setos people.

Throughout the 20th century, the border shifted on multiple occasions. However, once the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, and Estonia established its own national borders, the region of Setomaa faced a division between the two countries. This happened for the first time in history and posed a threat to the Setos.

The culture of the Setos developed throughout the 20th-century, and especially thriving in the early decades. With Estonia gaining independence, the country underwent “Estonification,” which caused the Setos to diminish as a distinguishable entity. The Setos population decreased too on the other side of the border, in Russia. Despite the Russian-Estonian border not being ratified in the region of Setomaa, it still divided the area into Russian and Estonian. The Setos found themselves in the midst of the turbulence. The border started to divide them from one another, splitting their fields, cemeteries or churches. So, here is what happened next.

Elena Nikiforova, a researcher at the Center for Independent Social Research in St. Petersburg, undertook field work in Setomaa as the border was enforced.

She has stated: “The border came, and it broke their daily life. The border became this trigger for them to start thinking of themselves as a separate people. Being divided by the border, they became united.”

From the entire chaos of the Soviet Union’s collapse, the Setos emerged, declaring themselves as constituting a kingdom of their own back in 1994. Within their kingdom, they have preserved their ancient beliefs, but they have also embarked on a journey to give a modern look to their identity by founding new traditions.

“Unable to alter the course of foreign policy and torn between two countries, the Setos in 1994 declared for themselves a new, unified entity: the Kingdom of Setomaa. Now, more than two decades later, they are keeping that kingdom alive.” reports The National Geographic as well.

As the Seto people visit church today, they do not forget to pay their respects to their own earth-gods. One of these is the grain god Peko, who is always revered. Reportedly, since the fall of the Soviet Union, Peko is also considered the king of the Setos and is believed to be resting in the caves under a church in Pechory, on the Russian side.

According to local belief, the god will awake only if there is a great danger threatening the Seto people. This is just one example that illustrates the impressive worldview of the Seto people, where older religious rites thrive next to those of Christianity. They also have an anthem of their own.

“Setomaa with its culture is like a buffer area between Eastern and Western nations. This situation is also described by the Seto anthem: it is difficult to create a home on the edge of two worlds (Kül’ oll rassõ koto tetä’ katõ ilma veere pääl),” further says the Visit Setomaa web page.

Each year, the Seto also choose a so-called steward of the king, to serve the Kingdom of Setomaa. The event is followed by an annual celebration of the Day of the Kingdom (Seto Kuningriigi päiv). It is a prestigious local festival, in which the larger Seto villages rotate as hosts of the event. The office is highly ceremonial and has been so far handled by various local activists, scholars or politicians.

In these times of change, many young Seto people have left Setomaa in order to live and work in other parts of the world. Many of them do not return to live in their own kingdom.

Read another story from us: Rare photos of indigenous Sami people of The Nordic Areas

It is a question for the future to see what the destiny of this indigenous people brings, whether they perish or thrive living on the borderline.