Dr. Robert Hooke was a genius; and if there is another word that describes someone as being above genius, it would be a title that belongs to Dr. Hooke.

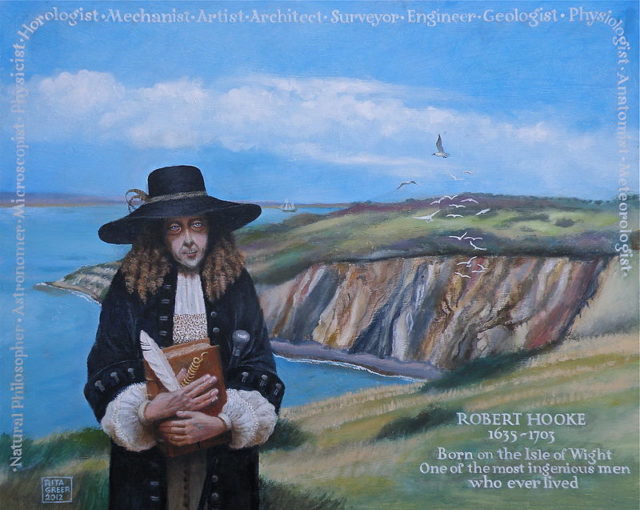

He was an English polymath, natural philosopher, and an architect born on the Isle of Wight in 1635. Called “England’s Leonardo,” Hooke was simultaneously Surveyor to the City of London after the Great Fire of London, Gresham Professor of Geometry, and the curator of experiments at the Royal Society. And that’s not all folks.

Hooke was a sickly child who spent most of his time in bed. But that didn’t prevent him from expressing his beautiful mind in all the ways he could. While lying in bed, Robert started drawing from his imagination. His father was a clergyman and declared his son’s painting were not the simple childish art of a young boy, but the work of a genius. When he was 13-years-old, Robert’s father died leaving his boy £40, which was a substantial sum at the time.

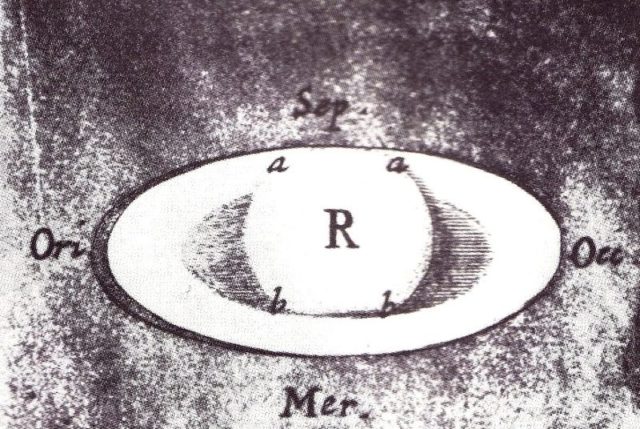

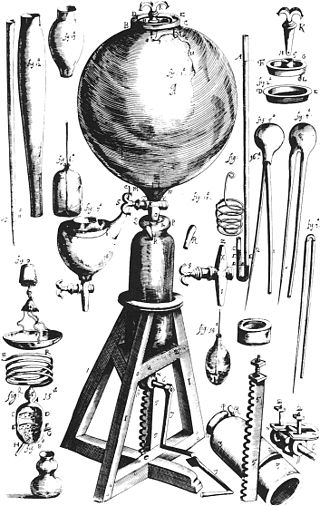

Robert studied at Westminster School in London, where he excelled in mechanics, mathematics, and languages. In 1653, at the age of eighteen, he enrolled at Christ Church College at Oxford University where he focused on science. Hooke was building telescopes that would satisfy his curiosity in observing the orbit of Mars and the gas giant Jupiter. When he became interested in the theories of evolution, Hooke studied fossils and invented the modern microscope.

He was only 27 when he became curator of experiments for the Royal Society. By the age of 30, Hooke dedicated himself almost entirely to biology, making ever finer microscopes so that he could observe the structure of living beings.

By 1665, as his microscopes improved, observing slices of cork bark, Hooke came to the conclusion that they are made up of tiny square segments that he called “cells” because they reminded him of monks cloisters. And hence the word “cells” in biological terms was first used.

Following his discoveries, Hooke published his work “Micrographia,” which is one of the greatest books of all time, illustrated by the genius himself.

His studies of the invisible world were made public and thus visible to the world; it is needless to say that the book shook the world of science.

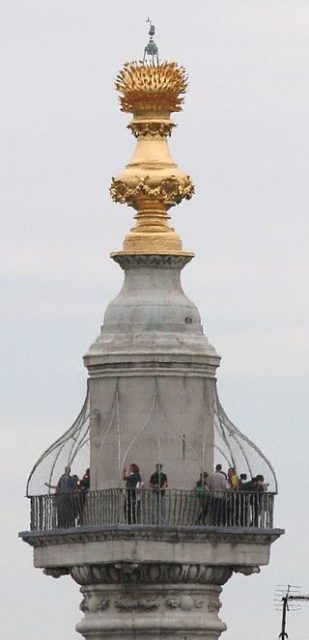

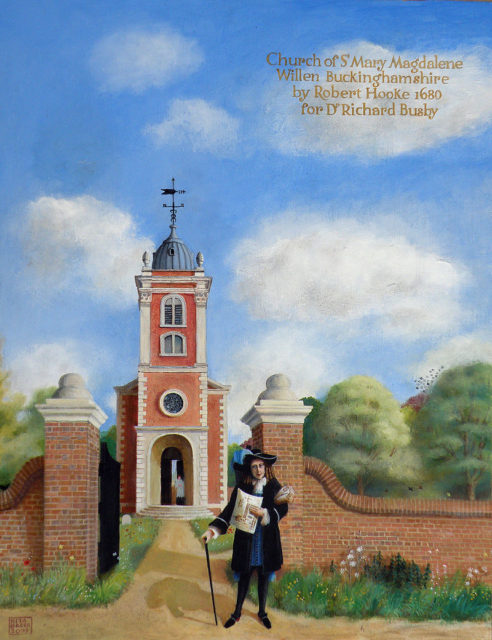

In 1666, the Great Fire of London destroyed the city, burning down 13,200 houses and 87 churches. However, out of the ashes, a new city was born which is today one of the greatest in the world. Hooke was one of the architects that proposed a new building plan for the city, but he got to design the Monument to the Great Fire of London together with Christopher Wren. The monument was an initiative of Charles II, and it was erected near Pudding Lane. 200 feet (61 meters) tall, it took Wren and Hook six years to complete it. The monument is still the world’s tallest freestanding stone column.

In the meantime, Hooke was investigating the phenomenon of refraction, deducing the wave theory of light. He was the first scientist ever to suggest that the air is composed of small particles which are separated by relatively large distances. He was also the first one to put forward the idea that matter expands when heated. Oh, and it wasn’t like he ignored geography either – he did some pioneering work in surveying and map-creating, taking part in a project that led to the first modern plan-form map.

Hooke discovered the law of elasticity which he first published in 1660 as an anagram “ceiiinosssttuv.” He published the solution in 1667 as “Ut tensio, sic vis” meaning “As the extension, so the force.” He practiced his law on elasticity in his development of the balance spring, or hairspring, which made possible a portable timepiece for the first time – the watch. Hooke almost preceded Newton in the theory of gravity. At least, he was the first one who hypothesized that gravity follows an inverse square law.

Hooke made incredible achievements in the fields of astronomy, biology, microscopy, horology, gravitation, paleontology, and architecture. Whatever he became interested in, he made discoveries that nobody before him had.

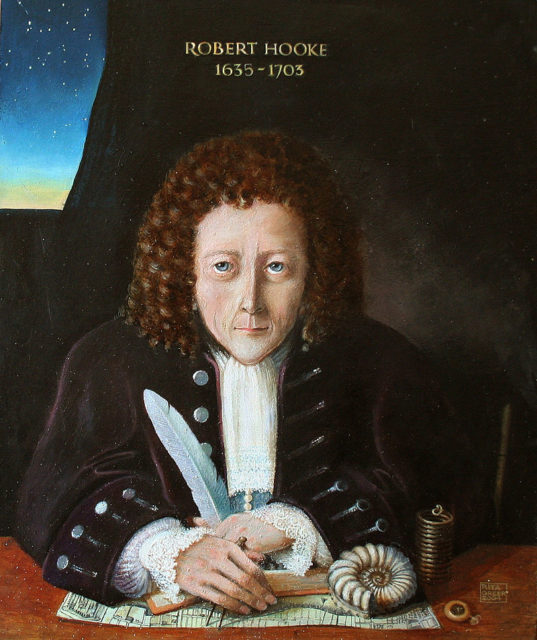

No authenticated portrait of Robert Hooke exists. The first was recorded by his close friend John Aubrey, who described Hooke in middle age and at the height of his creative powers: “He is but of middling stature, somewhat crooked, pale-faced, and his face but little below, but his head is large, his eye full and popping, and not quick; a grey eye. He has a delicate head of hair, brown, and of excellent moist curls. He is and ever was temperate and moderate in diet, etc.”

The second is a rather unflattering description of Hooke as an old man, written by Richard Waller: “As to his Person he was but despicable, being very crooked, tho’ I have heard from himself, and others, that he was straight till about 16 Years of Age when he first grew awry, by frequent practicing, with a Turn-Lath … He was always very pale and lean, and latterly nothing but Skin and Bone, with a Meagre Aspect, his Eyes grey and full, with a sharp ingenious Look whilst younger; his nose but thin, of a moderate height and length; his Mouth meanly wide, and upper lip thin; his Chin sharp, and Forehead large; his Head of a middle size. He wore his Hair of a dark Brown color, very long and hung neglected over his Face uncut and lank…” From the biography of Robert Hooke written by Allan Chapman: “England’s Leonardo: Robert Hooke (1635–1703) and the art of experiment in Restoration England.”