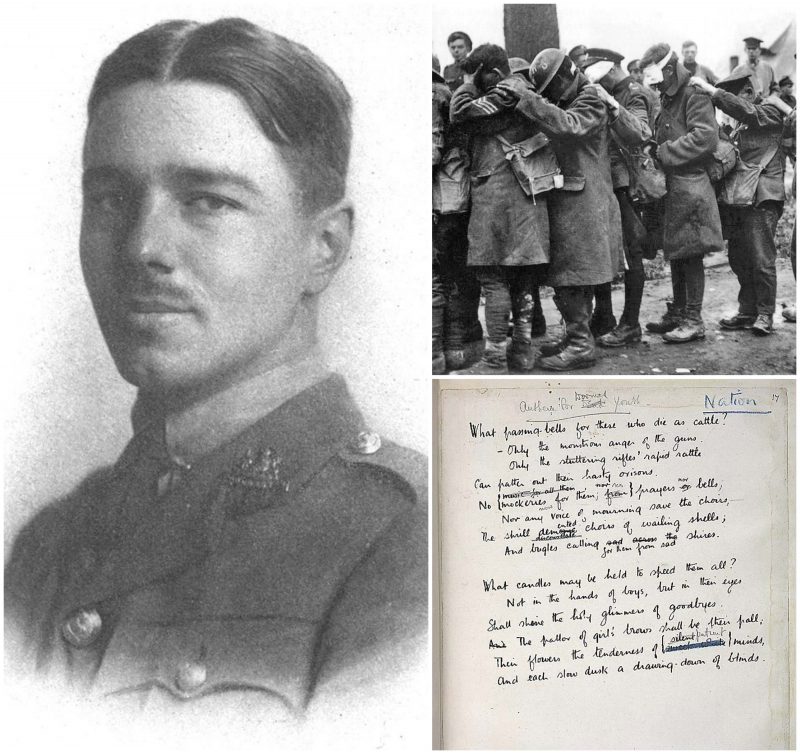

Wilfred Owen undoubtedly wrote some of the most awe-inspiring British war poetry of World War I.

Rare are those who have not heard of ‘Dulce et Decorum Est,’ his most popular poem. There is a slight notion of mystic symbolism, as Owen fully grasps the harsh reality of warfare and effortlessly expresses the carnage on paper.

The intense experience of WWI is reflected in his poems. Literary depictions of relentless trauma and inhumanity, all of which were written in a period of just over a year.

He was born in Oswestry, Shropshire. After finishing school, he worked as a teacher’s assistant and then as a private language tutor in France in 1912. An admirer of Shelley’s and Keats’ work, the 19-year-old Owen took much pleasure in reading.

While Owen was working as a tutor in France, the First World War broke out. Completely disconnected from the ongoing war, he didn’t feel as if he was a part of the political conflict, despite seeing the horrors of war as countless wounded soldiers ended up in hospitals.

Little did he know that he would eventually become involved and succumb to his fate. Pressured and feeling guilty after reading one too many Daily Mail newspapers sent by his mother, whom he was deeply attached to, he returned to England to volunteer on 21 October 1915.

He was trained in England and proudly enlisted as a second lieutenant in the “Artists’ Rifles group.” The enthusiastic young Owen with a boyish vigor enjoyed the impression he made on the people who saw him in public with the soldier’s uniform.

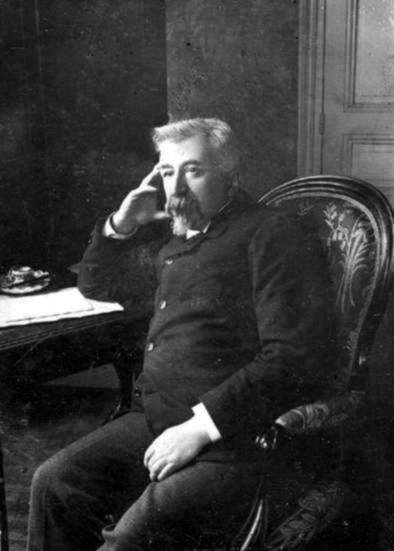

Owen was sent into battle on the last day of 1916, in France, and during the first week, he was half-sleeping yards away from a heavy machine gun. His childish spirit quickly dropped after being in the trenches for the first time, experiencing blinding gas assaults, sleeping in frost during the winter, and smelling the rotting stench of his fallen comrades.

His 664 letters to his mother, all of which were kept by her, clearly reveal his experiences from the war. Owen comes clean with the unforgiving consequences of shellshock in a letter to his mother:

“I can see no excuse for deceiving you about these last four days. I have suffered seventh hell. – I have not been at the front. – I have been in front of it. – I held an advanced post, that is, a “dug-out” in the middle of No Man’s Land. We had a march of three miles over shelled road, then nearly three along a flooded trench. After that, we came to where the trenches had been blown flat out and had to go over the top. It was, of course, dark, too dark, and the ground was not mud, not sloppy mud, but an octopus of sucking clay, three, four, and five feet deep, relieved only by craters full of water…”

He was away from heavy fighting at the beginning but went on to see a good deal of combat on the front line, and he experienced heavy explosions, various injuries, concussions, and a very nasty case of shell-shock, which is clearly reflected in his style.

Of all the atrocities Owen endured, the ordeal of being trapped in a shell-hole and bombed for three days, under the corpse of a fellow officer, proved to be the absolute worst. He was diagnosed with suffering from shell-shock. The experience saw a merciless, yet true expression in his poetry.

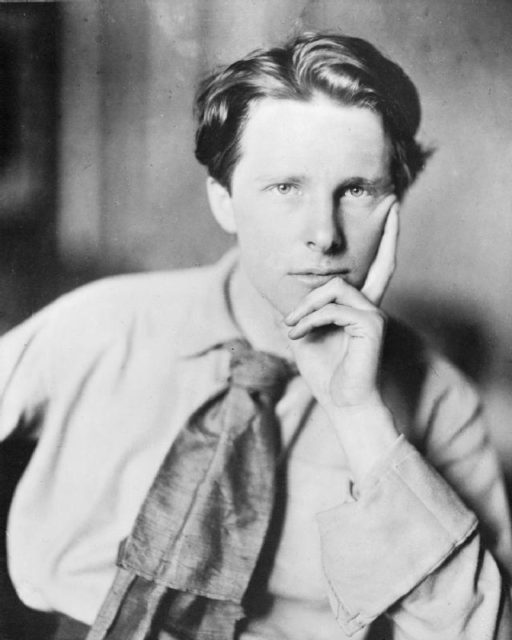

Deeply affected from the heavy shell-shock, he was sent to the psychiatric hospital in Edinburgh, Craiglockhart. There he met the similar-minded Siegfried Sassoon, a soldier, and poet himself, who greatly inspired and supported Owen’s war poetry.

Sassoon was a highly decorated soldier for his bravery on the Western Front, as well as being one of the top leading poets of WWI. His poetry described and sharply satirized the war and its many pretentious patriots.

Sassoon introduced Owen to the works of prominent literary geniuses like Robert Graves and H. G. Wells. The fellow soldier-poet would leave a huge impact upon Owen’s life and views.

Owen returned to France and was re-sent to the trenches in August 1918, despite Sassoon’s desperate pleas for him to refrain from fighting in the war.

For the display of bravery in seizing a machine-gun from the German’s hands and using their own weapon against them was awarded the Military Cross in October 1918. He was perhaps inspired by the excellent example of courage shown by his battle-worn friend Sassoon.

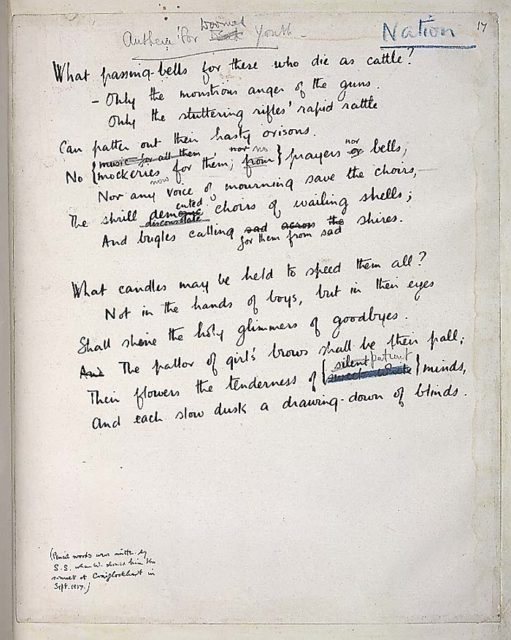

It was from August 1917 to September 1918 that the soldier-poet had his most prolific period and wrote his most famous poems. “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” “Futility,” “Strange Meeting,” and “Dulce et Decorum Est” which strongly disapproves and condemns the war, remain a poetic landmark.

Strong depictions of WWI warfare and the landscape of the human psyche among the trenches are flawlessly mirrored in his works. The structure can be compared to the great poet, Rupert Brooke.

Wilfred Owen was killed on 4 November 1918, a week before the war ended. He was leading his men across the Sambre canal at Ors when he was shot.

The terrible news reached his friends and family on Armistice Day, 11 November. After hearing of his death, his good friend Sassoon fell into a deep depression and could not accept his passing for years.

Five of Owen’s poems were published during his lifetime. A volume of poems which include the prominent poems written by him is edited by none other than Sassoon. It was published in 1920.

Undoubtedly, Wilfred Owen was an English soldier and poet who brilliantly channeled his fury and reproach of the human atrocities of the war he knew so well.

In posthumous praise of Owen, Geoff Dyer said:

“To a nation stunned by grief, the prophetic lag of posthumous publication made it seem that Owen was speaking from the other side of the grave. Memorials were one sign of the shadow cast by the dead over England in the twenties; another was a surge of interest in spiritualism. Owen was the medium through whom the missing spoke.”