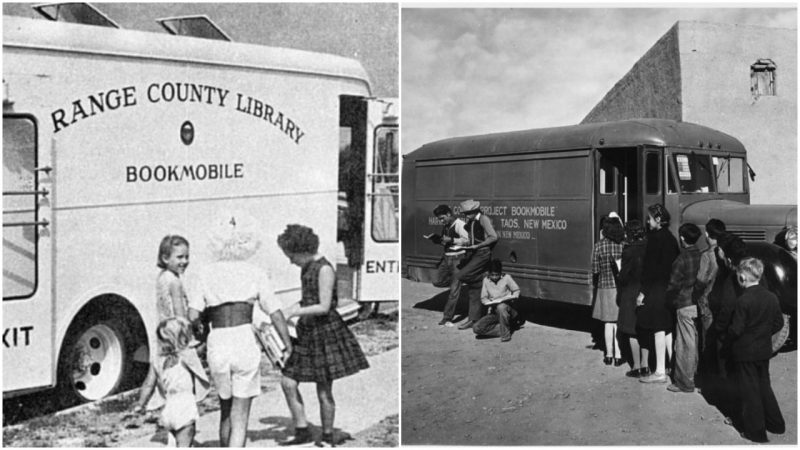

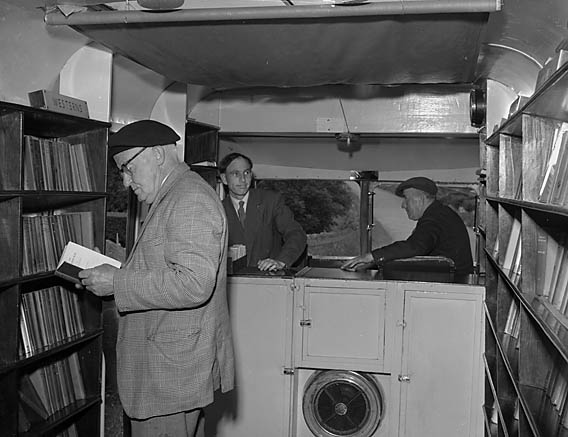

The bookmobile’s design is such that once parked, readers could easily access its treasured literary items. Now it’s more like a thing of the past, but back in the day, this way of distributing literature to people functioned perfectly.

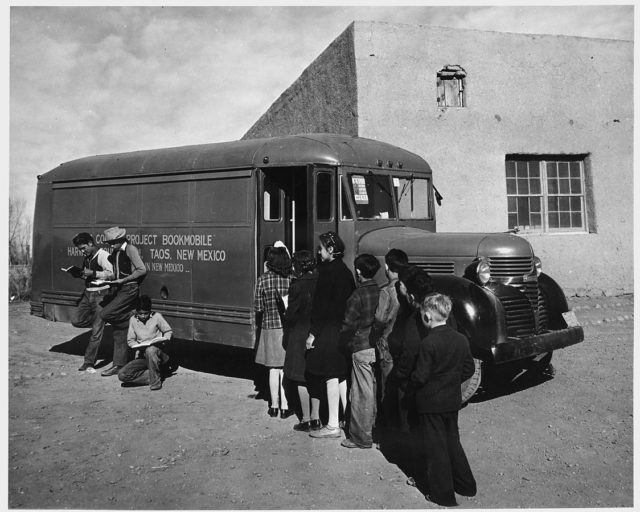

It was working exceptionally well in remote areas such as villages or suburbia – places that otherwise did not have an access to a nearby library.

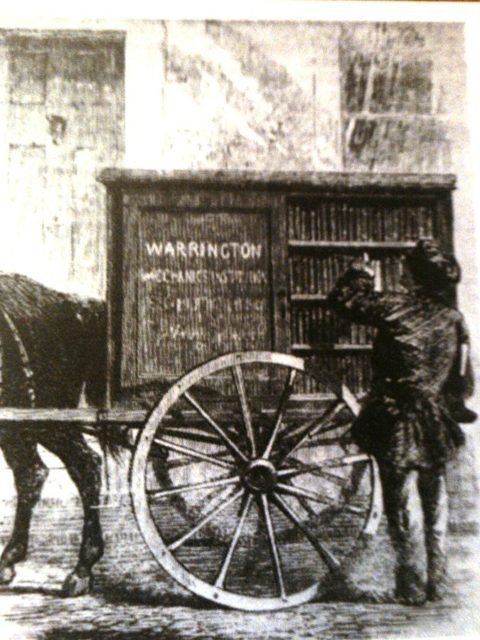

Bookmobiles saw their heyday in the mid-twentieth century, however, their story begins most likely somewhere in the late 19th century. In 1857, an English periodical dedicated to the industrial classes, entitled as “The British Workman” had reported about a perambulating library that operated in the circuit of eight villages in Cumbria, in the northwest of England. According to the news story, it was a Victorian merchant and philanthropist, George Moore, who had launched an action to “diffuse good literature among the rural population.”

On the other side of the ocean, one of the first bookmobile operating were reported in Fairfax County, Virginia, as early as 1890. The bookmobile services had started out in the northwestern part of the county, but a county-wide service followed only a few decades later, in 1940. The county-wide action was initially helped by a truck loaned by the Work Progress Administration (WPA).

An early bookmobile in the States is further reported in 1904 by the People’s Free Library of Chester County, South Carolina. This one served to rural areas and had a mule-drawn wagon that carried wooden boxes of books. Worth to mention, in those days, the bookmobiles were known as book wagons.

One more early American bookmobile was initiated by Mary Lemist Titcomb (1857 – 1932), a librarian who worked at the Washington County Maryland Free Library. Allegedly, Titcomb started out the bookmobile services after expressing personal concerns that the library did not have a satisfactory reach to all the people possible. Thanks to Titcomb’s efforts, by 1905, the Washington library topped the list of first institutions that provided American book wagons to its citizens. The vehicle even took books straight to the homes in the most remote parts of the country.

Sarah Byrd Askew was a pioneering public librarian who was also among the first initiators of the bookmobile. Reportedly, she personally drove a Ford Model T packed with books to rural areas in New Jersey, as early as 1920. Then in 1923, it was the Hennepin County Public Library of Minneapolis that followed with bookmobile services. Services in Kentucky and nearby Appalachia that dealt with bringing books to those unable to make it to the library were reported in both the 1930s and the 1940s.

However, the real boom for bookmobiles was most likely throughout the 1950s. Thanks to the Library Services Act of 1965, the bookmobile services rapidly spread and reportedly reached more than 30 million people across diverse rural communities.

An additional legislation of the 1960s that provided more government funding, renewed the popularity of bookmobiles. For example, the “Library in Action” was a late 1960s Bronx program that aimed to supply books to youths in underserved neighborhoods. The rising fuel costs and budget cutbacks that followed in the proceeding decades, unfortunately, pushed libraries to scale back the bookmobile services.

Read another story from us: Bookworm pays $1550 late fees for library books taken out in 1970s

As of more recent times, there has been a 20 percent decline reported in bookmobiles in the years between 1990 and 2003. Nevertheless, the digital revolution of the 21st century and the availability of many books online just may be a good reason why bookmobiles are now thing of the past. Despite that, at current, some bookmobiles still function well, especially in developing parts of the world, fulfilling their initial purpose – to bring the books to some of the most remote places around.