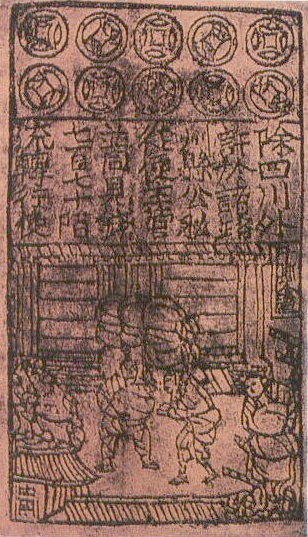

The Shang Dynasty copper coin, the first example of which was found in a tomb, is the earliest known practical currency and dates from the 11th century BCE.

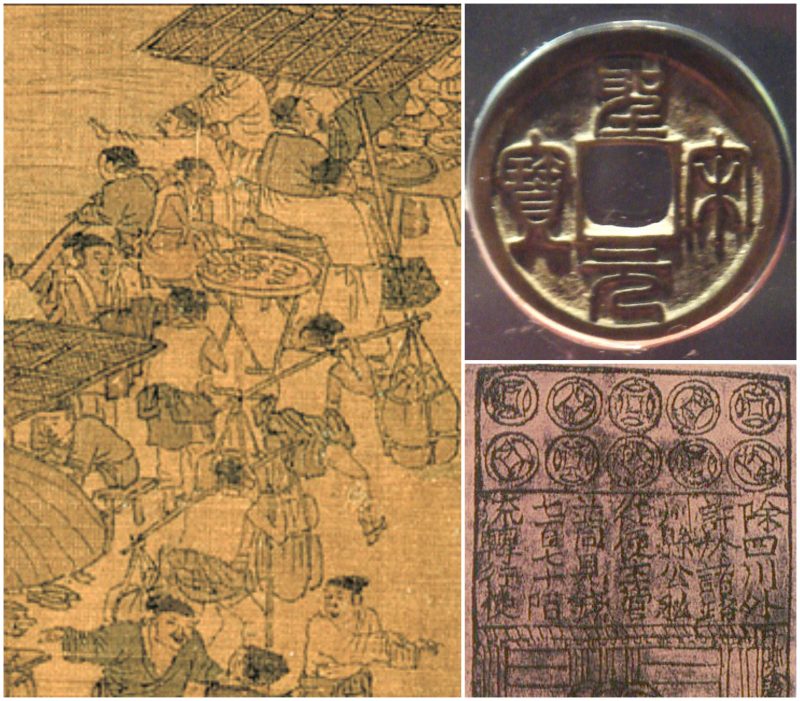

The square-holed metal coins, which are easier to handle by the use of strings, were deemed a standard trade currency. Whether they were made from silver or gold, the durability of the coins meant they lasted, as well as their effectiveness against counterfeiters. But there is just one problem – a rich man in this era would have had to use many donkeys and wooden carts in order to carry the heavy burden of metal coins.

This is where “Jiaozi” comes in. Because of safety reasons and the need to keep a watchful eye on economic accounts during the Song Dynasty, the Chinese government licensed special trade deposits for the people’s coins.

People would deposit their coins in these units and be given special paper notes. Seeing that this method was quite efficient, the government began issuing the notes as a legal currency for trade. Thus, the world’s first official paper money saw the light of day.

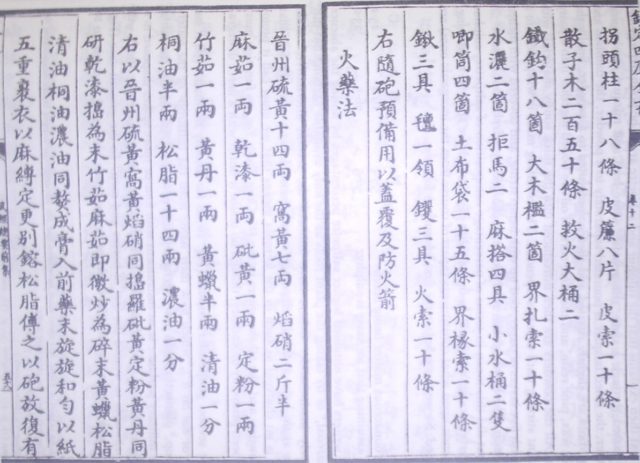

An alternative form of currency which surpasses the square-holed coin’s practical use, it first appeared in the Sichuan capital of Chengdu in the 10th century. Regarded as the first ever paper money, it reflects China’s great economic progress in the Song Dynasty (not to be confused with the Shang Dynasty).

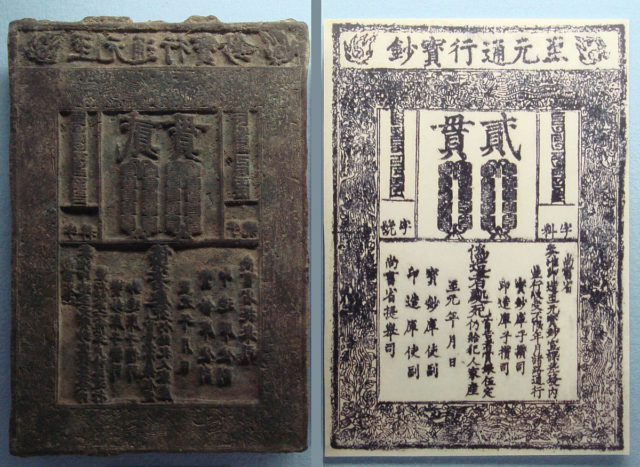

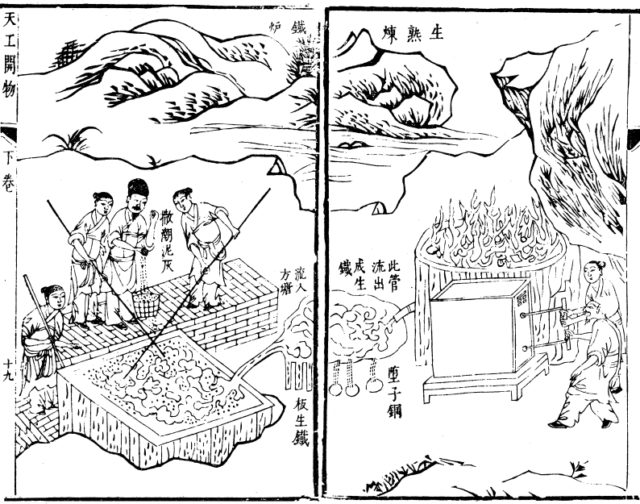

Many printing factories were equipped with special woodblocks and six colors of ink. The factories were located in four different areas of China – Chengdu, Anqi, Hangzhou, and Huizhou.

The pictures and symbols on the paper were in honor of the Emperor, other key persons, and landscape depictions of the Song Dynasty.

In order to discourage sneaky counterfeiting, the government used special colors from different plants and fibers. The early paper notes were very fragile and expired after three years, therefore, they were only to be used in some regions of the empire.

Even though the metal coins were harder to counterfeit than paper, jiaozi notes were stamped with multiple banknote seals, which was more tricky to counterfeit.

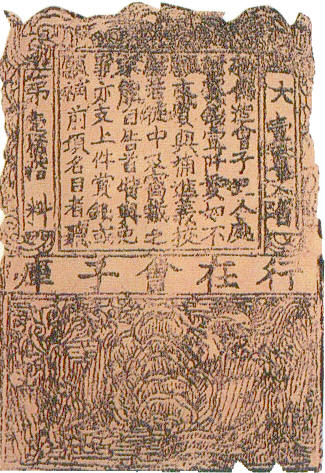

Reportedly, there were labels on the paper money which warned and threatened would-be counterfeiters. Whoever tried any funny stuff would be decapitated and the witness rewarded with a hefty sum.

The jiaozi money was printed as single standard and was legitimate in every part of the empire in 1265. They were also economically backed by silver and gold, and available in 1 and 100 strings of coin denominations.

Sadly, with the conquest of the mighty Mongols in 1279, the currency failed, lasting only 9 years. The Yuan Dynasty, founded by Kublai Khan, favored the innovative currency and began issuing their own paper money – “chao”.

Fascinated by the innovative idea of government-backed currency, Marco Polo himself introduced the new money back in Europe, when he returned from his visit with Kublai Khan.

The Yuan Dynasty’s reign was short and came to an end in 1368. Due to the uncontrolled increase of the currency’s printing, as well as the fact that the paper money was not backed by gold or silver, the dynasty suffered inflation and economic issues.

The Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644) which favored silver as the standard currency, was also noted for printing paper money, but it was stopped in 1450. It was not until near the end of the 19th century that China restarted printing the yuan during the Qing Dynasty.