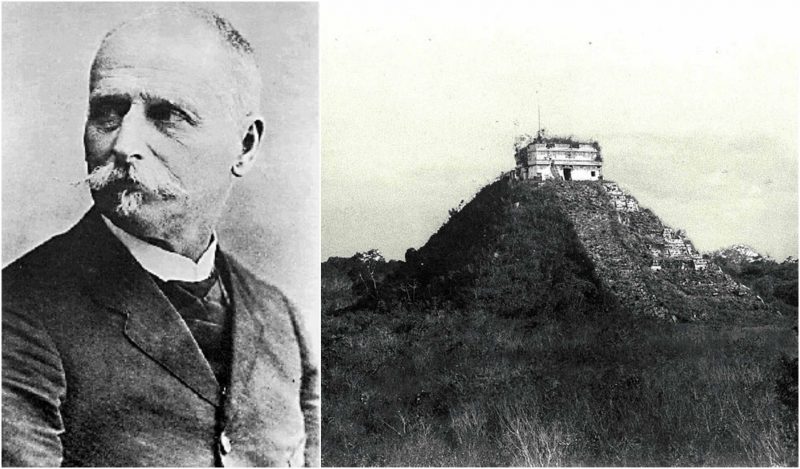

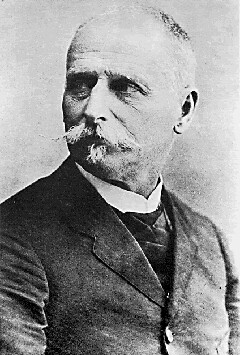

Teobert Maler, later known as Teoberto, was a German adventurer fond of photography.

There is nothing extraordinary in his interests except that he dedicated his life on documenting the ruins of the Maya civilization and made a big contribution to the body of knowledge concerning the Mesoamerican culture.

Maler’s father was a German diplomat for the Duchy of Baden and was serving in Rome when Teobert was born in 1842. Teobert studied engineering and architecture in Karlsruhe and moved to Vienna when he was 21 to work for the famous Austrian architect and professor, Heinrich von Ferstel. After a few years, the young Maler was granted Austrian citizenship.

Curious about the world, Maler traveled to Mexico, joining Emperor Maximilian’s army as a soldier. Very soon, he rose from Cadet to Captain. After the surrendering to the Mexican Republican forces, Maler chose to stay in Mexico instead of returning to Europe. He later became a Mexican citizen and changed his name to “Teoberto” because it was easier to pronounce in Spanish.

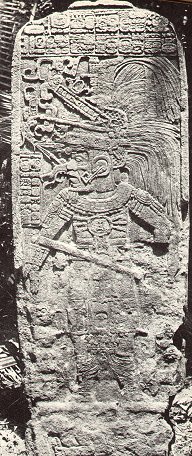

While in Mexico, Maler became interested in Mesoamerican antiquities and as well as photography. In 1876, he visited the most important archeological site of the Zapotec culture, Mitla, in the state of Oaxaca, and took detailed photos of its structures. The following summer he moved to San Cristóbal de las Casas and visited the ruins of the Maya city-state of Palenque. Although the site was already known, it hadn’t been explored in depth, so when Maler went there, he had to employ a group of local Indios to open up a path to the site using machetes.

In the week he spent at Palenque, Maler measured, sketched, and photographed the site, realizing that the previously published information about it was inadequate and that most of it depicted only a limited portion of the buildings. While he was at Palenque, another adventurer visited the site, the Swiss botanist Gustave Bernoulli, who shared the same passion for the Mayan culture and sites as Maler.

In 1878, Maler returned to Paris as he had to deal his father’s estate which was in legal difficulties. While there, Maler hired lawyers to sort it out, and he spent his time giving lectures on Mexican antiquities. In his free time, he dug out all the possible documents he could find on Mesoamerica. After six years, in 1884, the estate was finally settled, and Maler, with his small inheritance, returned to Mexico to devote himself fully to the study of his passion – the Mayan culture.

Maler settled in a small house in the town of Ticul, in Yucatán. In his new home, he set up a small photographic studio and learned the Mayan language. However, he was still eager to discover more remains from Mayan culture, so he spent most of his time in the forests in the company of a few Maya who helped him clear the way through the jungle and to carry his photographic equipment.

He visited the sites of Uxmal and Chichen Itza where he remained for three months, documenting the ruins as no explorer had done before him. Maler was the first explorer to record many of the ancient Mayan sites. Over the following years, he investigated the sites in the El Petén region of Guatemala and along the course of the Usumacinta River.

This Austrian and naturalized Mexican explorer became disgusted with the practices and behavior of the late 19th century explorers and archaeologists who would remove sculptures and architectural works from their original sites to take them back to European and North American cities. Often noting the damage caused, Maler dedicated himself to writing to the Mexican government about a change in the legal approach to the issue, as well elaborating on the subject more broadly. Today, his views are considered to have been ahead of their time.

Realizing the importance of his investigations, in 1898, Maler started publishing his reports through the Peabody Institute of Harvard University. It resulted in a series of important books being published by the Institute. However, the relationship between it and Maler became strained due to a difference in opinion as to what should be published and what should not.

The author required a detailed report of his work to be issued while the Peabody editors included less of it. Their communication was also made difficult due to Maler’s frequent expeditions into the jungle, during which time he couldn’t be reached, often for months at a time. The Peabody Institute ended their agreement with Maler in 1909. However, it took the Institute until 1912 to finish the publication of Maler’s material. And these books based on his article are still an essential reference in Maya studies.

In 1905, Maler retired from his jungle expeditions to his home in Mérida, Yucatán. In 1910 he traveled back to Europe hoping that institutions there would be willing to publish his reports but his biggest success was in selling his photographs to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

In his later years, Maler was known to have become depressed because of his failure to share his knowledge and became referred to as a misanthrope. Although he made a modest living out of selling his photographs to archaeologists and tourists, his financial situation was also rather unstable due to making some poor investments in the past. He also gave lectures on architecture and Maya art at the Mérida school of fine arts until his death in 1917 at the age of 75.

Many of his accounts were published posthumously, one batch in the 1930s, with more appearing in the 1970s and 1990s.