Most people who see the swastika sign (卍) think of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party from World War II.

The original name for the symbol, however, is fylfot. It was used thousands of years ago as a sacred symbol in pre-Christian religions, by Hindus, Shintoists, Odinists, and Druids. The sign usually represented the sun.

Vikings used the fylfot as a decoration on their Oseberg ship around 800 AD. It also appeared in ancient Greece; a Greek vase from ca. 300 BC displays an image of Athena, the goddess of wisdom, with fylfots decorating her clothing.

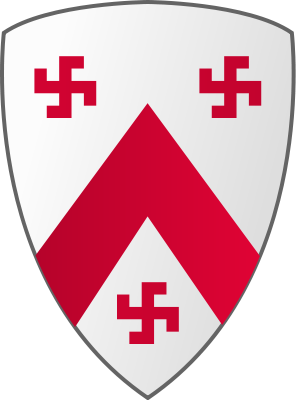

The sign even appears in the Christian faith, as demonstrated by a Welsh engraving on a 12th-century church that shows Christ carrying the sign of the swastika. The symbol was used extensively in jewelry, funerary urns, and war helmets in Great Britain between the fifth and ninth centuries AD.

The “Prose Edda,” an Old Norse piece of poetic literature written around the year 1220, was thought by Snorri Sturluson (a 13th-century Icelandic historian) to have a fylfot on the front cover. Aviators in the early 20th century believed the swastika would bring them good luck, so one was painted on the inside of the nose cone of The Spirit of St. Louis, which was Charles Lindbergh’s plane for his famous transatlantic flight in 1927.

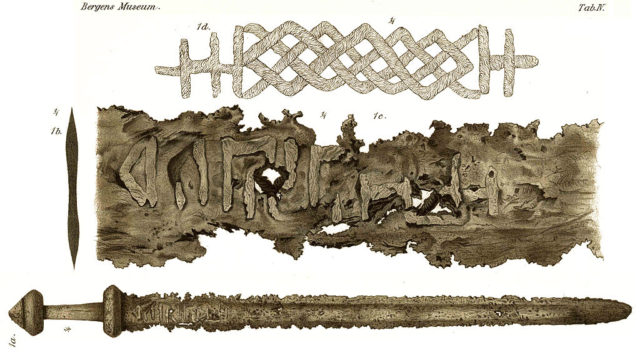

A prime example of the use of the fylfot is the Sæbø, or Thurmuth, sword. This early ninth-century Viking sword was found in Sæbø, Vikøyri, in Norway’s Sogn region in 1825. Now housed at the Bergen Museum in Bergen, Norway, the sword has an engraving that includes a fylfot on its blade.

“De Norske Vikingsverd” (The Norwegian Viking Swords), published in 1919, was written by Jan Petersen and translated for the internet by Kristen Noer at vikingsword.com. This work is considered the best reference for classifying Viking swords.

Peterson divides Viking swords into six types with nine sub-classifications, placing the Sæbø sword in type 2-C – from the earliest Viking age, or the sixth century until about the ninth century. These swords were colossal and heavy; some had blocky features, and some had decorative features. Peterson notes that only one sword weighed less than five pounds.

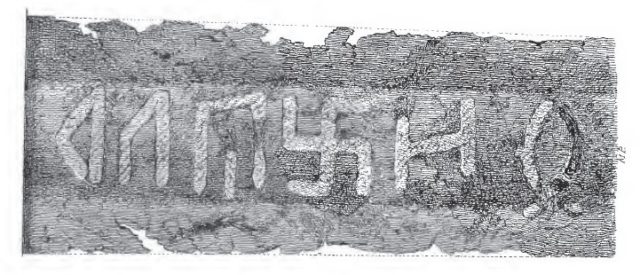

Nineteenth-century British author and archaeologist George Stephens, who moved to Denmark in the late 1840s, described the weapon in his “Handbook of the Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England” in 1867. It included an illustration of the Sæbø sword, with an inscription of five rune-like letters and a swastika symbol in the middle. Stephens translated the inscription from right to left as “oh 卍 muþ,” which demonstrates rebus-writing. This script, like Egyptian hieroglyphs, used symbols rather than an alphabet to tell a story.

The inscription is in an iron inlay along the center of the blade, close to the hilt, and is almost undecipherable. According to Stephens, the blade was once treated with acid, irreparably damaging the inscription. The closest English translation reads “Thor Owns Me,” referring to the Norse pagan god Thor. The swastika traditionally represented Thor’s hammer. In 1876, the International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology at Budapest conducted a discussion regarding the symbol’s meaning; most agreed the swastika represented a blessing or good luck.

Thor was the Norse god of thunder, lightning, and strength, to name a few attributes. He is probably the most well-known of the Germanic gods, as his exploits had been written about in poems and stories as early as the Roman era.

Read another story from us: The massive forest swastika that remained unnoticed until 1992

Thor exists in modern times as well, in the form of a superhero resurrected by Stan Lee and Marvel Comics.