The possibility of communicating with the dead has fascinated and terrified humanity for eons.

Having the spirits of departed loved ones communicate with the living is an age-old practice that is as much believed as it is ridiculed. But in the late 1800s in America, a novelty appeared that promised to answer “with great accuracy” questions about the past, present, or future.

The very earliest recorded instance of using a pointer, or planchette, to communicate with the spirit world comes from ancient China around 1100 AD. During the Song Dynasty, the practice was prevalent and known as “Fuji.” It was carried out under specific guidelines and with supervision, but by the time of the Qing Dynasty the practice had been forbidden. Research has shown that similar types of “automatic writing” were practiced in other ancient cultures, including the Greek, Roman, and Medieval European societies.

The Ouija board of today was born from the rise in spiritualism in America after the Civil War. After the devastation of that war, spirit mediums were in great demand to talk to dead relatives, and they grew more and more common toward the end of the 1800s. The popularity of spirituality, which many saw as almost complementary to their Christian beliefs, was fanned by mediums such as the Fox sisters in New York, who communicated with the spirits by having them rap on the walls to answer questions. The belief that the dead wanted to communicate with the living gained popularity, but it took a very long time to tap out a message on the walls of the parlor, so it was inevitable that an entrepreneur would soon produce something that sped up the process.

That entrepreneur was Charles Kennard, who, with several backers, including an attorney, Elijah Bond, and a surveyor, Colonel Washington Bowie, set up the Kennard Novelty Company in 1886. The express purpose of this business was to produce talking boards to fill the demand. None of these men were spiritualists; they were simply entrepreneurs who wanted to make money off the wave of spiritualism sweeping the country.

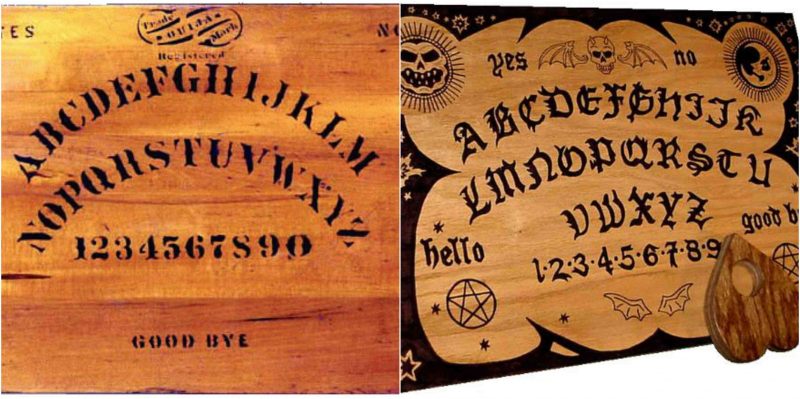

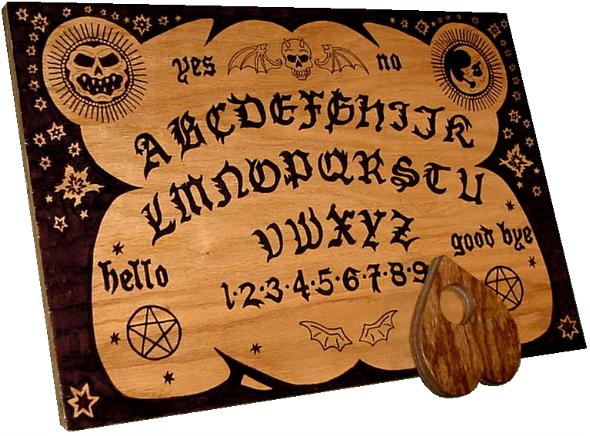

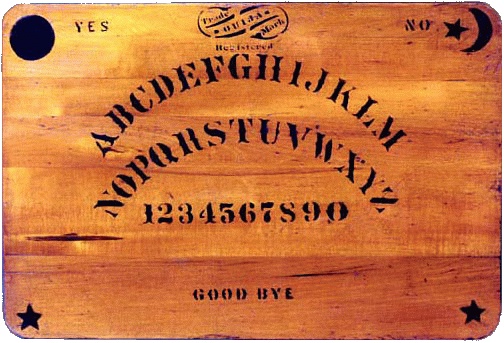

The board contained the letters of the alphabet, numbers from zero to nine, and the words hello, goodbye, yes, and no. The board also came equipped with a teardrop-shaped wooden pointer, the planchette, that was used to point to a particular character or word. Alternately, the planchette had a hole drilled through it which could highlight the particular character or word.

The talking board that the Kennard Novelty Company had produced needed a name, and the name was supplied by Helen Peters, reputedly a spirit medium who was also Elijah Bond’s sister-in-law. According to research done by Brandon Hodge, a historian interested in spiritualism, Peters conducted a séance in which she asked what the name of the new talking board should be. Apparently, the board replied “Ouija.” This word made no sense, so they asked what it meant; the board apparently told them it meant “Good Luck,” so that is what the board was named. Adding to the mystery surrounding this naming of the board, Peters was wearing a locket containing the portrait of a woman, and the word Ouija was written above her head. Taken altogether, this made for a suitably mystical naming.

The team needed to apply for a patent for their new board, and the application papers were duly filed. The patent office insisted that the Kennard Novelty Company prove that the board worked before the patent could be awarded. Elijah Bond was accompanied by Helen Peters when the application was filed, and the Chief Patent Officer insisted that they use the board to tell what his name was–he was certain that neither Bond nor Peters knew what it was. Apparently, the board was set up, and Helen used it to spell out the patent officer’s name; a very disturbed Chief Patent Officer granted the patent on February 10, 1891. Whether the spirits came to the assistance of Bond and Peters or whether Bond, who was a patent attorney, knew the Chief Patent Officer’s name, is not recorded. It’s your choice which scenario you decide to believe!

The patent does not claim to know how the board works; it simply states that it does. The Kennard Company made no effort to describe how the board worked in any of its advertising material; their aim was to make the board appear mysterious and mystical. The less said about the how, and the more said about the supposed results, ensured that the board was viewed as mystical and imbued with spiritual powers.

Sales of the board were excellent, and it proved to be a money-maker for the Kennard Novelty Company. It grew so large they had two factories each in Baltimore, New York City, and Chicago, and one was built in London. By the time 1893 rolled around, Kennard and Bond had left the company, and William Fuld was running the entire operation. Fuld had started as an employee when the company was launched. Fuld died in a most remarkable accident in 1927. He was on the roof of a new factory supervising the erection of a flagpole when the metal support that he was holding onto failed, and he fell from the roof. He grabbed for the windowsill of an open window, but the window slammed shut, and he fell to the pavement, breaking several ribs. His injuries were severe enough that an ambulance took him to the hospital. But on the way, the ambulance lurched over a bump in the road, which caused one of the broken ribs to pierce Fuld’s heart, killing him instantly.

The Ouija board remains a success to this day. It has found a place in popular culture and is seen almost as a rite of passage for many young people. In times of trouble, people will always turn to a mystical or higher power, and so it is today as in the difficult times in the past. The Great Depression, the two World Wars, the Vietnam War, the Cold War–all provided fodder for the use of the Ouija board. In 1967, Parker Brothers bought the rights to the board from the Fuld Company and sold 2 million boards, Smithsonian reported.

Stories of people using the board have appeared in the press since its inception. One of the strangest stories came in 1958, when a court in Connecticut upheld the will of Mrs. Helen Dow Peck. She had left money to two servants, but the bulk of her estate was to go to Mr. John Gale Forbes, a spirit whose name was given to her by a Ouija board. There is no record of how the money was eventually distributed!

Whether you choose to believe that the board is a means of communicating with the dead or, as scientists will tell you, the planchette is moved by involuntary movements of the fingers of the people holding it (known as the ideomotor effect) is irrelevant. The Ouija board will continue to be produced and will continue to fascinate and terrify people for many years to come.