The terrible dangers faced by prostitutes, even the more upscale types, were made all too clear to 19th century America after a woman was killed in a brothel by a regular client.

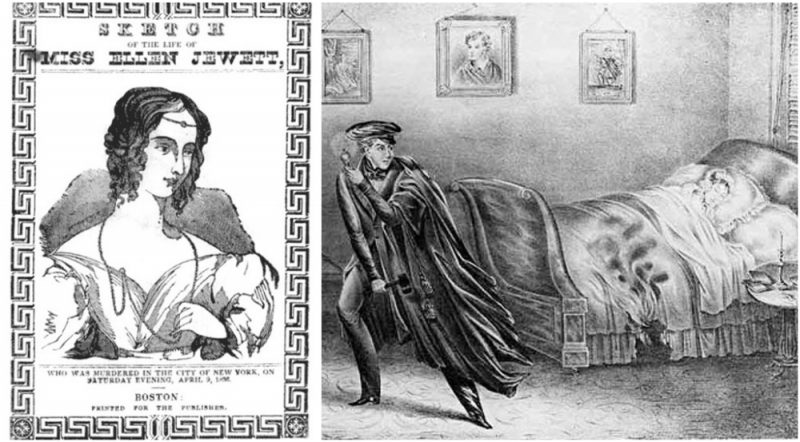

The woman’s name was Helen Jewett. Her murder, along with the following trial and her murderer’s exoneration, drew groundbreaking public attention. It was the first time a sex crime of this sort was covered extensively in the American press.

Born to a working-class family in Temple, Maine, Jewett’s real name was Dorcas Doyen. Although she was known as “Helen Jewett,” Doyen frequently changed names, a common practice at the time. Jewett’s father was an alcoholic, and her mother died when she was young. Employed at the age of only 12 or 13 in the home of Chief Justice Nathan Weston of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court, Jewett spent four years working as a servant girl. As she grew older, she transformed into an assertive young woman, aware of her beauty, and she left her job by the age of 18.

After moving to Portland, Maine, Jewett started working as a prostitute. She eventually moved to Boston, and finally to New York City where she operated under various names, but became well-known by her last one–“Helen Jewett.” The brothel where she worked was an upscale one, known to cater to lawyers, merchants, and politicians.

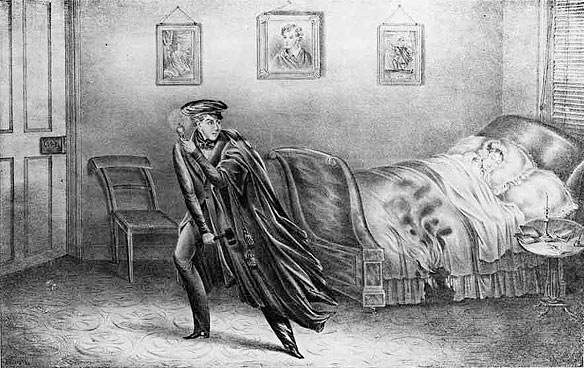

Jewett was murdered in that brothel on April 10, 1836. Her body was found by the matron of the establishment, Rosina Townsend. She reportedly found Jewett at 3 a.m., leading to the assumption that she was murdered sometime after midnight. Her head had been struck three times with a sharp object, believed to be a hatchet. Although there were no signs of struggle, it’s assumed that Jewett didn’t expect the lethal blows, due to the position of her corpse on the bed. As if the murder itself wasn’t enough, her murderer set fire to Jewett’s bed.

After interviewing another woman who lived at the brothel, the police arrested Richard P. Robinson, 19. Allegedly, Robinson, an employee at a dry goods store, was a frequent client of Jewett and they had exchanged letters. He denied killing her without any display of emotion.

On June 2, 1836, Robinson was arrested on the judge’s instructions. At his trial, Robinson was represented by a former district attorney. Because most of the witnesses were prostitutes and not seen as believable, Robinson was found not guilty in less than an hour into his trial. His exoneration excited the media and the public. Some expressed compassion for Jewett, condemning Robinson as a cold-blooded killer, while others supported Robinson, condemning Jewett as someone who deserved her fate.

Full coverage of the sensational murder was provided by the New York Herald, edited by James Gordon Bennett, Sr., the founder of the newspaper. Jewett was sometimes called “the girl in green,” as that was her favorite color. Many readers stopped by the newspaper’s offices, publicly expressing their opinion on the murder. According to them, Robinson was well off enough to buy his freedom, and this theory was widely accepted over the years.

After the trial, Robinson’s personal letters were released to the public, revealing his cruel and deviant sexual behavior. The letters turned the public against Robinson, convincing them that he was the murderer, forcing him to move out of town.

He eventually moved to Texas, where he seems to have become a respected citizen.As for Helen Jewett’s murder, the case was never reopened.