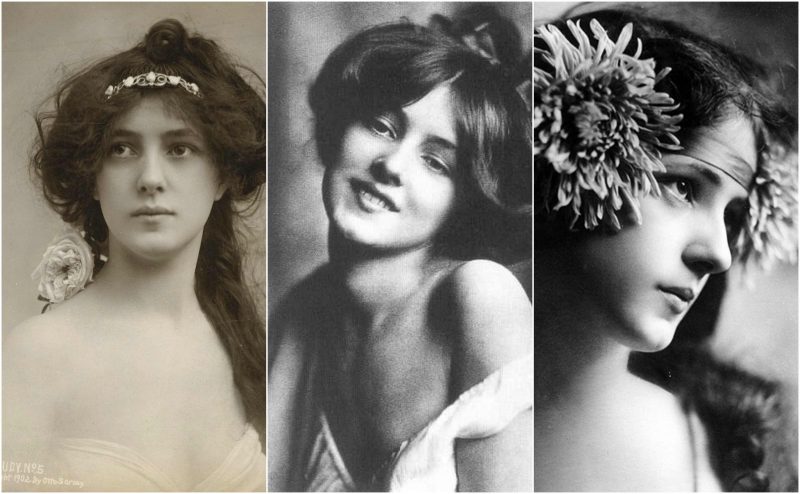

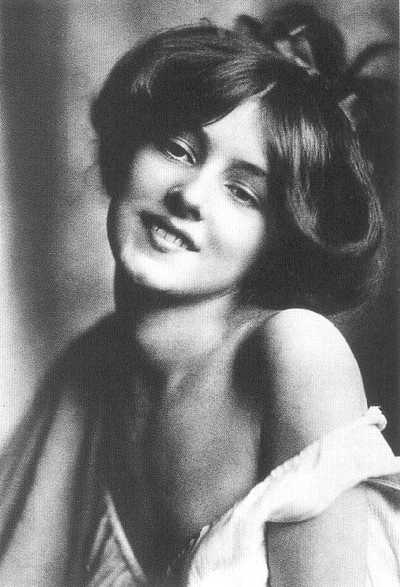

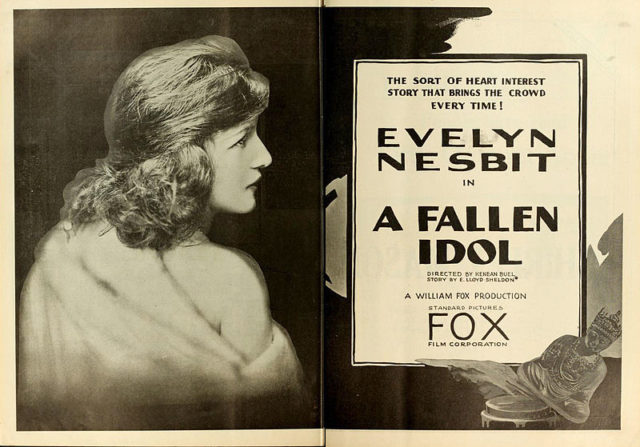

Evelyn Nesbit, whose stunning beauty enchanted the New York community of artists as well as the budding marketing world during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was one of Charles Dana Gibson’s idealized “Gibson Girls.” She was desired by artists who wanted to paint and photograph her, by companies that wanted to use her image to advertise their products, and by men who wished to possess her, and yet ultimately her beauty proved to be more of a curse for Evelyn than anything else.

She was a top-rated artists’ model, actress, and chorus girl since the age of 14. She married multi-millionaire Harry Kendall Thaw when she was 20.

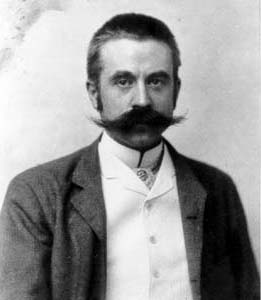

But Nesbit’s fame took a very dark turn after the scandalous murder of architect and New York socialite Stanford White by Evelyn’s crazed husband, Thaw. The shooting happened on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden Theater in June 1906, and led to what the press called “the Trial of the Century,” the first time that phrase was used. The reason for the millionaire taking White’s life was his belief that White had raped Nesbit when she was 14.

Evelyn was born in 1884, in a town near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. After the death of her father when she was only 11, her mother, a housewife who had never done any labor, was forced to support Evelyn and her younger brother. Struggling to find a job and having a hard time separating her expectations from the reality of the job market, Mrs. Nesbit was never successful in maintaining an income and feeding her children. Quite often, the family of three lived in the houses of relatives, relying on their financial support. She left for Philadelphia expecting to find work as a seamstress, leaving her children at her relatives’ house in Pittsburgh.

Instead, Mrs. Nesbit became employed as a sales clerk at the fabric counter of Wanamaker’s department store, and after a few months, she took Evelyn and her brother Howard to join her. They both started working with their mother, and regardless of their age (Evelyn was 14, her brother 12 at the time), they worked 12 hours every day, for six days a week.

Around this time, Evelyn had an encounter with an artist who was stunned by the teenager’s beauty and evocative charm. This meeting led to Nesbit posing for a painting for which she earned one dollar (equivalent to approximately $27.50 in 2017). Realizing that there was another, much easier and more enjoyable way to make money, Evelyn decided to pose for artists. Even though her mother was never supportive of it and the girl always had to convince and beg, money won.

Evelyn’s mother’s next destination was New York City, a place suitable for Evelyn’s dreams. Instead of the easy job that she was hoping for, Mrs. Nesbit faced even stiffer competition. Poverty and desperation led to the decision that Evelyn would become the financial supporter of the three, and hence the girl was sent to model for many artists. The first contact was James Carroll Beckwith, who willingly made a portrait of Evelyn, and it was after this that the world of artists opened its doors to her. She was the most desired model of her time.

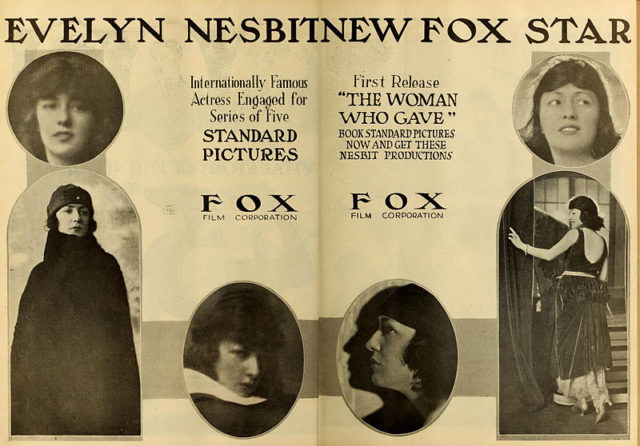

She posed for Frederick S. Church, Carle J. Blenner, Herbert Morgan, Carle J. Blenner, Rudolf Eickemeyer, Otto Sarony, and many other New York artists. She became the most popular face on the covers of women’s magazines of the period, including Cosmopolitan, Vanity Fair, The Delineator, Harper’s Bazaar, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Women’s Home Companion. Inside the magazines, the teenage model was advertising face creams, toothpaste, and a range of other kinds of consumer goods. Evelyn’s face was printed on tobacco cards, postcards, beer trays, pocket mirrors, chromolithographs, you name it. Posing for calendars for Coca-Cola, Swift, Prudential Life Insurance, and other corporations, she became the very first pin-up girl.

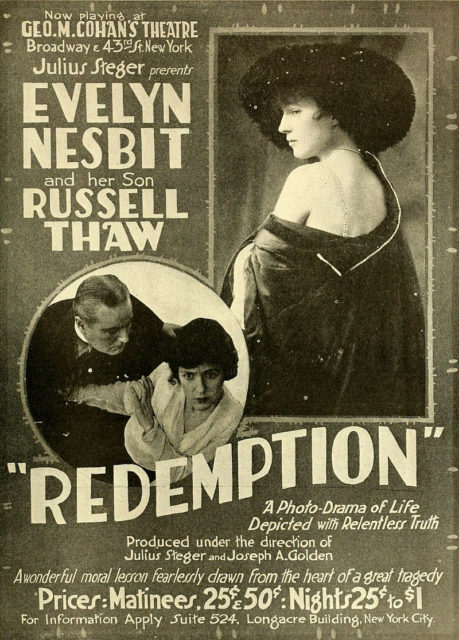

She was the most sought after model, and her schedule was full, but soon, the teenager became bored with just standing for long hours, posing in front of artists, and so persuaded her mother to let her start an acting career. After an interview with John C. Fisher, company manager of the wildly popular play Florodora, which was performed at the Casino Theatre on Broadway, Evelyn got a part as a member of the show’s chorus line. Soon after, she won a part in The Wild Rose, again on Broadway. She was offered a contract for a year as a featured player in the role of the Roma girl “Vashti.” In the press, Evelyn was always praised for her beauty and her acting skills were rarely in the focus.

It was at this time that Stanford White arranged to meet Evelyn through friends. White soon befriended the Nesbits, providing them with a much bigger apartment, and also helping Howard get in the military academy. He helped the Nesbits financially, and in return, he was always around Evelyn. Even though he presented himself as a parent figure to her, it turned out that his intentions were not parental at all.

One time, when White was assured that Mrs. Nesbit was traveling to Pittsburgh, he invited Evelyn for dinner at his apartment. According to Evelyn’s later accounts of that evening, they were drinking champagne until she started feeling dizzy, and the last memory she had was changing into a yellow satin kimono. The next morning she woke up next to White, half-naked. She never mentioned this to anyone at the time, and White continued his fake role of protective parent.

When she was 17, Evelyn met the future movie star, John Barrymore, known as “Jack,” who at the time was trying to avoid his family path in the acting world and pursue a career as an illustrator and cartoonist. Unfortunately, it didn’t earn him a lot of money, at least not enough to be considered as an opportunity for Evelyn. So even though she was fond of him and was dating him for some time, their relationship displeased Mrs. Nesbit and White. White actually made a plan of separating the couple by arranging for Evelyn to enroll at a boarding school in New Jersey, and even though Barrymore proposed to Evelyn in front of her mother and White, she refused him.

There were many men who vied for Evelyn’s attention, and she wanted to be sure that she would make a choice that would give her firm financial security. At the same time, she was involved with the polo player James Montgomery Waterbury, also known as “Monte,” the young magazine publisher Robert J. Collier, and the son of a Pittsburgh coal and railroad baron, Harry Kendall Thaw. In the end, Thaw’s money won Evelyn’s attention and soon after, they, along with Mrs. Nesbit, were on a trip to Europe. Despite all that Thaw’s money could buy, he was an unstable, strange person and instead of the glamourous trip to the European cities they had expected, Thaw made a fast-paced itinery to wear out Mrs. Nesbit so that she would leave her daughter alone with him. The subsequent growing tensions between mother and daughter finally did result in Mrs. Nesbit staying in London and returning to the U.S. while the other two continued on to Paris.

While in Paris, Thaw asked Evelyn to marry him, but she refused. Aware of Thaw’s obsession with female chastity, she couldn’t agree to a marriage with a clear conscience, so she revealed her secret for the first time. She told Thaw what White had done to her, and he became completely enraged. Then, horrifyingly, he took Evelyn to a castle in Austria where she became his prisoner. For two weeks, he beat her with a whip and sexually assaulted her. He apologized afterward, saying that he didn’t know what had gotten into him.

And yet, financial security meant enough for Evelyn to forgive him and to accept his marriage proposal, although it took four years of him persuading her to do so. Thaw’s mother agreed to the marriage only under the condition of Evelyn giving up her modeling and acting career. She did so and went to live in the family’s mansion with her new husband and his religious mother. Mama Thaw was the head of the house, setting all the norms of behavior. In the meantime, Mrs. Nesbit found a husband and had become completely estranged from her daughter.

On the 25th of June, Thaw and Nesbit were spending a night in New York before setting off to Europe for their holiday. Thaw purchased tickets for Mam’zelle Champagne, a new show written by Edgar Allan Woolf that had its premiere that evening on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden Theater. At night, as they were meeting some friends, they encountered White but calmly continued to the roof. Around 11 o’clock that evening, as the show was coming to an end, Thaw took a pistol from his coat and shot White three times in the head and in the back, killing him.

The next day, all the media covered the event, revealing Evelyn’s secret. According to some reports, Thaw was heard to scream “You ruined my wife” and to others “You ruined my life.” Evelyn was not spared the social and media judgment. Instead of defending her, people were attacking her. Thaw was imprisoned, but Mama Thaw spent millions of dollars on doctors and attorneys who would play the card of “subtle insanity.” She wanted not only for her son to avoid prison, but also to make a victim of him while not marking him with insanity. Money bought him a place in a hospital where he was accommodated in a luxury apartment.

Evelyn gave birth to a son, Russell William Thaw, in 1910, in Berlin. Even though she always maintained that the child was Thaw’s son, conceived during a conjugal visit to Thaw, he denied paternity. They divorced in 1915 and Evelyn married the dancer Jack Clifford in 1916, with whom she worked in a stage act. Their marriage sadly wasn’t a successful one. It seemed that the public didn’t permit her to start a new life, calling her “the lethal beauty,” always associating her with the “playboy killer.” Feeling that his own identity was being subsumed into that of Evelyn’s, Jack left his wife in 1918, and she finally divorced him in 1933.

In 1926, Nesbit swallowed disinfectant in a suicide attempt, after losing her job as a dancer at the Moulin Rouge Cafe. Until that time, Thaw still had a detective following his ex-wife and kept paying her money (10 dollars a day), for, as he stated, it was “a token of pleasant memories of the past when we were happy.” He visited her in the hospital in Chicago, but contrary to rumors of reconciliation, the couple never got back together.

In 1914, Evelyn published her first memoir, The Story of My Life and in 1934 she published a second, Prodigal Days.

She worked as technical advisor for the 1955 movie The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing, which proved to be a highly fictionalized account of events in Nesbit’s life, then lived quietly in New Jersey for several years. She died in a nursing home in Santa Monica, California, in 1967, at the age of 82.