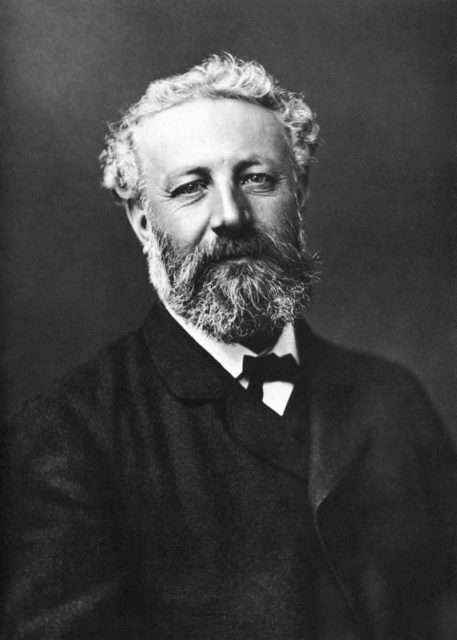

In 1873, Jules Verne published Around the World in Eighty Days, a novel that immediately became an international success and still remains one of the most influential adventure novels of all time. The plot follows a London gentleman named Phileas Fogg and his French valet, Passepartout, as they attempt to circumnavigate the world in 80 days. Since the two men succeed in their fictional effort, the novel inspired many enthusiasts across the world to try and break Phileas Fogg’s record.

In 1888, a reporter at New York World magazine named Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman, known by her pseudonym Nellie Bly, suggested to her editor that she should try and break the fictional record set by Phileas Fogg.

Bly was not only an avid traveler but also a famous and acclaimed journalist: several years earlier, she infiltrated an insane asylum by pretending she was mentally disturbed and experienced the dirty and inhumane conditions of the institution. Her report, published as a book called Ten Days in a Mad-House, brought her lifelong acclaim and motivated the American authorities to increase the budget of the Department of Public Charities and Corrections.

Bly’s editor was fascinated by the idea of her attempting to break the record, so a year later, on Nov. 14, 1889, she boarded the Augusta Victoria, a steamer of the Hamburg America Line, and began her journey. Her voyage was widely publicized and received a lot of attention from the public: A huge crowd gathered and cheered as her ship departed from New York.

At the same time, Cosmopolitan magazine arranged for their own reporter, Elizabeth Bisland, to undertake the same journey. She also set out from New York but went in the opposite direction. So, Bly’s idea of turning “Around the World in 80 Days” into reality turned into a race between two American women.

For most of her journey, Nellie Bly traveled alone. She was extremely well-organized and carried only the essentials that she deemed absolutely necessary: her favorite dress, a well-insulated overcoat, several changes of underwear, and a handbag containing her toiletry paraphernalia. The magazine supplied her with 200 British pounds in banknotes and gold; she carried all of the money in a small cotton bag tied around her neck.

Bly visited most of the places that Fogg visited during his journey, including the Suez Canal, Colombo in Sri Lanka, China, Hong Kong, and Japan. When she was passing through France, she actually met Jules Verne and he was amazed by her pioneering spirit. She even managed to visit a leper colony in China and buy a pet monkey in Singapore.

Bly reported her progress through telegraphs, which she sent from many places across the world. When she arrived in San Francisco on Jan. 21, 1890, she was two days behind schedule. The delay was caused by harsh weather conditions which slowed down RMS Oceanic, the ship that carried her over the Pacific Ocean.

Upon her arrival, the editorial staff of New York World were worried that she might not be able to finish her journey in time, or, even worse, that she might lose to Elisabeth Bisland, who was approaching the United States from the other side. In order to secure the outcome of her journey, the then-owner chartered a private train that brought her to New Orleans. Bly arrived in New York on Jan. 25, 1890, just over 72 days after her departure and four days before Elizabeth Bisland.

Bly’s journey was a world record. It was broken only several months after she returned to New York, though, by George Francis Train, who managed to circumnavigate the globe in 67 days.

This was Train’s second trip around the world: his first trip, in 1870, partially inspired Verne to write Around the World in 80 Days. During his second trip, he broke his own record.