The first message ever transmitted over telegraph wire was on May 24, 1844, sent across an experimental line from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. The message was “What hath God wrought?”

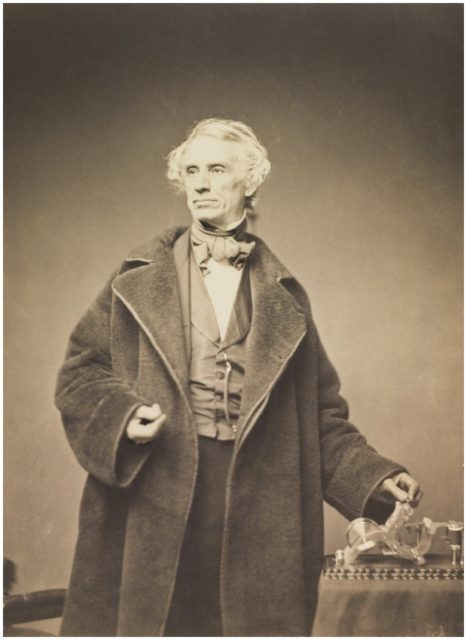

Samuel Finley Breese Morse, the developer, created this technology out of his grief for his deceased wife, after he was unable to attend his wife’s funeral due to slow mail delivery.

Heartbroken, yet determined to revolutionize long-distance communication, Morse dug deep and explored every means available to develop the technology that would allow fast transmission of signs, signals, or messages for people willing to exchange information but separated by distance. He invented Morse code in 1837 and in 1844 patented his inventive single wire telegraph, changing the course of history.

Nowadays, most recognize Morse as the inventor of the telegraph and the system of long and short signals he developed as a mean for long distance communication.

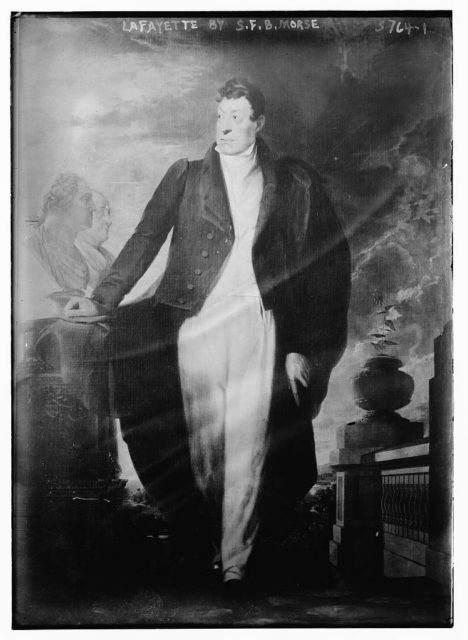

But before he became known for the code that bears his name, Samuel Morse was a refined and established painter who earned his living by making elaborate and critically acclaimed portraits of famous figures, including the 5th president of the United States, James Monroe, and Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, the French nobleman who was a hero of the American Revolution.

Born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, as the first child of Pastor Jedidiah Morse, Samuel attended the distinguished Phillips Academy in Andover, after which he went to Yale College to learn more about religious philosophy, mathematics, and science.

Morse graduated as an outstanding student from Yale in 1810, showing excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, for which he was bestowed with the highest honors by the nation’s most prestigious honor society, Phi Beta Kappa. During all this time, he supported himself by painting.

In his early years, his works mirrored the Calvinist beliefs of his father and his religious living environment. After his graduation, Morse moved to London, where he was admitted into the Royal Academy of Arts. Here he mastered fine arts and perfected his style and technique. In his new environment, deeply excited by the art of the Renaissance, especially the works of Michelangelo and Raphael, Morse found himself attracted to human anatomy and figure drawing. After a while, he produced one of his best works, the Dying Hercules, pictured above.

Many considered it represented Morse’s political views and saw it as a rebellious statement against the American Federalists and their coalition with Britain during the War of 1812, a conflict fought between the United States and the United Kingdom. They saw the muscles as the strength of the fresh and spirited United States against the British and their supporters who opted for a strong centralized government. His painting Judgment of Jupiter is critiqued as confirming the sympathies held towards Anti-Federalism, whilst still embracing the strong spiritual influence of his father.

In 1815, Morse decided to move back to the United States to continue working full time as a painter. The following decade is viewed as his most progressive one, during which he grew significantly as an artist and expressionist, focusing on America’s cultural life as his prime inspiration. It was in these years that he perfected his realistic portrait drawing, having painted President John Adams, Dartmouth College President Francis Brown and Judge Woodward in 1817, among many others.

Life was good for Morse, and his work was much requested among political circles. In 1820, he was commissioned to paint President James Monroe, the last president among the Founding Fathers of the United States.

After that, Morse was well established in Democratic circles and in the early 1820’s was awarded the greatest of honors, to paint a portrait of Marquis de Lafayette, the supporter of the American Revolution.

He wanted to paint a grand portrait of a great man, one who served bravely a free and independent America. For this reason, Morse placed Lafayette against a brilliant sunset, positioned to the right of three pedestals: one of Benjamin Franklin, another one of George Washington, and the third, reserved for Lafayette himself. They became close friends in the process, sharing similar political views.

In 1825, while he was still painting the portrait, a messenger arrived with a letter from his father, informing him his wife had fallen seriously ill after the birth of their third child. He left immediately, leaving the portrait unfinished. But this was to no avail, for when he arrived back home, his wife was already dead and buried.

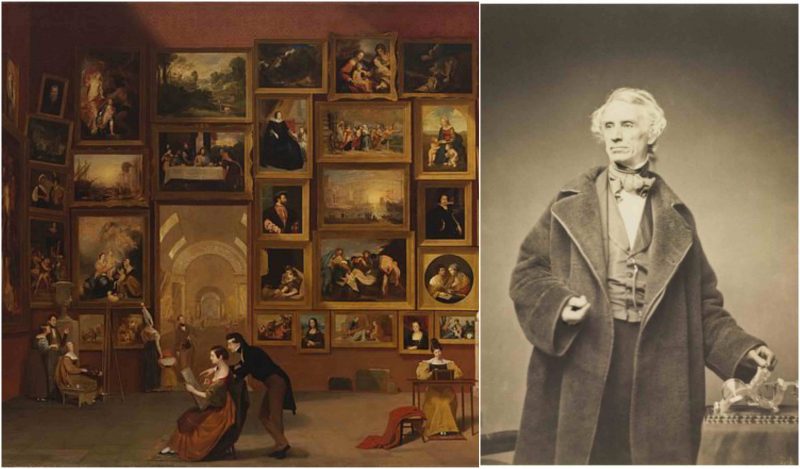

Devastated, he started roaming through Europe, hoping to find peace of mind. While still in France, he took on a project as a challenge and painted one of his most famous paintings, The Gallery of the Louvre, in which he drew 38 miniature copies of some of Louvre’s most famous paintings. This picture was left unfinished, abandoned by Morse in 1832 as he focused on developing his single wire telegraph.

He died in New York on April 2, 1872. Some of his paintings are on display at the Locust Grove estate in Poughkeepsie, New York. The estate includes a home designed as an Italian style mansion by architect Alexander Jackson Davis as requested by Morse. It was completed in 1851.

Related story from us:The code of Margaret Hamilton that got humans to the moon

The estate is open to the public, and interested parties can often take part in or arrange themselves a tour so they can walk through the museum and nature reserve and the gallery showing Morse’s artworks, incorporated in the estate.