Roger Fenton, the man who would make history as the photographer of the Crimean War, was raised in great comfort in England. He was born in Rochdale, Lancashire, on March 28, 1819; his father was a Member of Parliament and a banker, and his grandfather was a cotton industrialist and also a banker. He was educated at the University of Oxford, graduating in 1840.

He was interested in art rather than banking, and in 1842 went to Paris to study art. Fenton returned to England and continued his studies with historical painter Charles Lucy. In 1849, and for the next two years, he exhibited artwork at the presentations of the Royal Academy.

In 1851, Fenton visited the Great Exhibition, where he saw a photography display. He was so fascinated that he traveled to Paris to study photography with Gustave Le Gray. He afterward made his way to Russia and took pictures of landscapes and buildings; he continued his work in Britain as well. A year later, he was exhibiting his own photographs, and in 1853, he established the Photographic Society.

In autumn of 1854, Prince Albert and Henry Pelham Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, Fifth Duke of Newcastle, Secretary of State for War, asked Fenton to go to Crimea to document the conflict. War had broken out in October 1853 between Russia and Britain, France, Turkey, and Sardinia over Russia’s expansion into what is now Romania. Originally, the conflict had started between Turkey and Russia, but fear of Russian expansion into British-ruled India compelled Great Britain to become involved, with help from France. The main focus of fighting was on the Crimean Peninsula and the Black Sea, but particularly the Russian naval base at Sevastopol, the capture of which would hinder Russia’s naval power in the Black Sea.

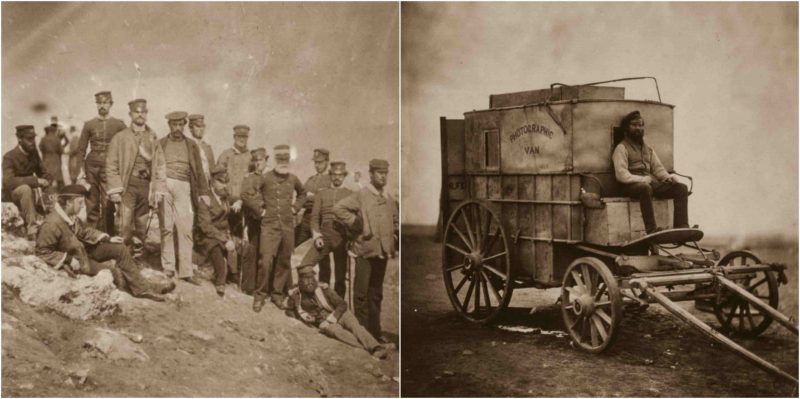

Fenton agreed to go to the scenes of battle and boarded the HMS Hecla along with his assistant Marcus Sparling, a servant called William, and a wagon of equipment. He spent four months taking photographs there.

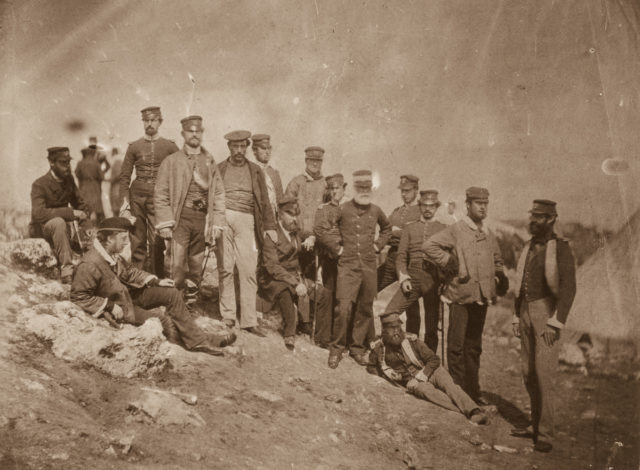

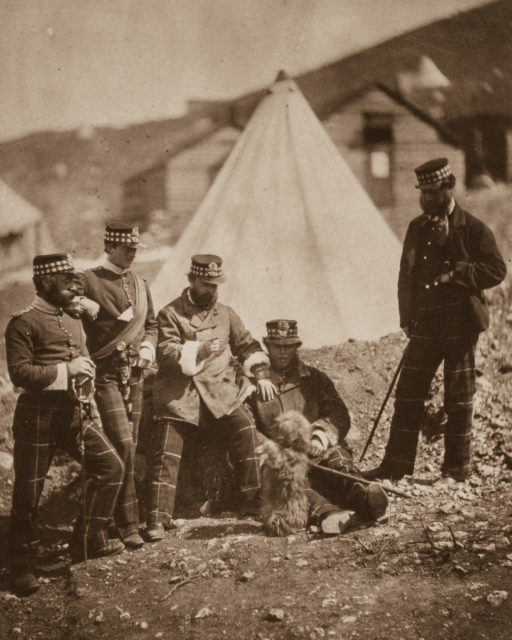

Early photographers had to deal with long exposure times—often as long as three or four minutes—which is why most subjects didn’t smile for pictures. Because of this disadvantage, Fenton was limited as to what he could photograph. He could not take action shots, as the subject had to remain still for the duration of the exposure, and Fenton did not believe in taking pictures of dead bodies. He therefore concentrated on posed shots and on landscapes. His work is admired today for his keen artistic eye, and how he managed to convey the reality of war even though he did not photograph men in battles.

One particular photo was taken in an area close to where the Charge of the Light Brigade occurred. This battle was made famous by Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem of the same name.

During his assignment, Fenton broke several ribs in a fall and contracted cholera, but he was able to produce over 350 large format negatives. When he returned, 312 of his prints were displayed in London and traveled throughout numerous towns in the British Isles. Fenton also presented them to his patrons, Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, and to Emperor Napoleon III in Paris.

In 2007, Academy Award-winning documentary director Errol Morris went to Sevastopol to find the area Fenton had photographed and discovered the small valley the soldiers called the Valley of Death. Of the two pictures taken of this area, one included cannonballs on the road and the other did not. Morris found evidence that the photo without the cannonballs was taken first—he believes Fenton intentionally placed them there for a better picture. It is also possible that soldiers were gathering up cannonballs for reuse and they rolled the balls over the hill to retrieve them later. Nigel Spivey of Cambridge University recognized the images as Woronzoff Road, the location accepted by tour guides.

Fenton did not have much luck selling his Crimean War photos, but he continued to take photographs until 1863, when he became a lawyer in England until his death in 1869.

His photos of the Crimean War are now considered to be the first pictorial documentation of war. A collection of 263 of his war photos were sold to the Library of Congress in 1944 by his grandniece Frances M. Fenton and can be viewed at the Library of Congress.