What better way to spend the 4th than with a hot dog eating contest? Every Fourth of July, the corner of Stillwell and Surf avenues in Brooklyn, New York, is transformed into a media circus, with ESPN broadcasting live an event that for at least an hour puts baseball, America’s favorite summer sport, deep in the shade.

Tens of thousands of people crowd close, breathing in the odor of fried food mixed with salt air, stepping over thick television cables, hearing the screams of seagulls overhead, to witness it: Nathan’s Famous International Hot Dog Eating Contest. Boosted by the popularity of competitive eating, the 4th of July contest is “Major League Eating’s Super Bowl, so to speak,” says sportswriter Mark J. Burns in a Forbes column.

It’s a Super Bowl with stars, no less. Joey Chestnut, 35, the defending champion, won the annual contest for the 11th time last year by downing 74 hot dogs in 10 minutes, which was a record. He is hoping to break that mark on July 4th and two days before switched to a diet of lettuce and water in order to make sure he’s hungry when it’s all on the line. Chestnut gained about 24 pounds during the 10-minute contest in 2018. A former construction manager, Chestnut is believed to earn more than $200,000 a year on the competitive eating circuit.

One wonders what the man who started it all—Nathan Handwerker—would make of this feat today. In 1916, he launched what became a hot dog empire with a small stand on the same corner.

A near-illiterate shoemaker’s son accustomed to 18-hour workdays, at 19 he had left Poland and a family that hovered on the brink of starvation to follow his dream. “We were seven brothers and six sisters and we didn’t have a lot to eat,” says Handwerker in the excellent 2015 documentary Famous Nathan.

That Nathan Handwerker should end up a beloved fixture of Coney Island is perhaps not so surprising, for this stretch of beach in southwest Brooklyn drew the most audacious of all dreamers for decades.

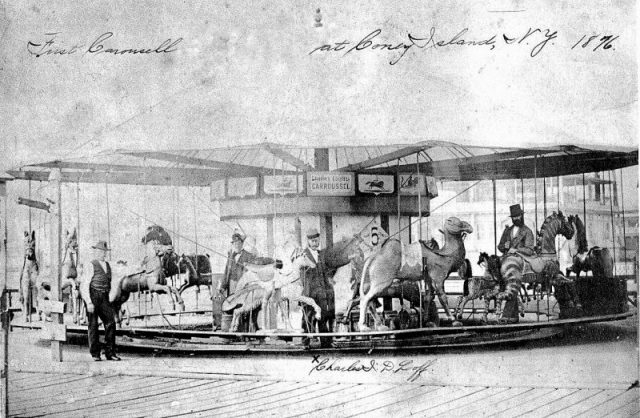

In the 1870s, the part of Coney Island that became a world-famous amusement park was nothing more than the overlooked neighbor of Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach, where large hotels drew well-off families for a summer of ocean breezes and genteel entertainment.

An Irish-born businessman, John McKane, saw an opportunity and wrested control of the real estate of “West Brighton Beach.” A 300-foot-high observation tower was built, billed as the tallest in the United States. Rollercoasters, brand-new inventions, joined the tower, as did a seven-story-high hotel in the shape of an elephant.

The even larger, more fantastical attractions that rose in Coney Island were Steeplechase Park, Luna Park, and Dreamland. Taking advantage of Thomas Edison’s invention, the 250,000-plus electric lights of Luna Park, created by Frederic Thompson and Elmer Dundy in 1903, could be seen 20 miles out from shore.

Besides the Trip to the Moon roller coaster, Luna Park boasted a simulated submarine ride, a cyclone, a ride in Venice’s canals, a trip the north pole, elephant rides, and, incredibly, infant incubators in a room where real doctors held babies for the spectators to see.

At the turn of the century, as public transportation made it possible to reach Coney Island from most parts of the city in an hour, hundreds of thousands of working-class New Yorkers thronged to the attractions on the ocean.

Not everyone was a fan. “Sodom by the sea,” thundered those who feared the sexy exuberance of Coney Island. But as McKane himself once barked to the newspapers, “This ain’t Sunday School.”

Advocates of Coney Island rejoiced in its mix of classes, genders, races, and religions, all come to enjoy themselves. “Coney Island astonished, delighted and appalled the nation, and it took it from the Victorian age to the modern world,” according to the documentary American Experience: Coney Island.

Related Video:

The burning down of Dreamland in 1910 may have ushered in the period of gradual decline that ended in the 1980s of shuttered rides, freak shows, and a skyrocketing crime rate. Coney Island has rebounded today, with a family amusement park and crowded beaches, and down a stretch, a cluster of Russian restaurants with names like Tatiana’s, where a bottle of Vodka rests firmly on many a table.

But between the burning of Dreamland and the present reboot is the life of Nathan Handwerker. He started work in Poland at age 11.

Nathan slept on the floor of a bakery, getting up at midnight to prepare the dough and help bake. When dawn came, he started his deliveries.

After slipping out of Walicia with some difficulty, for the gendarmes sought to prevent men of fighting age from leaving in 1912, Handwerker made his way to Holland and bought himself a fare to New York City. He would find his fate in the hot dog business.

The frankfurter was eaten as least as long ago as the 13th century in Germany. In the late 1860s, on the Brooklyn Beach, Charles Feltman, born in Germany, began selling sausages in long rolls from a pushcart wagon, calling it, at first, the “Coney Island Red Hot.”

Coney Island likes to claim the honor of coining the word hotdog, but there are of course rival claimants. Working in a restaurant where hot dogs sold for a dime, Handwerker had the idea of selling beef hot dogs for a nickel instead and put up a stand. With his wife, Ida, by his side, Handwerker built the business, year by year, adding employees.

Legend has it that in early days, his friend Jimmy Durante, a singing waiter in Coney Island, loaned him some money to grow the business, as did Eddie Cantor.

In the restaurant’s heyday in the 1950s, it sold $3 million worth of hot dogs a year. Famous fans of Nathan’s included Jacqueline Onassis, Walter Matthau, Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand, and Al Capone whenever he hit town.

As for the hotdog eating competition, the story goes that in the first year that Nathan’s opened for business, four immigrants staged a hot dog eating contest there on the 4th of July to prove who was the most patriotic. Soon the contest was an annual event, with local celebrity judges who included Mae West’s father.

CC BY 2.0

In the 1970s the contest became firmly established, under the eye of local promoter Mortimer “Morty” Matz. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Japanese contestants dominated, in particular, Takeru Kobayashi, who stopped showing up in 2009 because he didn’t want to sign an exclusive contract with “Major League Eating,” which has taken charge of the event.

As for Nathan Handwerker, at the instigation of his son Murray, he opened a second branch in Oceanside and then in Yonkers. In 1965 the company went public but seems to have overreached with franchises and a posh corporate headquarters, and the family sold to a group of investors in 1987.

As of last year, there were Nathan’s restaurants in all 50 states and 17 foreign countries. The packaged brands of food are sold everywhere.

A man who said he never wanted to retire, Nathan Handwerker gave in to his family and did retire to Florida, and died there of a heart attack in 1974.

Related Article: America’s Most Famous Hot Dog Stand Used a Rotting Whale to Advertise

He is still a legend in Coney Island, where former employees gathered to talk about the good old days. “Nathan was New York,” declared one of his former counterman.

Nancy Bilyeau, a former staff editor at Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, and InStyle, has written a trilogy of historical thrillers for Touchstone Books. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.