In 1989 Oliver Stone released his Ron Kovic biopic Born on the Fourth of July, based on the best-selling autobiography of the same name. Tom Cruise portrayed a Vietnam War veteran who becomes an anti-war activist after feeling betrayed by the country he bravely fought for in a war that left him paralyzed.

The date has always held great importance in America, no matter the stance.

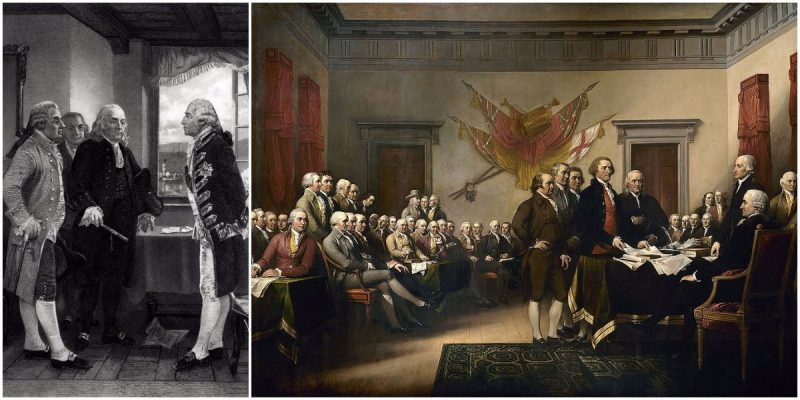

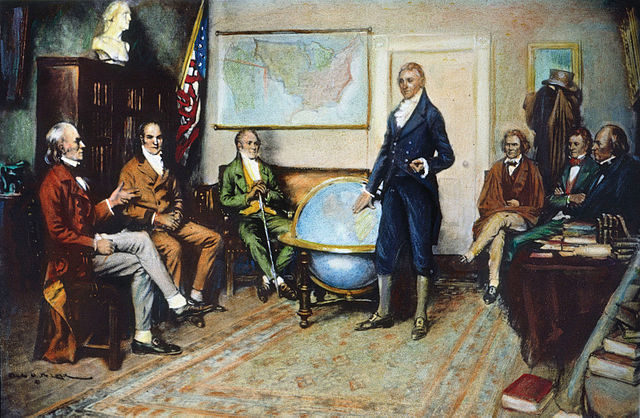

Thirteen representatives of the colonies fighting in the war met in June 1776 to appoint a committee that would draft an official declaration, and on July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress unanimously voted for independence.

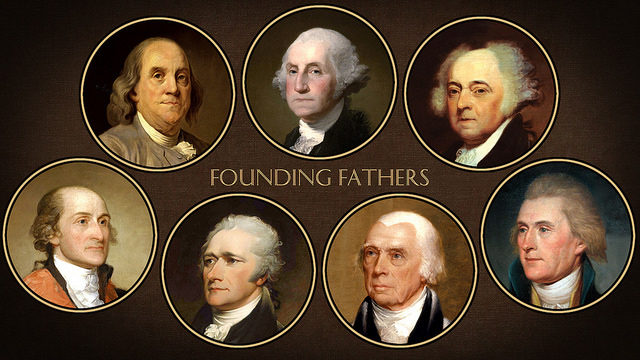

Two days later, the delegates adopted the Declaration of Independence, drafted and written by a team of five men recognized as the key Founding Fathers of the United States. Two of them, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, came to be the second and third President of the United States.

On July 4, 1826, at the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, just a few hours apart, they both died. Five years later, James Monroe, the 5th president and the last president among the Founding Fathers, passed away on the same day.

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826)

Born on October 30, 1735, John Adams was a Harvard graduate, a lawyer, a diplomat, a statesman, an American patriot, and of course, the second President of the United States, serving from March 4, 1797, until March 4, 1801. He was a leader of the movement that resulted in American independence.

He drafted the Massachusetts Constitution, which is the oldest written constitution in the world to still remain in effect. It was approved by the state voters in 1780 and is utilized as such even today. Adams believed July 2nd, the day when the agreement was reached, was actually the date of independence, so he objected and did not accept invitations to celebrate events held on the 4th of July. Despite all of his protests, in 1781 Massachusetts became the first state to make July 4th an official state holiday.

On July 4, 1826, at the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of the Independence, Adams died somewhere around 6.20 P.M. In his last words he paid tribute to his longtime friend and political rival, saying “Thomas Jefferson survives,” not knowing Jefferson passed away earlier that morning.

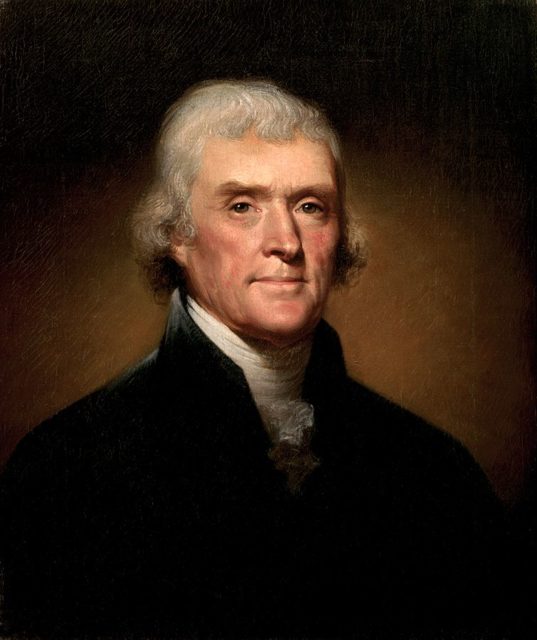

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826)

Jefferson, born in Virginia on April 13, 1743, is recognized as a true Renaissance man. Apart from speaking six languages–English, French, Greek, Italian, Latin, and Spanish–Jefferson was a well read economist, philosopher, and theologist. With his vast knowledge in many fields, he played important roles in the early history of the rising country.

After the adoption of the Declaration of the Independence, Thomas Jefferson served as Minister to France and as Secretary of State, later becoming the third President of the United States (March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1809), after having previously served as a Vice President to John Adams. He is known for his passion for the written word, with more than 19,000 letters in his lifetime, in addition to all the scientific works he left behind.

In his private life, he was a grandfather to 12, all the children living under his roof at one point in time in his Monticello estate in Virginia. If he lived today, he’d be considered a science nerd who deeply cherished technology and innovation. One of his favorite devices was made to support his first love, books. It was a rotating bookstand that could hold five of the many books he owned at the same time. And he owned a lot. In 1814, after British troops attacked the original Library of Congress and burned all the books, Jefferson, now former a former resident, donated his personal library as a replacement. In 1815, the Library of Congress was fully restocked—with his 6,487 books.

On July 3, Jefferson, struck by fever and confined to his bed due to deteriorating health, declined an invitation to attend the anniversary celebration of the Declaration in Washington and died the next day at noon. At the time, the president of the United States was Adams’ son, John Quincy, who called this strange coincidence, of Jefferson and his father passing on the same day and at 50th anniversary of the nation, “visible and palpable remarks of Divine Favor.”

His gravestone reads: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, Author of the Declaration of Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom and Father of the University of Virginia.”

James Monroe (April 28, 1758 – July 4, 1831)

Born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States and the last of the Virginian dynasty, is perhaps the least credited among the founding fathers. Despite his 50 years of loyal servitude given to his country, Monroe more often than not ends up overlooked when credit is being given to the people who laid the foundation of “The Land of the Free.”

Monroe began his service on the battlefield during the Revolutionary War, having previously dropped his studies at the College of William & Mary in order to enlist in the 3rd Virginia Regiment, where he served under General George Washington. During this time he fought major battles in the Northeast that left him with shrapnel in his shoulder for the rest of his life–he was wounded at the Battle of Trenton.

Monroe after his service in the war held more elected public office than any president before or after him. At one time during James Madison’s presidential tenure, he even held two positions in the cabinet, as Secretary of State and Secretary of War.

Early in his life, Monroe met Jefferson when he was governor of Virginia. Later on, Jefferson became his private mentor and a lifelong friend, encouraging him to continue his journey in legal education. In 1780 Monroe reenrolled at William & Mary under the mentorship of Jefferson and moved to Albemarle County, Virginia, so he could live in the vicinity of his friend. His Highland estate actually bordered Jefferson’s Monticello.

In a letter he once wrote to Jefferson, Monroe stated: “I feel that whatever I am at present in the opinion of others or whatever I may be in future has greatly arose from your friendship,” which makes the fact that he also died on the same day as his friend, on the 4th of July, even stranger. He died in New York City from heart failure and tuberculosis in 1831, thus becoming the third and the last president to have died on Independence Day.