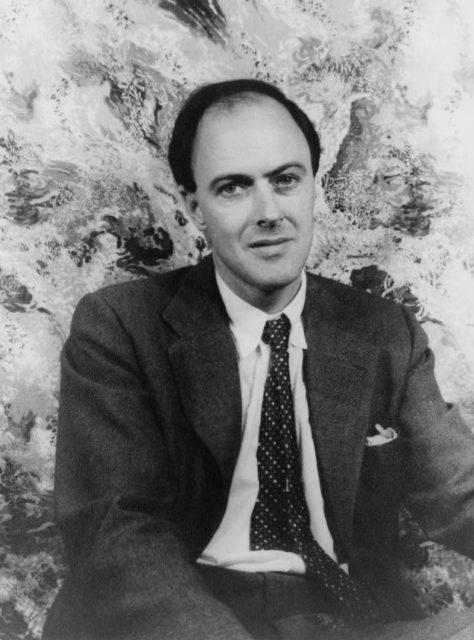

For many of us, the word gremlins sparks an image of strange, otherworldly, mischievous creatures from the 1984 film of the same name, produced by Steven Spielberg and directed by Joe Dante. However, the film was loosely based on a children’s novel written in 1943 by Roald Dahl. The author of not only The Gremlins but also Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, he’s the one who first turned the gremlins into a popular idea.

Thanks to the 1984 film, it is now widely supposed that gremlins are tiny and destructive impish monsters, who seem nothing but cute furry beings, before ravishing an entire community.

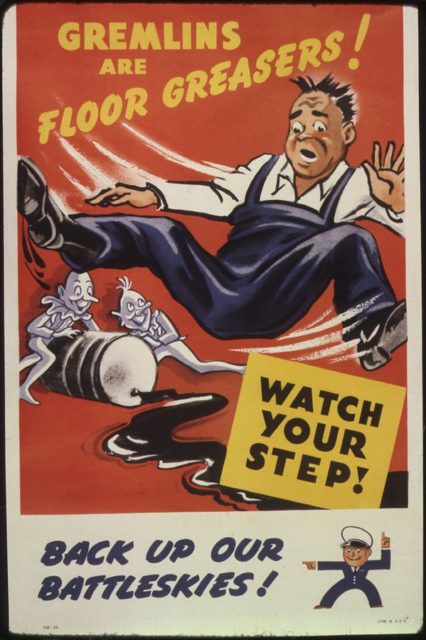

Gremlins are, in fact, supposedly real entities that caused mischief in the machinery and aggravated British pilots going back to the early 20th century.

It is believed that the word gremlin itself is derived from the Old English word gremian, meaning “to vex.” Another reference can be found in a book by Carol Rose, Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns, and Goblins: An Encyclopedia, in which the name is attributed to be a linguistic blend of the name of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and Fremlin Beer, once the largest brewery in Kent.

The gremlin is an utterly mischievous gnome-like sprite, typically represented as not more than a foot tall, whose origins are in folklore tales that tell of goblins and fairies. Ever since WWII, numerous imagined creatures have been referred to as gremlins. Their reputation: to harass an aircraft, cause havoc aboard and be the ultimate blame after an aircraft is brought down from the skies. Some early depictions mention that the impish devils had a natural urge to mess up machinery, hence why British pilots credited the breakdown of their aircrafts to the work of gremlins.

A notable early gremlin reference can be found in the British newspaper The Spectator, which reads: “The old Royal Naval Air Service in 1917 and the newly constituted Royal Air Force in 1918 appear to have detected the existence of a horde of mysterious and malicious sprites whose whole purpose in life was…to bring about as many as possible of the inexplicable mishaps which, in those days as now, trouble an airman’s life.”

By 1923, the belief in these otherworldly entities had grown, especially after a British pilot crashed his plane into the sea and blamed the accident to the gremlins. He alleged they sabotaged the craft’s engine, mishandled the flight controls, and ultimately caused the crash.

The story, of course, spread like wildfire among other pilots, who also began reporting of being attacked by the miniature devils. The stories persisted into the next decade, and in 1938 aviator and writer Pauline Gover would write in a book that Scotland is “gremlin country,” a mystical realm where gremlins would cause troubles by cutting the wires of aircraft to be flown by particularly new and inexperienced pilots.

An article by Hubert Griffith in April 1942 also speaks about the appearance of gremlins. It states the devilish creatures have been present for a few years already, and includes stories told from pilots who had engaged in the Battle of Britain in 1940.

Recollections of seeing gremlins came most from those pilots who needed to fly in high-altitude units. When something went wrong with the craft or an unexplainable event occurred during a mission, it was reportedly the gremlins to blame.

At one point, the creatures were even considered to have sympathy for the enemy, but evidence of more stories quickly showed that even an enemy aircraft would sometimes face similar puzzling mechanical problems. Gremlins apparently were creatures who acted on their own behalf and interests.

The strange occurrences led folklorist John Hazen to state that “the gremlin has been looked on as new phenomenon, a product of the machine age – the age of air.”

In reality, gremlins are –we hope–nothing more than the product of imagination, or even the hallucinations of pilots flying at high altitude. It was also a handy way to pass over the blame when anything mechanical went wrong.

For some experts, this gremlin blaming built up the morale of pilots. Author and historian Marlin Bressi would contemplate on the matter, saying that imaginary gremlins played a crucial part to the airmen of the British Royal Air Force.

He writes: “Gremlin tales helped build morale among pilots, which, in turn, helped them repel the Luftwaffe invasion during the Battle of Britain during the summer of 1940.”

Author Roald Dahl, who served in the Royal Air Force in the Middle East, is credited with propelling the concept of the gremlins out of the airmen’s circle. Dahl himself experienced an unintended crash-landing in North Africa. As his service ended during WWII, he went on to write his first children’s novel entitled The Gremlins.

He would depict gremlins as little men who thrived on RAF fighters. Their wives were designated as “Fifinellas,” the male children as “Widgets” and the female ones as “Flibbertigibbets.” The book was sent to Walt Disney in July 1942. Disney developed a film project, and there was also a story published in an issue of Cosmopolitan magazine.

Disney would also publish several more issues about gremlins in Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories. Here, the gremlins were portrayed as tiny flying humans who inhabited their own village, and the main character was that of Gremlin Gus. His inputs certainly made gremlins more and more famous worldwide.

Related story from us: To make it more frightening, H. R. Giger designed an Alien with no eyes

In the meantime, pilots coming back from the war kept on reporting unusual occurrences with gremlins. After the war ended, the mystery was explained by experts who claimed gremlins were nothing more than the result of stress during combat and flying at great heights in the skies.

And that’s how the world really got a new imaginary friend (or foe) — that of the impish little devil called gremlin.