The most feared opponent in any military conflict is the sniper. This sharpshooter can remove an enemy target from a distance with uncanny accuracy, and is both hated and feared for it.

The term “sniper” stems from the British hunting of snipe, a game bird, in India in the 1770s. This bird is characterized by its timidity, its almost perfect camouflage, and its erratic flight patterns. Flushing and then shooting this bird was extremely challenging, and only the best marksmen were successful. The word “sniper” was not used in the military to designate a sharpshooter until the 1820s.

Traditionally, the role of sniper had been filled by men, as no women served in a combat role in the armed forces in Western Europe or North America. But all that changed with the advent of World War II.

The countries involved in the war found that they had to evolve the traditional view of women’s roles. With men being called upon to fight, women began taking jobs in industries that had traditionally been reserved for men. The next step: women taking up combat roles within the resistance and the regular forces.

When the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded Russia, the Red Army suffered huge losses in both personnel and equipment. At this stage, the military hierarchy knew that they had to change their view on the role of women and recruit them into the ranks of the military. Estimates indicate that some 800,000 women were recruited, and most filled traditional roles of nurses, drivers, cooks, or clerks. But a select few, 2,000 in all, were assigned the deadly duties of a sniper – a role at which they excelled.

Russian Major General Morozov said that the Russian military hierarchy believed that women were more patient, careful, and deliberate, and as they had smaller and softer hands than men, they squeezed the trigger better. This all added up to making them superior snipers. Many of these women fulfilled their superior’s faith in their abilities and became feared snipers, targeting German officers and field commanders that the Germans found difficult to replace, thus leaving the German troops leaderless.

One of the most feared and lethal female snipers was Lyudmila Pavlichenko, a Ukrainian national who was born in a tiny village outside Kiev. When she heard one of her neighbors bragging about his shooting skills, her competitive instinct kicked in, and she taught herself to use a rifle. The German invasion came while she was studying for her master’s degree in history at the University of Kiev; she immediately left her studies and enrolled in the army.

The recruitment office tried to enroll Pavlichenko as a nurse, but she insisted on a combat role. She was sent to a small hill that was being defended by the Red Army, where a rifle was placed in her hands and she was told to shoot two Romanians that were assisting the German forces. Both targets were at a distance, but she effortlessly took them down. She was immediately sent to the 25th Chapayev Rifle Division.

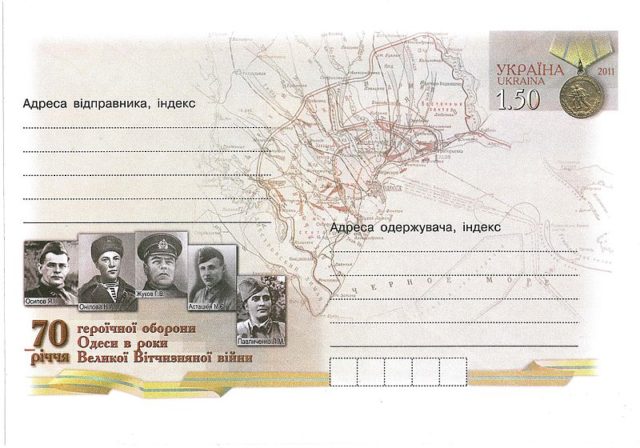

Pavlichenko served in both Odessa and Moldavia before being sent to Sevastopol. Her legendary skill had earned her the nickname “Lady Death”. She was often tasked with counter-sniping, one of the most dangerous assignments. In this role, she would attempt to pick off the German snipers – a duel that could last several days. Her reputation grew to such an extent that the Germans tried to get her to defect by using a loudspeaker to entice her with offers of chocolate and the rank of an officer. In less than a year of combat duty, she was credited with 309 kills, including 36 German snipers. This tally makes her one of the deadliest sharpshooters in the history of warfare.

After being wounded four times, the last time taking a faceful of shrapnel, she was pulled from the front line to train new snipers and to undertake a tour of America, Canada, and Great Britain to promote the war effort. While touring in America with Eleanor Roosevelt, she was frustrated when constantly bombarded with questions asking if she wore makeup into battle, or what her views on fashion or hair styles were for military personnel. She held up well, but eventually her patience wore thin; she felt that she was seen as a curiosity and a subject for newspaper headlines rather than a citizen, soldier, and fighter for her country. Eventually, in a speech given in Chicago in 1942, she said, “Gentlemen, I am 25 years old, and I have killed 309 fascist occupants by now. Don’t you think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?”

On her return to Russia, she was rewarded with the Hero of the Soviet Union, her country’s highest honor, and she was promoted to major. She continued to train snipers for the remainder of the war; when peace was declared, she went back to her university studies to finish her degree. After this, she worked as an historian.

Females have continued to take on combat roles in many armed forces around the world today. They have comported themselves with honor.