Reality and fiction often intertwine in literature. It is almost impossible to create something truly original that is not in some way based on or inspired by an event that actually occurred in the past, or by the worlds imagined by a writer working in the past. Authors also create a representation of a possible reality they’ve imagined as occurring some time in the future.

While the latter is the definition of science fiction, in which the storyline is often presented as one possible reality resulting from a contemporary state of affairs, the former is a reimagining of something that already has happened, told by the storyteller from a particular take on history. History and fantasy have had a long and close relationship for eons, and authors of the genre are clearly inspired by the historical literature of the past, particularly from the medieval period.

In fact, many authors more or less openly talk about the inspirations behind their stories. By doing so, they often bring more depth and emotion to the reader’s or viewer’s experience of the story and its characters. For instance, George R. R. Martin, the famous writer of the A Song of Ice and Fire epic fantasy series, stated that although the world and its characters in the books are fictional, they are greatly inspired by significant events that took part in Medieval Europe. Unfortunately, he’s never clarified his statements with any details.

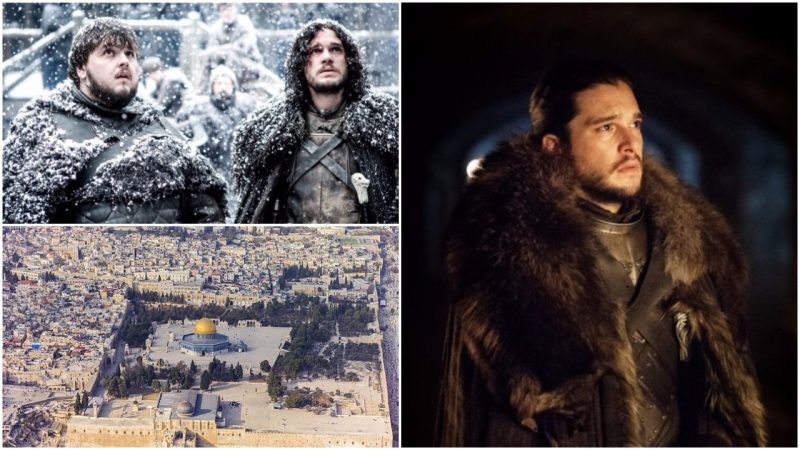

So, with the premiere of the brand new and highly anticipated season of the HBO series Game of Thrones–its premiere is scheduled for the 16th of July in the United States –we aim to provide some insight into the inspiration and the historical background of some of the groups and characters in the series.

Let us start with the Night’s Watch and the Keepers of the Realm of Men.

First things first, the Night’s Watch is a sworn brotherhood of men who chose not to take part in politics nor hold an allegiance to any king and instead dedicated their lives to protecting the realm of men from threats beyond the great Wall, the gigantic ice structure placed on the northern border of the Seven Kingdoms. They are here either to clear a name tainted by wrongdoings and criminal activities or to live a glorified life serving humanity as the first fighting force when winter arrives.

And they have. Formed after the Long Night and the Battle for the Dawn, the Watch has continuously defended the Wall for centuries. When a man decides to join the order of the Night’s Watch, he is first considered as a new recruit and spends some time training in the rigorous traditions of the Watch. If he volunteered, he may leave during this period at any time, but if he chose the Watch instead of the death penalty, given for criminal activity (which most of them have), deserting the ranks is punishable by death. Once the recruitment period is completed and the recruit takes the vow, he becomes a sworn brother and can never leave the Watch, ever.

This romantic notion of a group of outcast knights roaming on the edges of civilization, men who took a binding oath to protect the society they left behind, is not uncommon. Evidence points to more than one secret order or special militia purposefully formed in the shadow of some greater threat.

You can compare them to the Roman legions that manned Hadrian’s Wall (which, by the way, is the inspiration for the 700 foot tall and 300 miles long Wall we see in the series); the Hospitallers, a medieval Catholic military order also known as the Order of Saint John; and the secret military order formed to defend Christianity during the Crusades, known as the Teutonic Order.

And if we put the religious element aside, the Night’s Watch is somewhat like these medieval holy orders (although brothers of the watch are sworn to protect all men). They renounce possession of any lands or titles, take no wives nor father children, swearing that they will live and die to defend the realm.

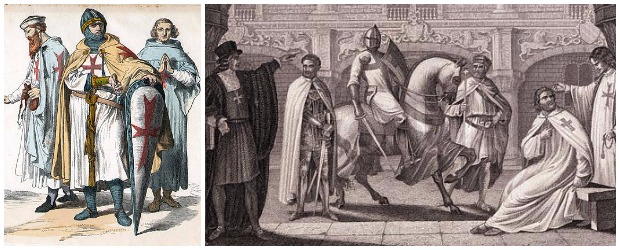

Some historical holy orders have held very similar views on protecting groups against the hostile attacks of other religions. Yet none can equal the resemblance of the Night’s Watch to one of the most important and secretive of fighting orders of them all, the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, more commonly referred to as the Knights Templar.

From origins and purpose to military structure, leadership, and oath giving, the Watch appears to be Martin’s version of the extremely powerful and highly skilled fighting unit.

For instance, the Knights Templar were formed at the very beginning of the 12th century, as a small band of nine knights resolved to patrol the roads of the newly captured Holy Land and make it safe for pilgrims who would take the dangerous journey from Europe. Europeans of the First Crusade recovered Jerusalem from Muslim forces in 1099 after a long 400 years under their rule, a fight easily comparable to the War for the Dawn in GOT, a war that arose from the Long Night, a winter so long that it lasted for almost a generation, during which White Walkers fell upon Westeros intending to bring an end to all life and cover the world in an endless winter.

Although Jerusalem was secured, the rest of the land was not. So in 1118, Ser Hughes de Payens proposed to King Baldwin II that he establish a monastic order in order to protect the pilgrims from the bandits (wildlings) who prayed on them. Medieval Christianity understood the advantages of harnessing military power for particular objectives, so the Knights, with the support of a leading Church figure, the powerful Bernard of Clairvaux, were given a headquarters near the assumed site of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, from which they took their name.

Soon after, the Templars were heavily sponsored by the Church and as a consequence started to receive money, land, castles, and sons from noble families who were eager to help the cause in the fight for the Holy Land. Starting only with nine knights vowed to poverty, with Bernard’s backing and financed by the Church (the Night’s Watch had their fair share of gifts from the Northmen), they rose to be an extremely influential financial and military force, and one to be reckoned with. Starting from Temple Mount, the Knights Templar soon had headquarters all around Europe and the Middle East, and nobles, as well as criminals who wished to escape conviction and to beg forgiveness for their crimes from God, joined their ranks in search of purification.

Similarly, when first established, the order of the Night’s Watch was highly regarded and attracted volunteers from noble houses all around the seven kingdoms and the free cities. To be a “Crow” was the greatest honor and a sign of selfless devotion to the protection of the realm. Later on, criminals who would wanted to escape punishment, nobles avoiding scandal, and other social outcasts started joining in, where they were given a clean slate and a fresh start as long as they lived by the rules of the order. They grew in such numbers that they soon had to be organized.

Structurally, the Men of the Night’s Watch are divided into three different orders: the Rangers, the Builders, and the Stewards, led by their Lord Commander, who was appointed for life and replaced after his death by someone who would win the majority of votes. For comparison, the Knights Templar also had three divisions, the Knights themselves, the Sergeants, and the Chaplains, all under the command of a Grand Master, also appointed for life, starting with the founder Hugues de Payens.

Whereas the noble Knights, as the prime fighting force, represent the Rangers in the Night’s Watch, the Sergeant’s role in the Templars is analogous to that of the builders and the stewards, as the ones who provide support and services to the order. The Chaplain’s role was the one given to Maester Aemon in Game of Thrones, as wisest of men, one who best understands the ideology of the order. In one instance, Aemon famously says to one of the series’ principal characters: “Tell me, did you ever wonder why the men of the Night’s Watch take no wives and father no children?” “No.” “So they will not love… love is the death of duty.”

And this sentence best describes the essence of the Night’s Watch, as it does, too, of the Knights Templar. In both, recruits who joined the ranks had to renounce everything they’d ever cherished or loved, to renounce completely their previous life, their heritage, family or historical background, thus giving them a chance to start a new chapter in their lives in total service to their brothers in arms, the order and the vows they choose to live and die for.

“Night gathers, and now my watch begins. It shall not end until my death. I shall take no wife, hold no lands, father no children. I shall wear no crowns and win no glory. I shall live and die at my post. I am the sword in the darkness. I am the watcher on the walls. I am the fire that burns against the cold, the light that brings the dawn, the horn that wakes the sleepers, the shield that guards the realms of men. I pledge my life and honor to the Night’s Watch, for this night and all the nights to come.”

And if we dig a little deeper, we encounter something similar in one of the oldest monastic orders, that of the Benedictines, which was later adopted by Bernard and Hughes when composing the rule for the Knights Templar: “I pledge myself, from now and forever, to the holy Militia of the Order of the Temple. I declare to take freely and solemnly an oath of obedience, poverty, and chastity, as well as fraternity, hospitality, and preliation.”

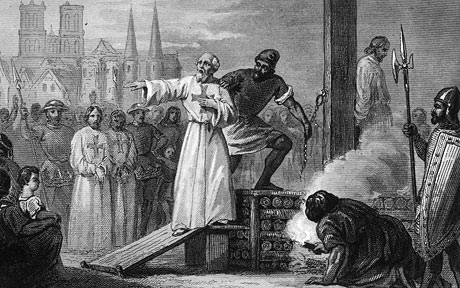

In both orders, known for their strict rules, desertion of any kind from its ranks and a breaking of the oath given when recruits entered the order was punishable by death. At the very start of the 14th century, the order of the Knight’s Templar was accused of financial corruption, fraud, and secrecy.

During those days, many of the Templars charged with such crimes as idolatry, treason, homosexuality, and spitting on the cross were burned at the stake in Paris along with their elderly Grand Master Jacques de Molay, ironically by the same church they had solemnly sworn to protect. We are yet to see downfall of the men who “took the black.”