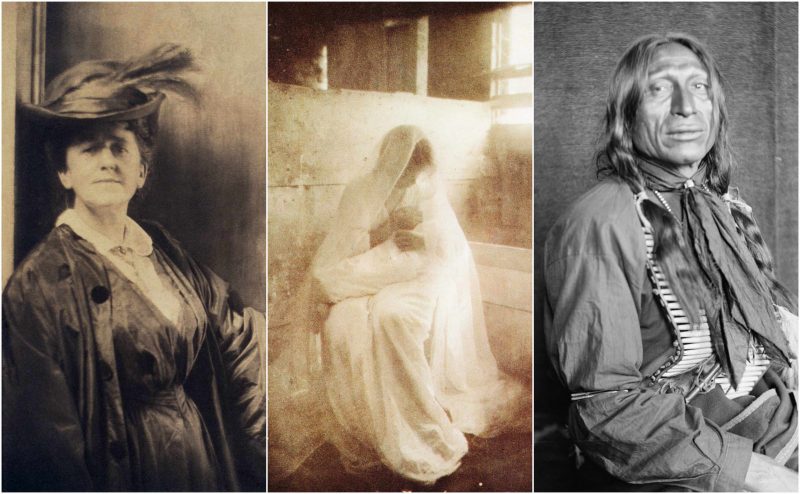

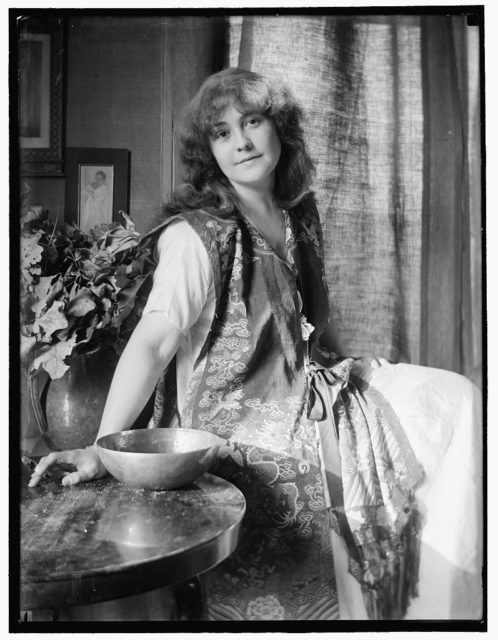

She started studying art at the age of 37 and went on to produce beautiful photographs. One of her works sold for $100, which was the highest price paid for a photograph at the time. Before turning her interest to art, Käsebier was a housewife, raising her children. Although she was financially supported by her husband, it was, as she later stated, an unhappy marriage. She defied the norms concerning age and gender in 19th century American society, leaving a fine body of work as her legacy.

Käsebier was born in Iowa in 1852. When she was 22, she married Eduard Käsebier, a 28-year-old Brooklyn businessman. They had three children and raised them in their new home on a farm in New Durham. They lived together for almost 10 years, a period to which Gertrude later referred as “miserable,” saying that “If my husband has gone to Heaven, I want to go to Hell. He was terrible… Nothing was ever good enough for him.”

Because of the scandal that a divorce would cause, the couple decided to remain married but to live separate lives. Despite their differences, Käsebier supported Gertrude financially when she decided to enroll in an art school at the age of 37. It was the early 1880s, and later on, Gertrude could never specify the reason that sparked her interest in art. But she devoted herself to her studies with full passion.

In 1889, the future photographer moved back to Brooklyn, along with her kids, despite her husband’s objections. She was eager to learn more, and in Brooklyn, the Pratt Institute of Art and Design had just been founded. Käsebier attended a full-time program, and one of her teachers there was Arthur Wesley Dow, a photographer and influential arts educator. He introduced Käsebier to art circles and would later help in the promotion of her career.

Initially, she studied painting and drawing, but she soon fell in love with photography. In the early 1890s, following the tradition of the art student, Käsebier traveled to Europe to augment her education. In 1894, she went to Germany for a few weeks, leaving her daughters with relatives in Wiesbaden, and studied the chemistry of photography. Then she moved to France, where she remained until the end of the year.

She returned to Brooklyn in 1895 and decided to become a professional photographer, partially because she had to earn some money as her husband had become seriously ill and couldn’t afford to pay for her further education. Just a year later, Käsebier became the assistant in the studio of Samuel H. Lifshey, a portrait photographer from Brooklyn from whom she learned how to run a studio.

Just a year later, she had an individual exhibition of 150 photographs at the Boston Camera Club and later at the Pratt Institute. That same year, she was invited to exhibit her collection at the Photographic Society of Philadelphia. At the same time, she began actively promoting photography as a career for women, encouraging artistic women to study and explore the artform.

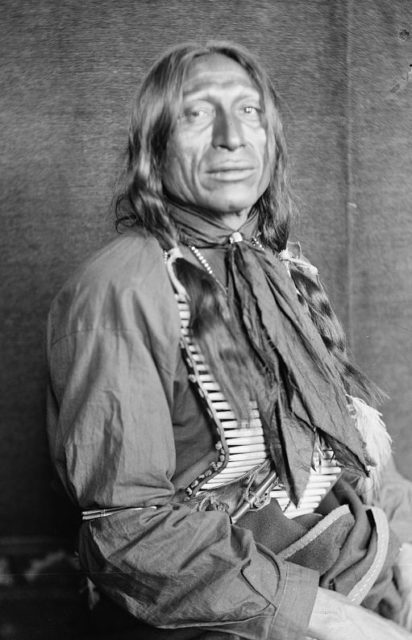

In 1898, while in her studio on Fifth Avenue, Käsebier observed the troupe parade of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. It inspired her to send a letter to William “Buffalo Bill” Cody with a request to photograph the members of the troupe who were of the Lakota Sioux people. She was given permission by Cody and started her project, which was to be purely artistic, and the images were not to be used commercially, and were never used on the promotional posters or the booklets of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West program.

Käsebier’s photographs of the Sioux were classical portraits taken while they were feeling relaxed. Among some of her most famous photographs were the portraits she made of Chief Flying Hawk and Chief Iron Trail, now preserved at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Museum of American History’s Photographic History Collection.

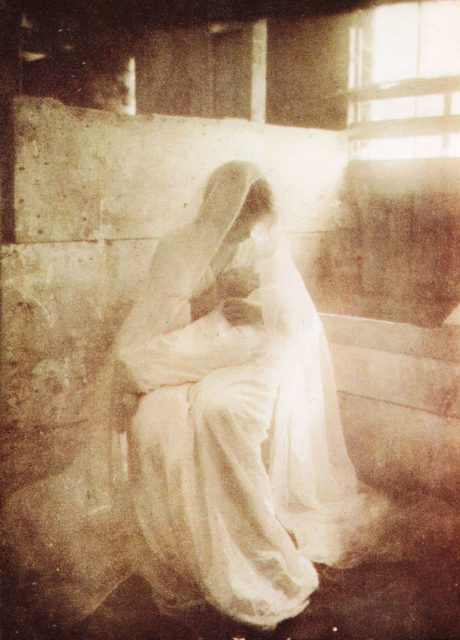

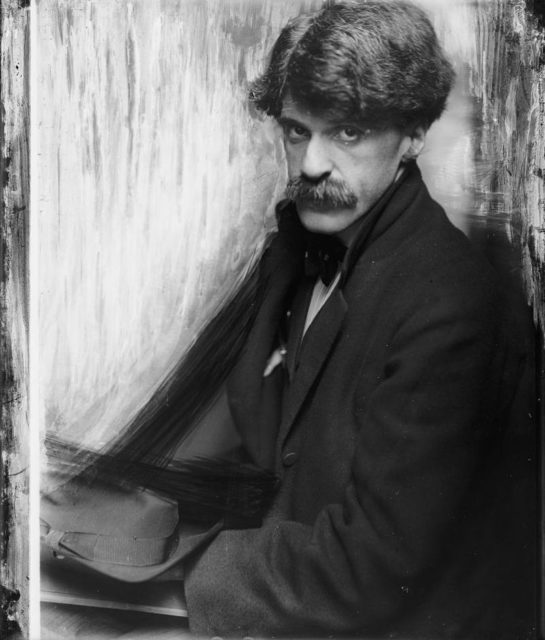

In 1899, five of Käsebier’s photographs were published in Camera Notes by Alfred Stieglitz, who declared her the most significant artist of portrait photos of the day. She had a rapid rise to fame, being praised by many influential art critics of the time. That same year, Käsebier sold a print of “The Manger” for $100, a price never before paid for a photograph. In 1900, in a Newark (Ohio) Photography Salon catalog, she was called “The US’ foremost professional photographer.” Later that year, Käsebier became one of the first two women to be elected to Britain’s Linked Ring.

Over time, her friendship and professional relationship with Stieglitz became strained because of their opposing ideals and beliefs. Käsebier saw photography and art as paid work and depended on it while her former friend had the opposite idea that art shouldn’t be commercialized. Stieglitz even criticized her publicly and tried to turn other admirers of Käsebier’s work against her. However, there were many who supported her and many whose careers she inspired, such as Laura Gilpin, Consuelo Kanaga, and Clara Sipprell.

In 1929, Käsebier gave up her practice altogether, emptying her studio. She was given a major, individual exhibition at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, which was to be her last. Gertrude Käsebier died at the age of 82, in the home of her daughter, Hermine Turner, who had taken up her mother’s profession, portrait photography.

Related story from us: Robert Capa, called “the greatest war photographer in the world”

Today, a major collection of Käsebier’s work can be seen at the University of Delaware.