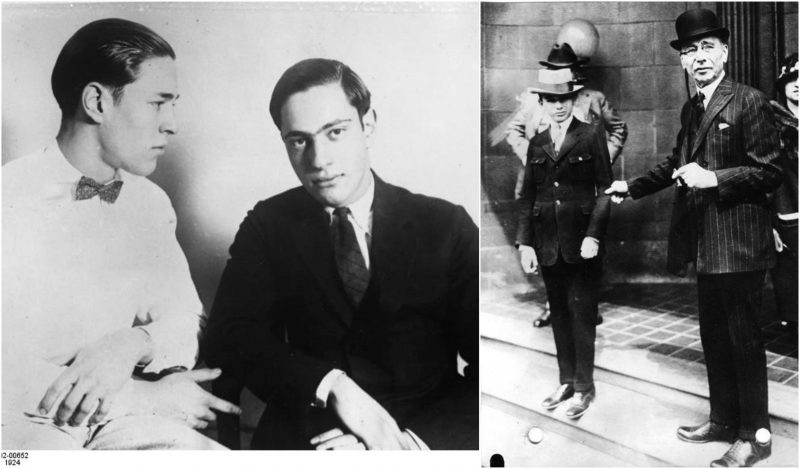

Leopold and Loeb were two teenagers, ages 19 and 18 respectively, whose obsession with Nietzsche’s idea of “Übermenschen” motivated them to commit a horrific crime. The German term translates to “Supermen” and refers to the concept of a person who, due to his superior intellect and unique capabilities, is above the law itself; to him, morality and human ethics don’t apply.

The two boys felt that they were extraordinary humans of just this kind and could do whatever they desired. It was not long into their friendship before they set their sights on committing “the perfect crime.” Their victim was to be a 14-year-old boy, Robert Franks, who they brutally murdered in the spring of 1924.

Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb were born to very wealthy families in Chicago, as was their victim, Franks. Leopold was born in November 1904 and was considered a child prodigy. He reportedly studied 15 languages, 5 of which he spoke fluently. Even though the IQ tests of that period can’t be directly compared to the modern ones, Leopold scored a quotient of 210.

By the age of 19, he already had his undergraduate degree with Phi Beta Kappa honors from the University of Chicago and planned to travel in Europe before beginning his studies at Harvard Law School. Leopold was also nationally recognized as an ornithologist and along with a few other ornithologists, he identified an endangered songbird, the Kirtland’s warbler, that hadn’t been observed in the area of Chicago for more than 50 years.

His friend Richard Loeb was the son of Albert Henry Loeb, a wealthy lawyer and former vice-president of Sears, Roebuck & Company. Loeb was also extraordinarily intelligent. At the age of 17, Loeb graduated from the University of Michigan, becoming its youngest graduate. He was, however, described as lazy and unmotivated, with the only thing that excited him being the detective novels he was reading.

Leopold and Loeb had known each other since their childhood, but they became friends while attending the University of Chicago, especially after they discovered that they had a shared interest in crime. Leopold introduced Loeb to his idol, Friedrich Nietzsche, and the concept of supermen and he convinced him that Loeb was, like himself, one of these extraordinary and unaccountable individuals. In a letter that Leopold sent to Loeb, he wrote that such an extraordinary person as the “Übermenschen” is not liable for anything that he might do.

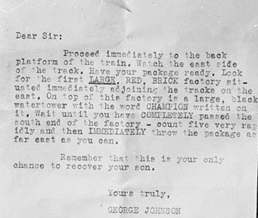

They were certain that normal restrictions did not apply to them due to their intellect, and so they started committing deviant acts such as vandalism and small robberies. They even broke into the fraternity house of the university and stole a camera, penknives, and a typewriter that they would later use to write their ransom note. However, dissatisfied with the poor media coverage of their acts, they started thinking about something bigger and more “significant.” They decided to commit a murder.

The boys settled on the idea of murdering a young boy as their perfect crime. It took them seven months to plan the whole process, starting from the method of abduction and progressing to how they were going to dispose of the body. They decided to obscure the case by asking for money from the family of the boy and used the typewriter that they stole from the university to type their final set of instructions.

Their search for a victim took them a while, however, since they were limiting their choice to the students from the Harvard School for Boys where Loeb used to study. In the end, they chose Loeb’s second cousin, Robert “Bobby” Franks, the son of Jacob Franks, a watch manufacturer from Chicago. Bobby lived across the street from Loeb and used to play tennis at his home.

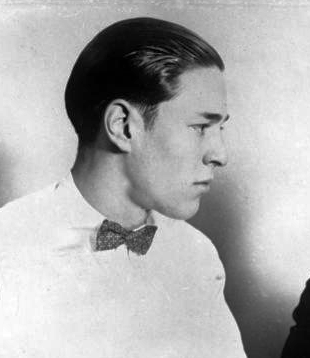

It was May 21, 1924, when they set in motion their meticulously thought out plan. First, Leopold rented a car using the name “Morton D. Ballard,” which they then drove to the school that Bobby attended and waited for him outside in order to offer him a ride. Franks refused the offer as he was too close to home, but Loeb was persuasive and told the boy that he wanted to discuss a new tennis racket he’d bought. Although it was never revealed what happened exactly, according to the majority of investigators and detectives who studied the case, it was Leopold who was driving and Loeb who sat in the back seat holding a chisel, the boys’ weapon of choice.

Franks sat in the front passenger seat, while Loeb, who was sitting behind him, struck the boy in the back of the head. It is speculated that he then dragged the victim into the back seat and choked him to death. The dumping spot, they had previously determined, was to be Wolf Lake in Hammond, Indiana, 25 miles away from Chicago. It was after nightfall when they discarded the boy’s clothes, and before leaving the body in a culvert, they poured hydrochloric acid on the boy’s face, on a distinctive abdominal scar, and also his genitals, the latter to supposedly hide the fact that Franks was circumcised.

When they disposed of the body and all of the evidence, the two murderers returned to Chicago, where there was already word of Franks’ disappearance. Introducing himself as “George Johnson,” Leopold called Franks’ family and said that the boy had been kidnapped, followed by sending them the typed ransom note. The boys then decided to spend the rest of the evening playing cards. During the following days, they gave instructions to Franks’ family dictating where and when to drop the money. The plan was stalled, however, when a family member, stressed and afraid, forgot the address where he was supposed to leave the money, and in the meantime, a man named Tony Minke had found the young boy’s body.

Leopold and Loeb burned the robe that they used to move the body and destroyed the typewriter. They were convinced that everything was done properly and that they could continue on with their lives without ever being caught. This, however, was not to be, and while Loeb went on with his usual daily routine, Leopold was offering theories to reporters and even to the police. He actually said in front of one police officer that if he were to kill somebody, it would have likely been that “cocky little son of a bitch, Bobby Franks.”

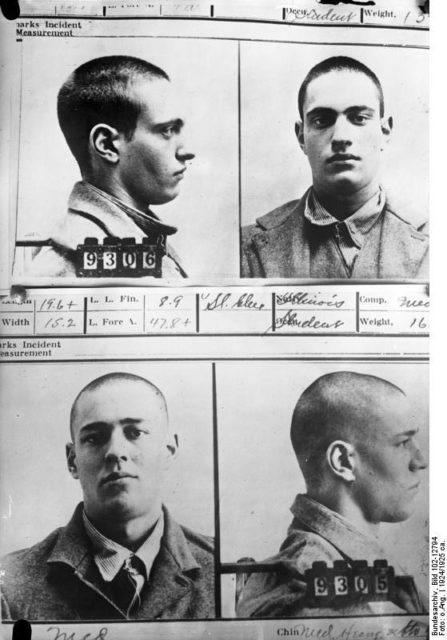

Their fatal mistake: A pair of eyeglasses was found at the crime scene and although the frame and prescription were quite common, they had an unusual hinge mechanism that was ordered by only three people in Chicago, one of them being Nathan Leopold. When he was questioned by the police, Leopold said that there was a possibility that he had dropped his glasses when he went on a bird-watching trip. Soon after, the destroyed typewriter was found, and on the 29th of May, Leopold and Loeb were summoned for formal questioning, only eight days after their “perfect crime.”

They both claimed that on the night of the murder they drove around Chicago in Leopold’s car and picked up two women, May and Edna, but they didn’t remember their last names. Leopold’s chauffeur, however, told the police that on that particular night he was repairing Leopold’s car. This claim was later confirmed by the chauffeur’s wife.

Although Leopold was the one eager to talk to the police, it was Loeb who confessed first, accusing his friend of being the main organizer of the whole thing. He also claimed that it was Leopold who killed Franks while he, Loeb, was driving the car. It could never be confirmed with any certainty who murdered the boy, but Leopold later claimed that Loeb wrote to him saying, “Mompsie feels less terrible than she might, thinking you did it,” and that that was the reason why he wouldn’t confess. In fact, most observers believe that it was Loeb who did it but conversely, an eyewitness, Carl Ulvigh claimed that just minutes before Franks got in the car, it was Loeb who was driving the vehicle.

They both admitted that the thrill of the kill motivated and obsessed them. They even explained their Übermensch delusions and tried to justify their drive for the “perfect crime.” Leopold told his attorney that “the killing was an experiment” and that if one understands, it would be easy to justify such a killing of a beetle on a pin done by an entomologist.

Their trial lasted for 32 days. Their attorney, Clarence Darrow, eventually had them plead guilty but worked hard to persuade the judge to not give them the death penalty. Medical experts testified to the boys’ strangeness. One doctor said of Loeb that “he was the host of an infantile emotional makeup which was a long way from the possibility of functioning harmoniously with his developed intelligence….he is still a little child talking to his Teddy bear.”

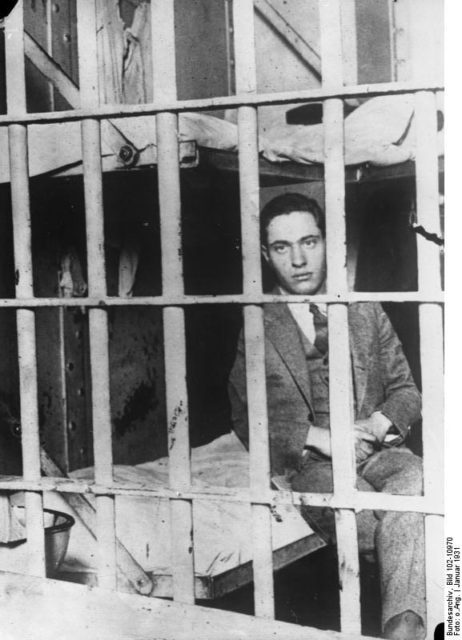

Both Leopold and Loeb were sentenced to life imprisonment plus 99 years. They were sent to Stateville Penitentiary, where they remained close friends. Even though it was assumed that they were receiving sums of money from their families, in fact, they were receiving only $5 per week. They were seen as rich snobs, and this caused them many troubles with the other inmates. On January 28, 1936, Loeb was attacked with a straight razor by his former cellmate.

Leopold, who witnessed the attack, desperately tried to save his friend and took him to the prison hospital. After Loeb had died, as an act of affection, Leopold washed his body.

After this death, Leopold became a model prisoner. He learned and mastered an additional 12 languages on top of the ones that he already spoke and he made significant contributions at Stateville Penitentiary, such as the reorganization of the prison library, teaching the students in the school, and volunteering in the prison hospital.

He served 33 years in jail, and after many unsuccessful parole petitions, he was eventually released in 1958. He moved to Puerto Rico where he worked as a technician in a hospital. He also married a widow, a florist with whom he remained until his death in 1971. He died of a diabetes-related heart attack.