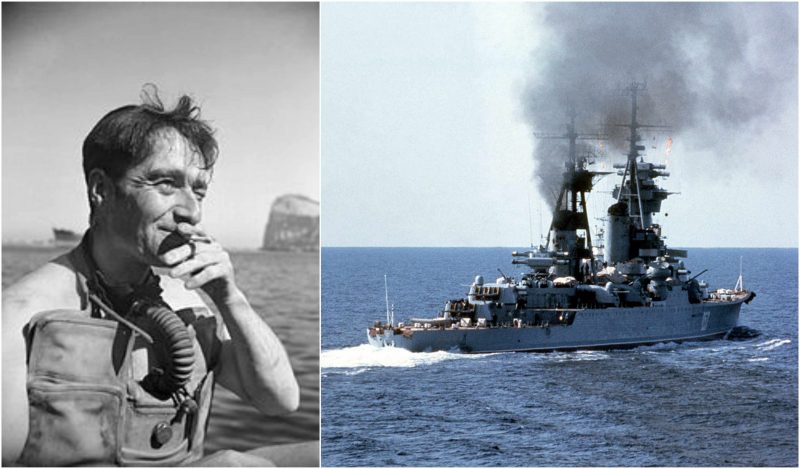

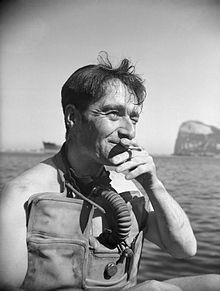

Lionel Kenneth Phillip Crabb was an MI6 diver and a Royal Navy frogman who disappeared in 1956 while investigating underwater a Soviet cruiser, Ordzhonikidze, anchored at Portsmouth Dockyard. His vanishing led to many conspiracy theories, and it inspired Ian Fleming to write the 1961 James Bond adventure Thunderball.

According to some of the numerous theories, Crabb had been murdered (even decapitated) immediately near the ship or first captured, questioned, and then killed. Others believed that he might have been brainwashed by the Russians and made part of the Russian Navy. There was also a theory that he was a double agent, or the less exciting possibility that he had a heart attack and died underwater. Whatever the truth, it is not revealed what happened to the agent to this day.

Lionel Crabb was born to a poor family in southwest London in 1909. His financial situation forced him to work different jobs until he completed his two-year training at the school ship HMS Conway for a career at sea. Then he joined the merchant navy. At the beginning of World War II, Crabb was an army gunner, but in 1941 he became a party of the Royal Navy. After only a year, he was assigned the challenging and dangerous task of removing limpet mines that Italian divers had attached to Allied ships at Gibraltar. His job was to disarm the mines that were removed by the British divers, and in the meantime, he learned to dive.

He soon joined the divers who were checking the Gibraltar harbor for limpet mines. This was during the period of Italian frogmen and manned torpedo attacks by the Decima Flottiglia MAS. In December 1942, two Italian frogmen died, probably killed by depth charges. After their bodies were recovered, Commander Lionel Crabb and his partner, Sydney Knowles, took the frogmen’s swim fins and Scuba sets and used them from then on.

Back at home, Crabb was awarded the George Medal and promoted to lieutenant commander. After a year, he became Principal Diving Officer for Northern Italy, and his assignment was to clear the port of Venice and Livorno of mines. Later he was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for his services in Italy. In 1943, Crabb was also an investigating diver of the suspicious death of General Sikorski of the Polish Army, whose aircraft crashed near Gibraltar. Around this time, he earned his nickname “Buster,” after the American swimmer and actor Buster Crabbe.

When the war ended, he was stationed in Palestine, where he led the team that worked on disposal of explosives set by divers from the Palmach sea force, Palyam, during the years of Mandatory Palestine. In 1947, Crabb was demobilized from the military and moved to a civilian job, exploring the wreck of a 1588 Spanish galleon on the Isle of Mull. He eventually returned to his post at the Royal Navy, diving twice to explore the submarines HMS Truculent in 1950 and HMS Affray in 1951.

In 1955, along with Sydney Knowles, Crabb investigated the Soviet cruiser Sverdlov to evaluate its superior maneuverability. Knowles later revealed that at the ship’s bow, they found a circular opening and inside it a huge propeller that could be directed to give thrust to the bow. That same year Crabb retired, but he was recruited for a mission by MI6 the following year, even though his smoking and drinking took their toll on his health and he was far from the shape he used to be during World War II.

MI6 assigned him the task of investigating the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze, which brought Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev to Britain on a visit. The Soviets were rumored to have made strides with propellers and underwater sonar, and here was one of their ships in British waters. Prime Minister Anthony Eden had told the nation’s secret services not to execute any secret missions underwater while the Soviets visited for reasons of diplomacy–“These ships are our guests”–but he was ignored.

On April 18, 1956, Crabb supposedly went on a bender and drank five double whiskeys with friends. The next morning, Crabb secretly dove into Portsmouth Harbour to take a closer look at the cruiser. His MI6 handler never saw him again. Ten days later, the news about his disappearance during a possible underwater mission was all over the media.

MI6 attempted to cover up this espionage mission. Anthony Eden was upset that MI6 had operated without his consent. The newspapers published stories that Crabb had been captured and then taken to the Soviet Union. The Soviets released a statement that their crew at Ordzhonikidze had spotted a frogman near the cruiser on April 19.

Almost 14 months after Crabb’s disappearance, a body in a diving suit was found by two fishermen in Chichester Harbour, and it was brought to shore by members of RAF Marine Craft Unit No. 1107. The corpse was missing its head and both arms, and it was impossible to identify it with the technology of the time. Rob Hoole, a British diving expert, said that the body found had Crabb’s height and body-hair color, and was dressed in the same clothes. He also thought that there was “nothing sinister” about the looks of it considering the time it had spent in the water.

Nobody could identify the body, neither Crabb’s ex-wife nor his girlfriend. In the end, Sydney Knowles was asked to do so. He carefully examined the body, searching for a prominent scar on the left thigh and a Y-shaped one behind the left knee. Since he couldn’t find any scars, Knowles stated that the body was not Crabb.

Read another story from us: Sir Roger Moore, the longest-serving James Bond, dies at 89

There were many theories. The mystery of his disappearance inspired crime-fiction literature. In Thunderball, when Bond investigates the hull of the Disco Volante, Fleming, himself an officer in British Naval intelligence, was directly inspired by Crabb.

In his 2014 nonfiction book, A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal, author Ben Macintyre wrote that Kim Philby, recruited at Cambridge to become a spy for the Russians in the 1930s, became aware of Crabb’s mission through his friends at M16 and most likely warned the Soviets ahead of time. “Aboard the Ordzhonikidze the Soviets were waiting,” Macintyre wrote.

In 2007 a retired Soviet sailor had come forward to relate what happened. On the morning of the 19th, the sailor was ordered to “dive beneath the ship and patrol for any spying frogmen.” Kolstov said he spotted just such a frogman and cut his throat. The sailor was later awarded a medal.

It is impossible to confiirm if that is indeed what happened to Crabb. His fate is still essentially a mystery.