The stereotype of the Victorian wife is elegant, pious, feminine, modest, and caring only for others. Submitted for consideration are four ladies of another kind.

Adelaide Blanche de la Tremoille

In 1886, a case known as the “Pimlico Mystery” occurred in London, when Adelaide Blanche de la Tremoille was accused of poisoning her husband, Edwin Bartlett. At the heart of the mystery was the strange relationship between Bartlett, a wealthy grocer, his 10 years’ younger wife, French-born Adelaide, and her tutor and spiritual counselor, the Reverend George Dyson. It was a triangle that didn’t end well.

According to Adelaide’s story, she had a romantic relationship with Dyson, which was encouraged by her husband, Edwin. On New Year’s Eve in 1885, Edwin was found dead in bed next to his wife, and the autopsy showed that his stomach was full of liquid chloroform. Less than a month earlier, Adelaide asked Dyson for some chloroform, which was supposedly prescribed by Edwin’s doctor, Alfred Leach. Instead of buying one large bottle, Dyson purchased four small bottles of chloroform from four different shops.

Both Adelaide and Reverend Dyson were arrested, but the charges against the latter were dropped soon after. What remained a mystery was how the chloroform got into Edwin’s stomach without burning his throat or windpipe. This fact served as Adelaide’s primary defense, and afterward, she was acquitted due to the lack of evidence.

Sir James Paget, an English pathologist, and surgeon, reportedly said that, as Adelaide was free and couldn’t be tried again, she should tell the world how she did it, for the sake of science. However, nothing is known about Adelaide and Dyson’s lives after the trial and the case continues to be a mystery, having inspired many stories, and of course, speculation.

Madeleine Smith

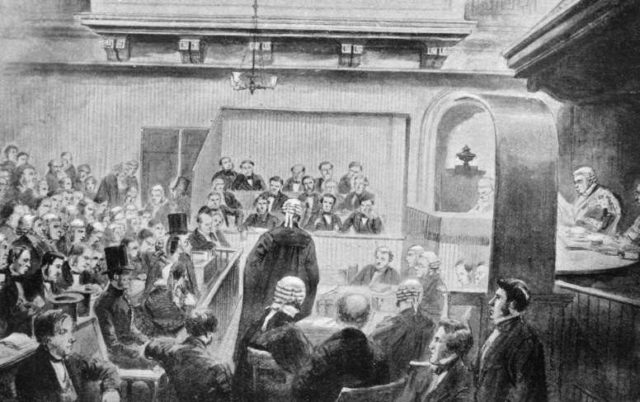

Beautiful Madeleine Smith was a Glasgow socialite. She was 21 and having an affair with a clerk, Emile L’Angelier, with whom she exchanged some very passionate letters. Unaware of her affair, Madeleine’s parents promoted her engagement to a friend of her father’s, which she was enthusiastic about, and she hurried to end her relationship with L’Angelier. However, he wasn’t willing to do so and threatened to show her letters to her fiancé.

Seemingly with no other solution, Madeleine poisoned her lover with arsenic, which she put in his cup of cocoa. She was tried in 1857 but acquitted as there was a lack of evidence due to the fact that the dates on the letters were missing and nothing could be proven. After the scandal, Madeleine left Scotland and moved to London, where she married an artist, George Wardle, and they had two children together.

Mary Ann Cotton

One poisoner found guilty was Mary Ann Cotton, born in 1832 in England. She was hanged in 1873 for the murder of her stepson, Charles Edward Cotton. She may have, in fact, killed 21 people in total, among whom were three of her four husbands, 11 of her 13 children, and her mother. The poison she used was arsenic, which causes gastric pain and rapid decline of health.

In 1852, Cotton married her first husband, William Mowbray, when she was 20. Mowbray was a miner, and she had four children with him. He went to sea to work as a stoker and, during one of his visits home in 1865, he died suddenly of an intestinal disorder, along with two of his children, leaving Mary a widow.

Cotton started working in Sunderland Infirmary as a nurse, where she met her second husband, George Ward. He was an engineer and a patient in the hospital at the time. They got married in 1865, the same year that Cotton’s first husband died, but their marriage didn’t last long. Ward died after a year, in 1866, after a long illness characterized by paralysis and intestinal problems.

His widow didn’t grieve too much. She collected the insurance money and married James Robinson in 1867. A widower himself, Robinson had four children from his previous marriage. In just one week in April, two of his children, along with one of Cotton’s daughters, died of intestinal problems. A week before their death, Cotton visited her mother, who died only nine days after the onset of, you guessed it, intestinal problems. Cotton was collecting insurance money for her deceased children when Robinson grew suspicious of her behavior and threw her out on the street.

However, her friend Margaret Cotton introduced Mary Ann to her brother, Frederick, whom she married in 1870. A year after she gave birth to their son, she learned that Joseph Nattrass, her former lover, was living nearby, and she reignited a romance with him. That same year, her husband, Frederick, died from “gastric fever” and Mary Ann Cotton collected the insurance money.

Of course, her lover died of the same “illness,” as well as her next lover, and her next baby, until 1873, when the local doctor, Dr. Kilburn, became suspicious after her stepson died, and Mary was brought to Durham Assizes. She was hanged at Durham Jail.

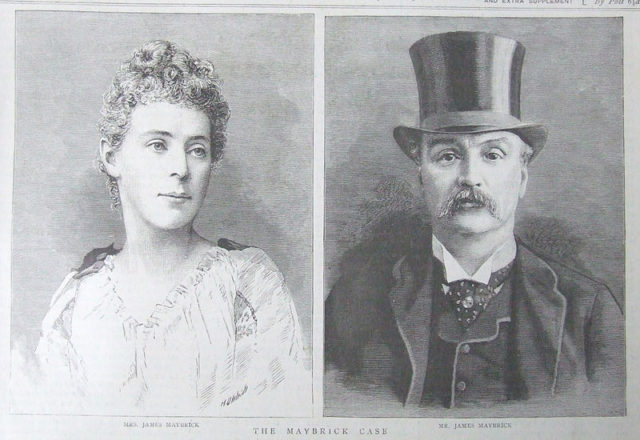

Florence Elizabeth Maybrick

Florence Elizabeth Maybrick, an American, in 1881 was married to James Maybrick, a British cotton broker. She was 19 and he was 23 years her senior. It was said that they seemed like a happy couple, always smiling and holding hands at parties, but the reality was different. Maybrick had a lot of mistresses, and his wife started a few affairs of her own. She was also accused of having a romance with one of James’ brothers, Edwin.

But the affair that caused the most speculation was her relationship with Alfred Brierley, a local businessman. After her husband found out about them, he asked for a divorce, which was apparently something that they both wanted. However, in April 1889, Florence bought flypaper containing arsenic and she soaked it in a bowl of water.

Related story from us: Victorian fashion: Restrictive, uncomfortable, and a little dangerous

The autopsy of Maybrick’s body revealed arsenic in his stomach and the packet was found on which was written “Arsenic. Poison for rats.” The accusations fell on Florence. She was arrested and at first sentenced to death but later given life imprisonment. After serving 15 years, she was released in 1904.