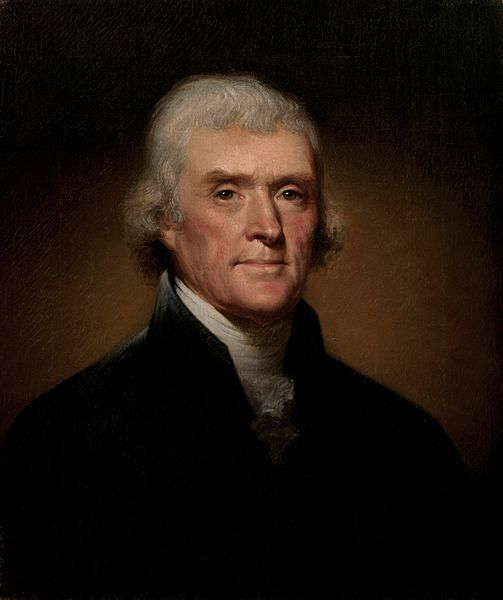

Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, one of the Founding Fathers of America, the organizer of the Louisiana Purchase, and the third president of the United States … need one go on when discussing his legacy? The answer is yes. The legendary Jefferson also stands out for his contribution to the field of gastronomy. The man knew about tasty food.

American cuisine in the 18th century was of course highly influenced by the English, containing meat, vegetables, and pastries accompanied by beverages such as ale, Madeira port wine, or hard cider. The methods for meat and vegetable preparation included boiling, stewing, or baking while the breads and sweet pies were baked.

Due to his professional position of minister plenipotentiary, Thomas Jefferson had the good fortune to travel around Europe and experience the different cultures, and one of the essential features of their identity was gastronomy and cuisine. In 1784, he set off for France, visiting Paris and the southern regions of the country, as well as northern Italy; this voyage developed in him an everlasting appreciation of fine cuisine. He was so thrilled by French cooking that he arranged for one of his slaves to learn and master the skills from the country’s renowned chefs. Soon, he got himself a chef de cuisine who cooked for him in his private residence on the Champs-Elysees.

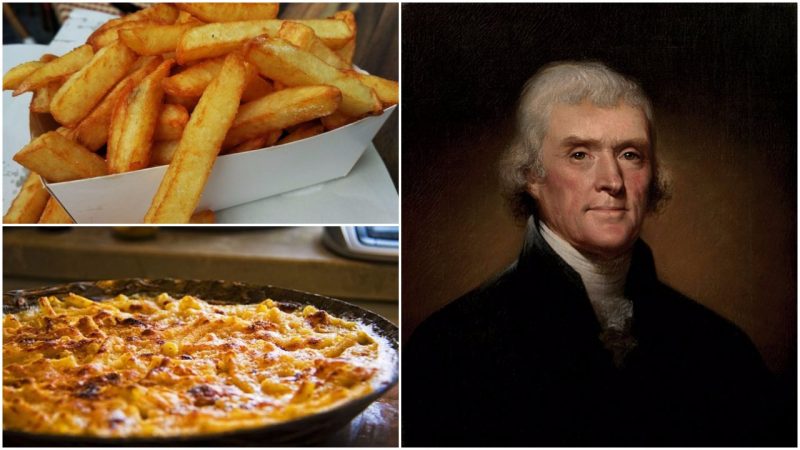

While he was touring and savoring various delicacies, Jefferson diligently noted all the skills, methods, tools, and utensils for cooking that he wanted to bring home to America. One such observation included the macaroni that he found in Italy. He was so enamored with the pasta that he sketched a “macaroni machine,” and in 1802, at a state dinner in his home in Monticello, in Virginia, he served the macaroni with some cheese, making the dish the talk of the town–and one of today’s most popular dishes.

Alongside mac and cheese, Italy introduced Jefferson to another indulgence: the irresistible gelato or ice cream. He enjoyed it so much that by 1796 he created “freising molds” to ease its production and collected different recipes. As president, he served ice cream at formal dinners, spoiling the guests who were puzzled by the flavor and texture of the new dessert. One of the guests, a congressman from Massachusetts, wrote, “Ice cream very good, crust wholly dried, crumbled into thin flakes,” to which the Representative Samuel Latham Mitchill added, “Balls of frozen material inclosed [sic] in covers of warm pastry, exhibiting a curious contrast, as if the ice had just been taken from the oven.” The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. has a handwritten recipe of vanilla ice cream written by Jefferson himself.

Karen Hess, a food historian, has brought up the possibility of Jefferson being the initiator of America’s romance with French fries. Reportedly, Jefferson first served them at a lavish party at the president’s house. He brought back the recipe from France, so the chef and the maitre d’hotel acquired a new way of preparing potato slices, cutting them in small round pieces and frying them raw.

France is once again to blame for another of Jefferson’s delicacies, wine and, in particular, champagne. Back in 1789, on his return back home from France, he brought along 680 bottles of wine. In addition, he attempted to plant various grape varieties but never succeeded. However, his knowledge of enology was highly recognized in America, earning him a reputation as a real wine connoisseur.

At most of his formal dinners the finest imported champagne was served and Jefferson, an avid fan, was so fond of the it that he reportedly kept a corkscrew next to the toothbrush in his carrying case. He preferred a flat champagne, considering the sparkling type to be a “silly fad.”

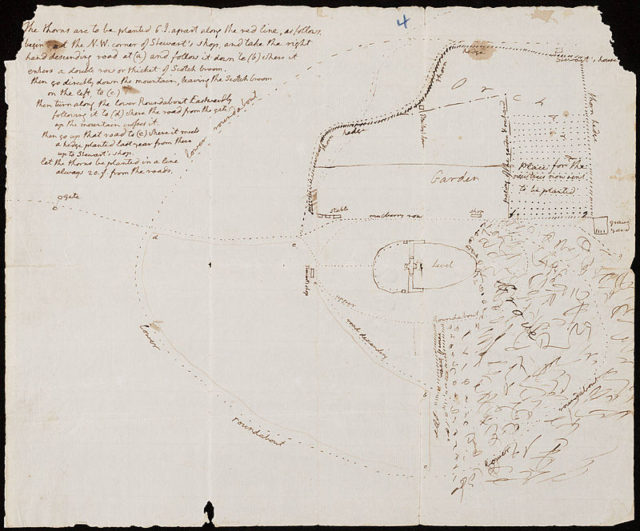

His passion for cooking didn’t stop there. At Monticello, he created an experimental kitchen garden and vineyard, where he cultivated 330 varieties of 89 species of vegetables and herbs as well as 170 varieties of fruits.

In his “Garden Book,” a horticultural diary he wrote after his retirement, recording his achievements and failures, he noted:

Read another story from us: Thomas Jefferson had a pet sheep, which killed a small boy

“I am constantly in my garden or farm, as exclusively employed out of doors as I was within doors when at Washington, and I find myself infinitely happier in my new mode of life.”