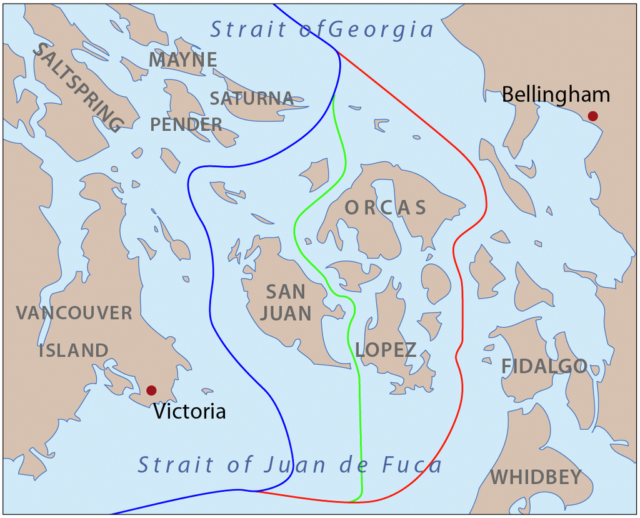

In 1845, when the Oregon Treaty was signed between the United States and the United Kingdom, it seemed that an end had been brought to the Oregon boundary dispute that had caused controversy for years. With a compromise proposal, the boundary to finally settle territorial claims on the area was set through the San Juan Channel, a division that remains to this day.

At that time the only maps of the area were imprecise, so setting a border through the channel was not so easy when it came to the San Juan Islands. Sitting as they do between Vancouver Island in the British Columbia province of Canada and Washington State in the U.S., the channel splits into two straits, the Haro Strait to the west and the Rosario Strait to the east.

The wording of the treaty, that the borderline should be set in the middle of channel, was therefore ambiguous. Both the United States and Britain claimed sovereignty of the archipelago because of its strategic positioning.

Civilians of both nationalities were encouraged by their governments to settle on the island. The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), based at Fort Victoria, established salmon-curing stations on the western shoreline of San Juan Island in 1851. The U.S. government answered with the creation of the Washington Territory in 1853, when the island was included in their possessions. A few months later, to prove that the island is British, the HBC founded the sheep farm Belle Vue on the southern shore of the island, after which 20 to 30 U.S. settlers moved to the island.

However, despite the political game played by both governments, according to reports both the British and the American settlers on the island had a peaceful time without any disputes. At least not until 1859, when the bloodless “Pig War” began.

The war was started when an American farmer by the name of Lyman Cutlar found a large black pig eating the potatoes in his garden. He got very angry and in a fit of rage killed the pig. The owner of the pig was an Irishman named Charles Griffin who was known to let his pigs roam freely. He was also an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Even though neither of the two men involved in the pig conflict had been known to cause problems, they were the ones who initiated a war. At first, feeling guilty, Cutlar offered $10 to Griffin as compensation for the pig, but his offer was refused.

Griffin was angry and asked Cutlar for $100. While one man was complaining that the pig was eating his potatoes, the other believed that the owner should have kept his garden from the pig. So, as little children solve big dramas, both sides turned to their authorities for help.

At first, Griffin reported Cutlar to the local British authorities, who threatened to arrest the American farmer. Cutlar then called for protection to the U.S. military. The petition for help was received by the commander of the Department of Oregon, Brigadier General William S. Harney, who had strong and well-known anti-British views.

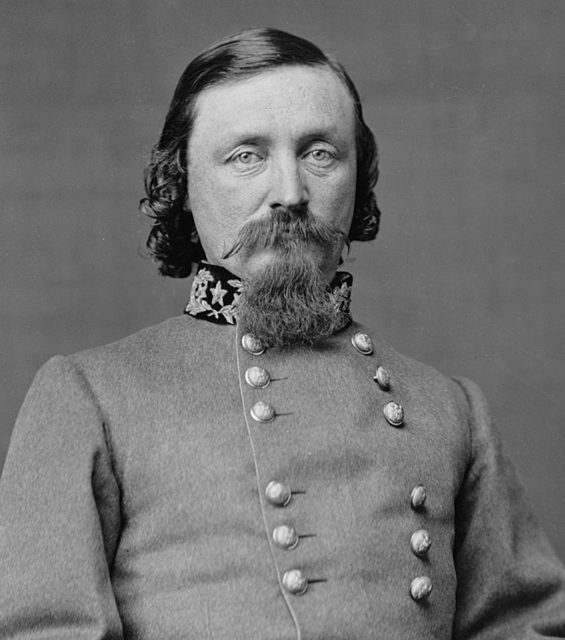

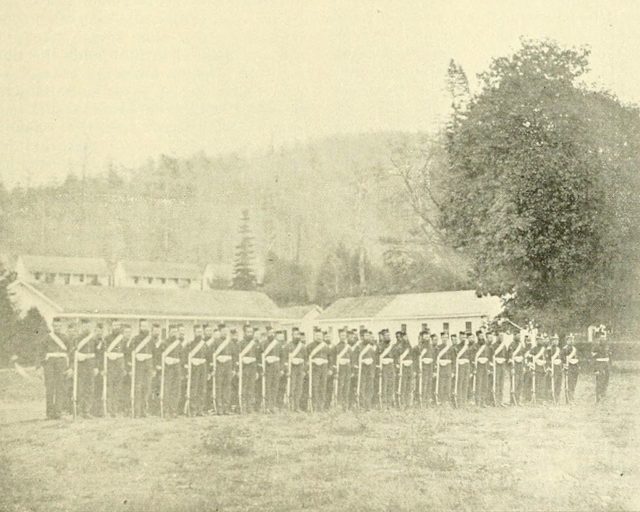

Without any hesitation, he sent 66 American soldiers under the command of Captain George Pickett to San Juan Island on the 27th of July, 1859. When the governor of British Columbia at the time, James Douglas, heard about the American military on the island, he sent three British warships to San Juan.

During the following month, without any shots fired, the military presence on both sides on the island steadily grew. By August 10, there were 461 American and 2,140 British men.

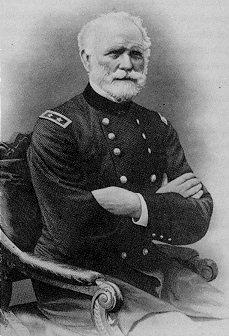

Governor Douglas ordered the recently arrived Admiral Robert L. Baynes, Commander-in-Chief of the British Navy in the Pacific, to engage the American soldiers. But Baynes refused, famously saying that he wouldn’t “involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig.”

When word about what was happening on the island reached London and Washington, D.C., officials were startled, and both sides decided to put an end to the escalating crisis before it was too late. After a set of negotiations, the U.S. and Britain said that until a formal agreement could be found, there should be no more than 100 men from both nations living on the island. The British settled in the north and the Americans in the south of San Juan, and they lived as such for the following 13 years.

In 1872, the dispute over the possession of the island was finally settled by an international arbitration led by Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany. It was decided that the island entirely belonged under American control, and it so remains. The British and American camps are today part of the San Juan Island National Historical Park, which is the only national park on U.S. soil where a foreign flag is regularly hoisted.