Recently Iceland abolished a 400-year-old local law of West Fjords calling for all Spaniards from the Basque region to be killed on sight. This law has somehow managed to survive for four centuries, even though thankfully it was not widely applied.

The law springs from a shipwreck leaving a group of survivors from the Basque country stranded in Iceland. Desperate sailors resorted to petty theft in order to gather food, and that met with a harsh response from the locals.

But what were these Spaniards doing so far away from home?

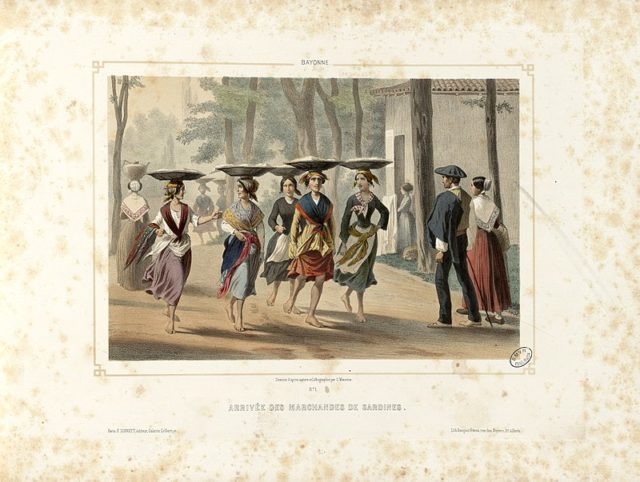

In the 16th century, seamen from the Basque country were running a large-scale whale-hunting venture based in Labrador and Newfoundland, in what later became Canada. The Basque whaling fleet consisted of more than 30 ships carrying 2,000 men, all involved in this lucrative business. They were the first to exploit whale hunting commercially.

During the 1560s and 1570s, the Basque whalers hunted down more than 400 whales per year. This was their “golden age,”a period in which there was no match for the sailors of the Basque country.

Many others sought instruction from the Basques, as they too were interested in mastering this difficult and dangerous craft. Jonas Poole, an English explorer and adventurer, often spoke of the Basque and their special trade “for [they] were then the only people who understood whaling.”

Iceland relies heavily on fishing to this day, and it was usual for the Basque whaler fleet to hunt around the small island in the Atlantic. The region was home to a large habitat of Right and Bowhead whales, which were nearly extinct due to the tireless hunting of that period. Whaling was quickly becoming one of the most prominent branches of the economy of Europe, as well as of the New World.

In 1615, a detachment of the Basque fishing fleet consisting of three ships was stationed in Iceland. The locals shared benefits from the whaling operation with the Basques, which led to a mutual agreement that was respected at first.

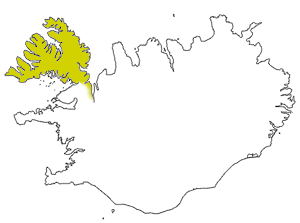

When the departure time came in late September, a maelstrom occurred, blowing back the ships and crushed them into the unforgiving fjords. Luckily for the Basque crew, most of them managed to survive the shipwreck and reach the safety of shore. Approximately 80 sailors under the command of captains Pedro de Aguirre and Esteban de Telleria were stranded and forced to spend their winter in the unforgiving landscapes of the West Fjords.

But the harsh weather was not the only challenge. Food supplies were scarce, and the stranded sailors started harassing the local population. They resorted to banditry on several occasions.

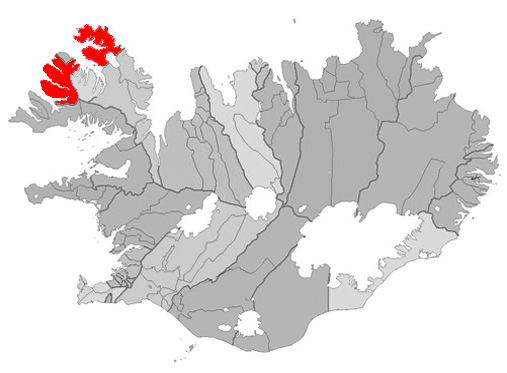

The spark that ignited the conflict between the Icelanders and the Basque occurred in the village of Thingeyri, which is one of the most northern points of the island. A group of sailors broke into an empty house and stole some dried fish.

CC BY-SA 3.0

After this theft, the locals became infuriated, and the unwanted visitors received a cruel vengeance. On the night of October the 5th, 14 of the Basque seamen were murdered while sleeping. Among them was one of the captains, called Martín de Villafranca of San Sebastián. Only one young man named Garcia managed to escape the bloodbath. The bodies were disposed of in the ocean.

An Icelandic poet and alleged sorcerer, Jón lærði Guðmundsson, later wrote of the incident, noting that the sailors were “dishonored and sunken into the sea as if they were the worst pagans and not innocent Christians.” He criticized the violence toward the Basques by writing A True Account of Spanish Men’s Shipwrecks and Slayings, in which he took their side by saying that the sailors were unjustly killed.

Three days after the massacre, the local sheriff, Ari Magnusson, declared all Basques as outlaws, calling for them to be killed on sight. Two more cases were registered, one in 1615, and the other in 1616, when the law was enforced, resulting in the death sentence of two more lingering members of the Basque fleet.

These accounts are considered the worst massacres in Icelandic history. The law applied only to the region of West Fjords, so it comes as no surprise that it was completely forgotten, as it became irrelevant.

After numerous reforms over the next four centuries, this bizarre directive was finally abolished. Concerning the issue, nowadays West Fjord’s district commissioner, Jonas Gudmundsson, stated: “We have laws, of course, and killing anyone—including Basques—is forbidden these days.”

A symbolic reconciliation ceremony was organized by the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery, where the law was officially abolished. In it, the descendant of one of the Basque victims, Xabier Irujo, shook hands with the descendant of one of the men who participated in the massacre, called Magnus Rafnsson.

This act was indeed symbolic, as Spain and Iceland hold no grudge toward one another concerning the 17th-century incident, but it was nevertheless an act correcting one of the history’s mistakes.