There is a peculiar witticism generally employed to describe a salesperson’s ability to sell virtually anything to anyone: “Like coals to Newcastle.” What is not widely known is that there was an 18th-century entrepreneur from Boston, Massachusetts, who did send a large quantity of coal to Newcastle, a massive mining city in England. Moreover, he was a man so desperate for attention, he was willing to fake his own death.

Born in the winter of 1748 to a family of colonial farmers who struggled to make ends meet, Timothy Dexter was determined to make a name for himself. And in the end, he did–not through diligent efforts, nor through education, but by sheer luck and a sense of timing.

He never finished school, dropping out at the age of eight to help his parents on the farm. This went for about six years, until he left home to learn a trade. He stayed in Boston for seven years, working as an apprentice to a leather dresser. Dexter learned his craft and moved on. He sought to make his name known by starting a business and being a leather dresser himself. With no home nor immediate prospects, on the eve of the Boston Tea Party, Dexter met a woman instead.

Elizabeth Frothingham was older, a widow to a former associate of his, and a mother to four. She had money and an established leather shop that her deceased husband left behind. Soon enough they married and moved to her large estate in Boston.

There he worked for a while and saved a few bucks. But his wealthy neighbors, such as John Hancock, had much more than a few. Wanting to be equal to someone like Hancock and more than a leather stretcher, he asked around most persistently for an investment opportunity. The snobbish elites of Boston supposedly perceived him as an illiterate fraud and so, in an effort to bankrupt him, they persuaded Dexter to invest everything in the Continental dollar bills that were issued recently.

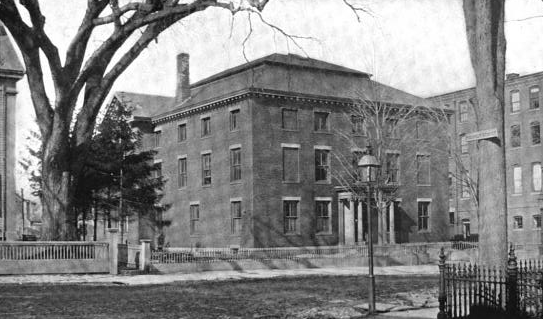

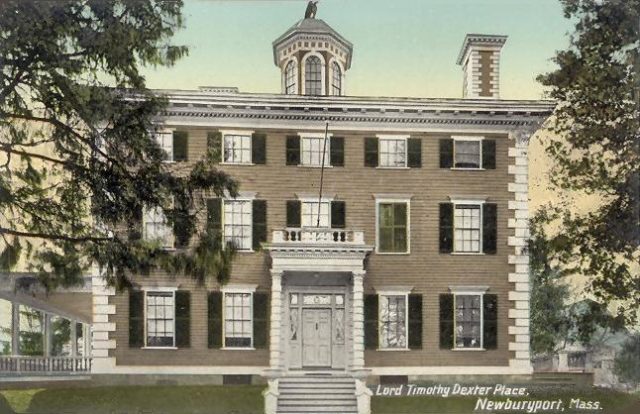

In complete naivety, he gathered all his savings as well as his wife’s and bought this new currency. At first it seemed worthless. But by the end of the American Revolution, the new currency had risen significantly in value and made him a millionaire, allowing him to obtain a mansion-like house in the middle of Newburyport, that is now part of the town’s public library.

Irritated by his success and his crude and intrusive nature, the same neighbors are said to have proceeded to give him bad advice on purpose, pushing him toward risky and apparent idiotic ventures. Dexter took all the recommendations without reservation. And against all the odds, he somehow came out on top time after time, making a huge profit out of their “excellent” advice.

“Why don’t you send bed-warming pans to the Caribbean islands” one would suggest. “And while you are at it, why don’t you ship them a bunch of cats” another one would continue, jokingly. And as it happened, while this tropical place was in no need of warming whatsoever, they were in need of ladles, pans, and pots, so they were sold as such to the sugar plantations owners. As for the cats, the stray cats he had gathered from the city streets, he sold every single one along with more than 40,000 of the pans, for their fields were rat infested and they came in handy at the right time. And for a costly price.

This trend went on for years and escalated to the extent that his neighbors, now fed up and angry, even suggested, “Why don’t you try selling coal in Newcastle, they are in great demand,” clearly taunting him for his ignorance, for everyone was well aware that Newcastle was the largest mining center in England, one from which even Boston was importing. However, Dexter didn’t know this, so he did send coal supplies to the city. Another thing that no one was aware of was that, while his shipment was traveling across the Atlantic, the miners went on strike and his delivery was more than welcome and sold at high price.

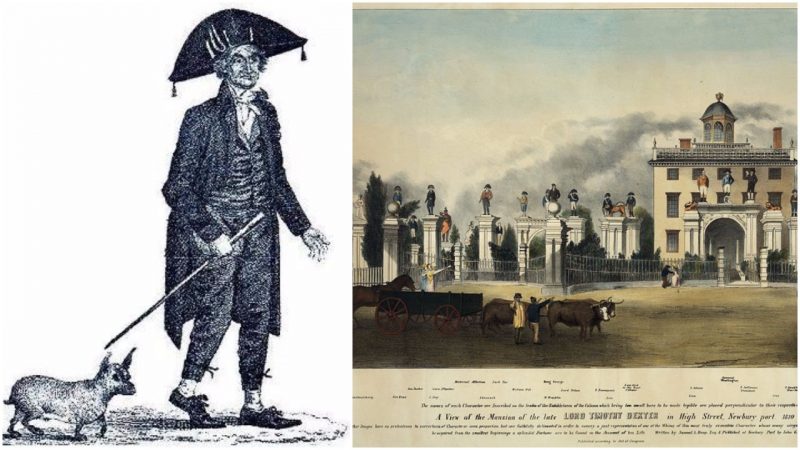

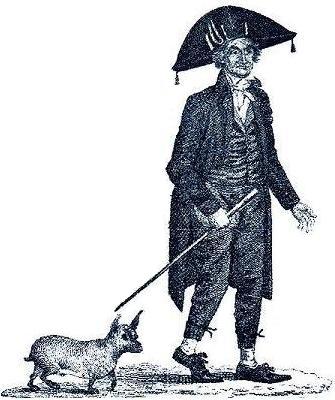

But as much as he tried to be a success in his endeavors, people still found his presence appalling and viewed him as a distasteful buffoon. He bought a massive estate in Newburyport and raised a lavish chateau with a clear view over the sea and decorated it in a tasteless manner with 40 and more statues erected in the front yard including one of himself under which it was written: “I am the first in the East, the first in the West, and the greatest philosopher in the Western world.” This coming from a man who also raised a statue of Thomas Jefferson alongside his, with “Constitution of Independence” engraved underneath.

Despite America fighting a revolution to do away with royalty and titles, he announced that he ought to be considered a “Lord” from now on. He eventually gained a few friends here and there, but he suspected they were in it only for the money. So in his last attempt to test his worth, he staged his own funeral ceremony and forced his wife and children to take part, giving them clear instructions on how to behave during the service. And that service was a grand one. More than 3,000 people came, many of them only out of curiosity. They found him alive right after the ceremony, beating his wife with a cane in their kitchen for not crying enough. Instead of mourning him, he found her laughing with the guests.

“Lord Dexter” passed away shortly after his fake funeral at the age of 59, on October 26, 1806. But before he did, he published a book, A Pickle for the Knowing Ones, or Plain Truths in a Homespun Dress, which sold in eight editions, although at first he gave it for free, as a memoir, for people to remember him by. It goes something like this: “IME the first Lord in the younited States of A mericary Now of Newburyport it is the voise of the people and I cant Help it and so Let it goue.” By the end of it, it is hard to tell if he was a legendary entrepreneur who played an elaborate trick over the elite, or an illiterate yet extremely fortunate jester.