In the small town of Holmavik, located on the western coast of Iceland, there is a museum dedicated to preserving the world of magic and sorcery. The Strandagaldur, also known as the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft, started out as a small but enthusiastic project from its original curator, Sigurður Atlason, and ended up as a popular tourist attraction.

A caped skeleton reaches out while bursting through the stone floor, welcoming guests and setting the haunting tone of a past world filled with incomprehensible recipes for over-riding your troubles. So, if you are interested in making yourself invisible, obtaining an infinite source of money, or just getting really good at fishing, this place is right for you, offering spells for each of these fortunes.

The Strandagaldur gives a unique insight into an age dominated by superstition and magic. When the heritage of a polytheistic religion clashed with the notion of Christianity, the byproduct arose in the form of sorcery. It was present in everyday life, since it was an instrument by which a person could influence their destiny, foresee it, or perhaps even shape it.

Christianity became an official religion in Iceland in 1000 AD, but a developed pagan culture had already put down deep roots in Icelandic society. It was something of a bond with Iceland’s former motherland in Scandinavia.

Therefore, pagan sorcery accepted the authority of the Christian church and even attempted to “misuse” it for personal gain. For example, a spell for producing a tilberi includes stealing sanctified wine from three consecutive Sunday communions. A tilberi, for all those not acquainted with Icelandic folklore, is a demon summoned by a witch, with the sole purpose of stealing milk from neighbors.

Even though this type of witchcraft sounds almost harmless, there is a macabre twist in Icelandic sorcery. One of the main exhibits, which is a replica and is certainly the one that causes the most disgust, is the Nábrók. These can be translated as the “necropants,” trousers made of human skin meant to supply the wearer with an endless source of wealth and fortune.

Now, putting the gore aside, this does have a tempting promise. The spell includes a Stave, which is an Icelandic system of magical songs, permission from the person whose skin was used after his death, and a coin stolen from a poor widow.

In order for the person wearing the pants and exploiting the spell to avoid eternal punishment in the afterlife, he is required to give his Nábrók to someone else before he dies.

Even though there is not sufficient evidence of someone actually producing the necropants, this strange and dark piece of folklore is captivating, even more so since a very realistic replica was made for the purpose of the Museum.

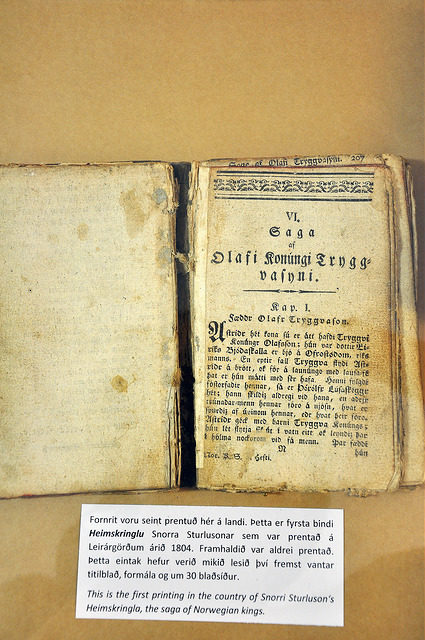

Other exhibits include occult books, scrolls, and records of witchcraft and magic, mostly dating from the 17th century, when a bulk of the Staves were first documented in various spell books, or grimoires, as they were called.

Decorated rather spookily, the Museum is somewhere between a horror show and a site of historic value. Perhaps that is why it is so popular among tourists who happen to visit the region of Westfjords.

Opposition initially arose among the more conservative locals, as the scenery of the museum was considered to be too macabre for the community.

As the small coastal town began to experience the benefits of such an attraction, all opposition disappeared. The Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft was opened in 2000, running consistently for 17 years, and it continues to draw the attention of visitors while exploring and demystifying the long and forgotten tradition of Icelandic sorcery.