Ancient civilizations put tremendous effort and resources into preparing for the afterlife, particularly those of power and wealth. Anyone with cursory knowledge of ancient Egypt is aware that these people dedicated the greater portions of their lives to preparing for death.

The pyramids, the eternal homes of the great Egyptian pharaohs, took decades to build. The huge quantities of funerary items were often of considerable cost, from expensive coffins to jewelry, gold, and other offerings that would equip the tomb.

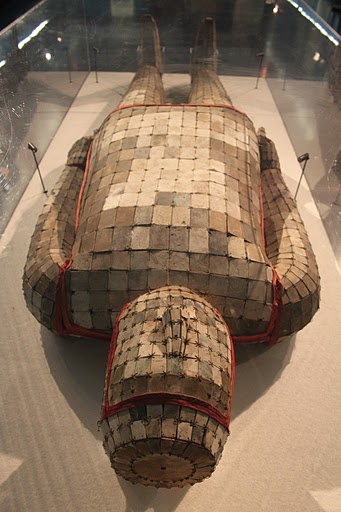

It was no different in other corners of the world. The Chinese, for example, made jade burial suits for the imperial family, elaborate afterlife armors created from pieces of jade that were held together by gold or silver wire thread. The ancient Chinese produced these lavish costumes because they believed that the great power held by the gem would guarantee immortality to the wearer as well as keep evil forces away.

Of course, the bodies of the deceased diminished over time, and the jade suits protected nothing but bones inside. As the production of jade suits ceased at some point during ancient Chinese history, people slowly started believing that such suits were mythological.

Historical accounts and texts from as early as 320 AD describe the existence of the jade suits, but it took centuries before any were found. Finally, in 1968, researchers discovered the first two examples, and headlines were full of it all over China. Shortly after, the find was dubbed one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the century.

It was determined that the jade suits belonged to Prince Liu Sheng and his spouse, Princess Dou Won. They had once been part of China’s most prolific dynasty, the Han family, who reigned between 206 BC and 220 AD. Their long-forgotten tomb was located in the Chinese province of Hebei, in a heavily secluded area, blocked by a wall made of iron. These two royal costumes are now exhibited at the Hebei Province museum.

Both were composed of more than 2,000 jade plates. The suit belonging to the prince was threaded with gold, while silver was used for that of the princess. Less than 20 other such jade suits have been discovered since the 1968 groundbreaking discovery. The reason why there were so few? These suits took extensive amounts of efforts to produce.

It is estimated that the most gifted craftsman of jade would have needed at least a decade to create a single one. Another reason: criminals knew the value of the costumes, and many ancient tombs across the globe have been broken into to plunder the valuable grave goods.

Not all suits discovered had been threaded with gold and silver, though. It depended on the position the deceased had in society. Naturally, the golden thread in sewing a jade suit was reserved only for the great emperors of the nation. Silver was dedicated to close family members of the rulers, like their sons or daughters. Copper or silk thread was allowed for suits produced for aristocrats of lesser ranks.

The ancient Chinese craftsmen employed specific techniques to attach the precious stones by wire and produce larger shapes with a single group of gems in order to manufacture these invaluable afterlife assets.

Sets of instructions and criteria of how a jade suit should be produced have been discovered in the Book of Later Han, though a thorough examination of some of the existent suit examples has shown that not all rules were obeyed. The quality of different jade suits produced varies widely.

One of the most expensive suits ever found was that of Prince Huai, made of 1,203 pieces of jade with a striking amount of gold: 2,580 grams of golden thread embedded. In another, 2498 jade plates were counted. Both these suits were found during the 1980s.

No matter how sophisticated the suit was, it always made for a compelling piece. It was due to not only the way the gemstones were arranged together but also their shape–sometimes square, other times rectangular. It is fascinating, to say the least. Slightly less common were the suits that took trapezoid or rhomboid shapes of jade plates.

The jade suits were a privilege only for the wealthiest in society. People who lacked high status were not allowed such a burial.