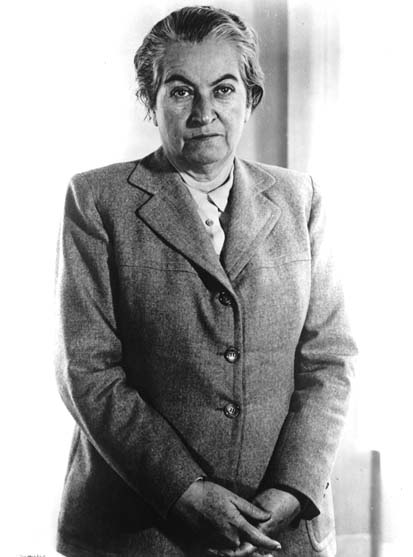

Gabriela Mistral vividly illustrated the lives of the poor, abandoned, and everyone who was in an unenviable position. In her words, one can hear the voice of thirst in a jealous lover, while in another, the loneliness of an abandoned woman.

Mistral’s writing also carries her voice, passionate about the freedoms of democracy during times of political dictatorships, and hers was always a voice that defended the politically and economically weak through her poems–women, children, Native Americans, poor people, workers, and war victims. They all found a place in Mistral’s poetry, or in her articles, and later in her speeches and actions when she worked in international organizations as a Chilean representative.

Although she openly wrote about everything that excited her, including friendships, relationships, politics, and marginalized groups of people who were mistreated, Mistral kept her emotional world a secret, and for many years, other authors tried to dig into the truth through her writings. But ultimately, they could derive only speculations about this introverted writer.

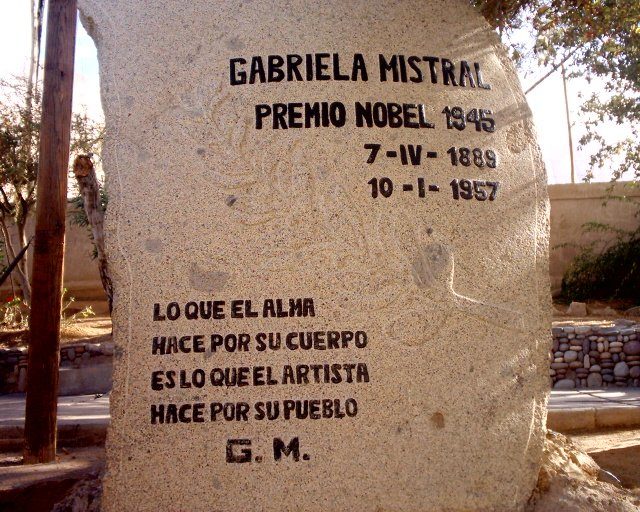

What is known is that her life was followed by misfortune. She was born Lucila Godoy Alcayaga in the village of Vicuna, Chile, in 1889. Her father abandoned the family when she was three years old, after which Gabriela moved to the Andean village of Montegrande with her mother and sister. Unfortunately, her mother’s health was fragile, which forced Gabriela to start working at the age of 15. However, since she was always dedicated to reading, studying, and writing, Gabriela found pleasure in taking a position as a teacher’s assistant.

When she was 17, Gabriela met a railroad worker, Romeo Ureta, and fell in love with him. After three years, Ureta committed suicide. His death left a lifelong mark on Mistral’s life and her writings. And yet, the tragedies weren’t over. Later in her life, one of Mistral’s nephews also committed suicide.

Mistral dedicated her life to her career as a teacher and to her writing. She was already a known advocate for liberalizing education for women and all social classes. She had written many articles in the newspapers in which she opposed the educational system and the politics in all. Mistral had quite the right to speak out about the necessary changes in education, as she herself had lacked formal education in her adolescence due to her social status.

However, she was still capable of becoming a teacher, and she did so. Not only was she a devoted teacher, but Mistral was rapidly changing posts from one town to another, and them from one city to another. In 1918, she was appointed by the Minister of Education, Pedro Aguirre Cerda (later president of Chile), to direct a Liceo (a type of high school) in Punta Arenas. In 1921, Mistral took a post as a director of the recently opened and most prestigious Chilean school for girls in Santiago. However, after a year of controversies and speculation over her nomination, Mistral moved to Mexico, where she worked with José Vasconcelos, the Minister of Education on reforms for the schools and libraries in Mexico.

She spent two years in Mexico before traveling to the United States. Her poetry became internationally famous, and Mistral also traveled to Europe, where she continued writing. She was appointed a representative of Latin America at the League of Nations and later a representative in Madrid, Lisbon, and Naples. Mistral was awarded honorary degrees from universities of Florence and Guatemala. She became an honorary member of various cultural societies in Chile, Spain, Cuba, and the United States. She taught Spanish literature at the University of Puerto Rico, and in the U.S. at Vassar College, Middlebury College, and at Columbia University. Mistral was among the first who recognized the extraordinary talent of another famous Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda.

Unfortunately, while she was rising professionally, she suffered great pain in her personal life. Her nephew, Juan Miguel Godoy, whom she considered a son, committed a suicide at the age of 17. It happened in 1943 at the peak of World War II, which also profoundly affected the poet. She was doing well in her career and suffered quietly. In 1945, Mistral became the first Latin American to ever receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and only the fifth woman in history for that matter. Among the many honorary awards she was granted internationally, in 1951, Mistral was awarded the Chilean National Literature Prize.

Although busy with her appearances around the world, and writing poetry, Mistral always remained an advocate for the mistreated. She still cared profoundly and genuinely for marginalized people and mostly for the poor children. She remained a vocal advocate for the rights to education. Mistral died from pancreatic cancer in her home, in the town of Roslyn, New York, in 1957, at the age of 67. Her remains were transferred to Chile, where the government declared a national mourning for three days, during which hundreds of thousands of Chileans paid their respects.

Before her death, Mistral left everything that she possessed to the children from the villages in Valle del Elqui, including her birthplace, Vicuña, and the place where she grew up, Montegrande. She donated everything to the education of the children from these villages. Today, the whole area of Valle del Elqui is called the Route of Gabriela Mistral. There is almost no town in Chile where at least a street is not named after her, besides the numerous institutions and museums.