Some 214 years ago, the young United States made a business deal with France that helped the country double its size virtually overnight and without a single drop of blood. Using diplomatic skills, the U.S. managed to obtain an enormous piece of land known as the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon, who was in great need of money for an imminent war.

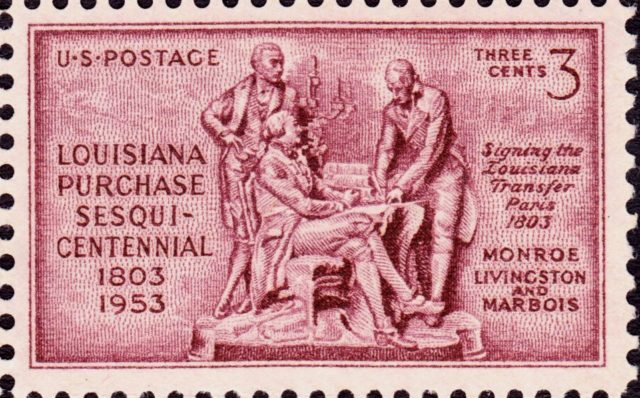

This territory, which stretches from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, became part of the 15 states that form today’s United States. For this development, the country has to thank the quick thinking of President Jefferson and the immediate actions of Robert Livingston, the United States ambassador to France at the time, as well as minister James Monroe, who was appointed by Jefferson to help Livingston in this matter.

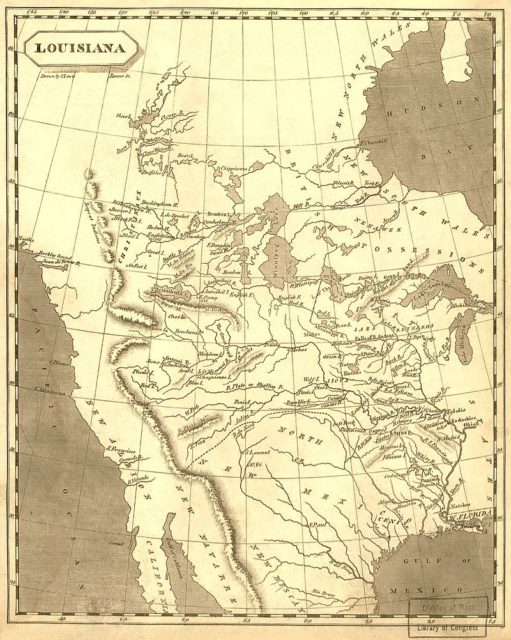

The territory of Louisiana was initially discovered by the Spanish Empire and these colonizers claimed the area that would later become Florida, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Then the French came, explored it, and started to bring settlers. The territory was ceded back to Spain in 1762. At the turn of the 19th century, Louisiana was to change ownership again.

At the beginning of the 1800s, Louisiana had around 60,000 colonists, some of whom were Creoles of French descent who lived a peaceful life that was in some ways aristocratic. Their eastern neighbors were different. The proud citizens of the United States, around 300,000 of them, were eager to explore, trade, and produce. These people who lived on the eastern shore of the Mississippi River depended on the export of goods that went through the port town of New Orleans.

They produced and exported goods such as tobacco, flour, whiskey, cheese, and butter. This important port town belonged to the Spanish Empire, and they had a trade deal with the United States government that allowed American ships to enter the port and take goods. Then came a development that was a huge blow to the fresh and frail economy of the United States.

Thomas Jefferson received some alarming information with the help of British spies. Napoleon, the war-hungry leader of Revolutionary France with ideas of expansion, managed to obtain the territory of Louisiana and with it, New Orleans, through a secret deal with the Spanish.

Jefferson, for the sake of his country, couldn’t allow New Orleans to be retaken by a foreign power. Soon, he authorized Robert Livingston, the U.S. ambassador to France, to begin negotiating a lease to the port of New Orleans. Napoleon and his foreign affairs minister, Talleyrand, then revealed the deal they had kept secret. Soon Napoleon announced his plan to make France a colonial power once again. Livingston was afraid of this. He sent a letter to Jefferson, explaining the situation and advising him to prepare the country for war. The angry American settlers, who were unable to send their goods for trade, were on edge, ready to fight, but Jefferson had a different idea, one in which his country would triumph.

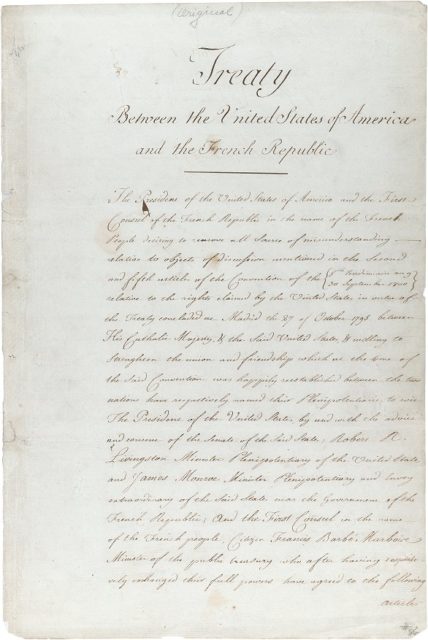

Although the President was aware that Napoleon’s deal with Spain strictly prohibited him from giving any parts of Louisiana to the U.S., he decided to try and buy New Orleans and the so-called “Floridas” in any way that he could. For this mission, he appointed minister James Monroe, who was immediately sent to Paris to help Livingston. At the same time, Napoleon had a plan of his own. He planned to sell Louisiana behind Spain’s back, without even informing his foreign affairs minister about the deal, or as he himself put it, “to commit Louisianicide.” The reason was his lack of money for his upcoming war with England. To make his decision even easier, he found out that the British had a huge fleet of ships waiting in the Gulf of Mexico to conquer Louisiana as soon as the war started. For Napoleon, Louisiana was a lost cause.

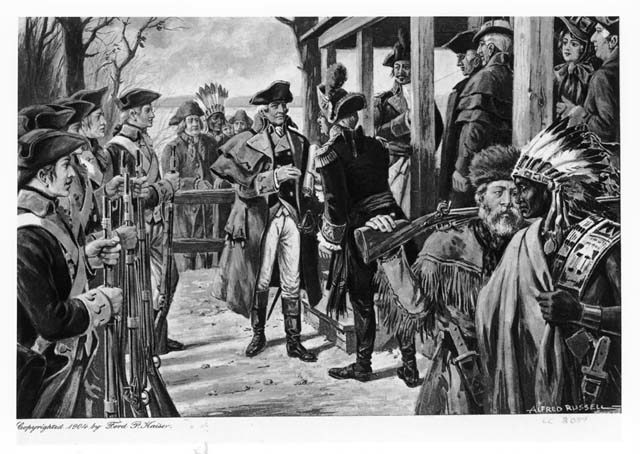

Monroe arrived in France, and by that time both sides were aware of their plans. One night, Barbe-Marbois, the minister of the treasury of Revolutionary France, came to Livingston’s house to a dinner party. The same night, at midnight, Livingston went to Barbe-Marbois’ office, where he received the offer for the Territory of Louisiana. Livingston immediately sent a letter to the president. Without even asking, the U.S. received an offer, and not only for New Orleans and the Floridas but the whole of Louisiana!

The initial price was very high, a sum that the still weak United States couldn’t obtain. Time was ticking by. Also, Livingston and Monroe were aware that it would take around 45 days for the letter to reach the president. They needed to make a decision on their own and make it quickly. After a few meetings, they managed to lower the price down to a somewhat acceptable $15 million. Realizing that this was the best offer, Monroe and Livingston decided not to wait anymore and accept the deal, without the permission of Jefferson, believing that he and the people of the United States would agree with them. On May 2, 1803, they shook hands with Barbe-Marbois, and the deal was made. It became official on May 22, four days after the war between France and England started.

When news about the bargain reached the United States, people were generally happy, but the biggest issue (even for Jefferson) was that the whole thing seemed unconstitutional. Nevertheless, the Senate agreed to endorse the purchase, and matters were set in motion. Because the country didn’t have the sufficient funds to buy this land alone, they needed to issue bonds and hope that somebody would accept them. The bonds were taken by a British investor, the banking house of Baring, and this here is where the irony comes in; the British financed Napoleon for the war against them.

This is how the United States doubled its size in a rare historical opportunity. On December 20, 1803, during a formal ceremony, the French flag in New Orleans was taken down, and in its place, the United States flag rose. Napoleon sold this rich, vast land for gunpowder and a pointless war.